Playlist

Show Playlist

Hide Playlist

Thoracic Surgery: Achalasia

-

Slides Achalasia Surgery.pdf

-

Download Lecture Overview

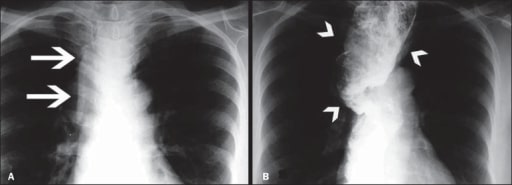

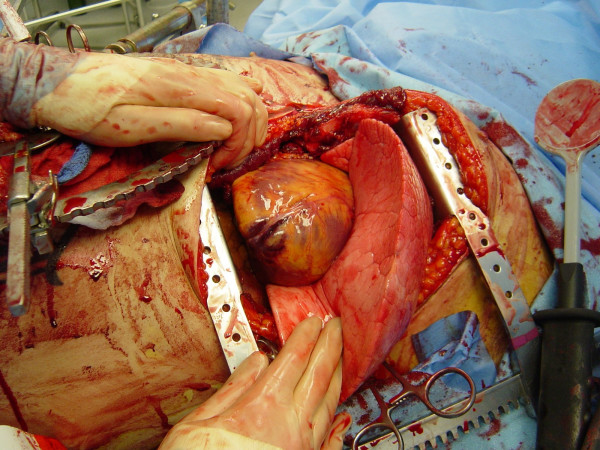

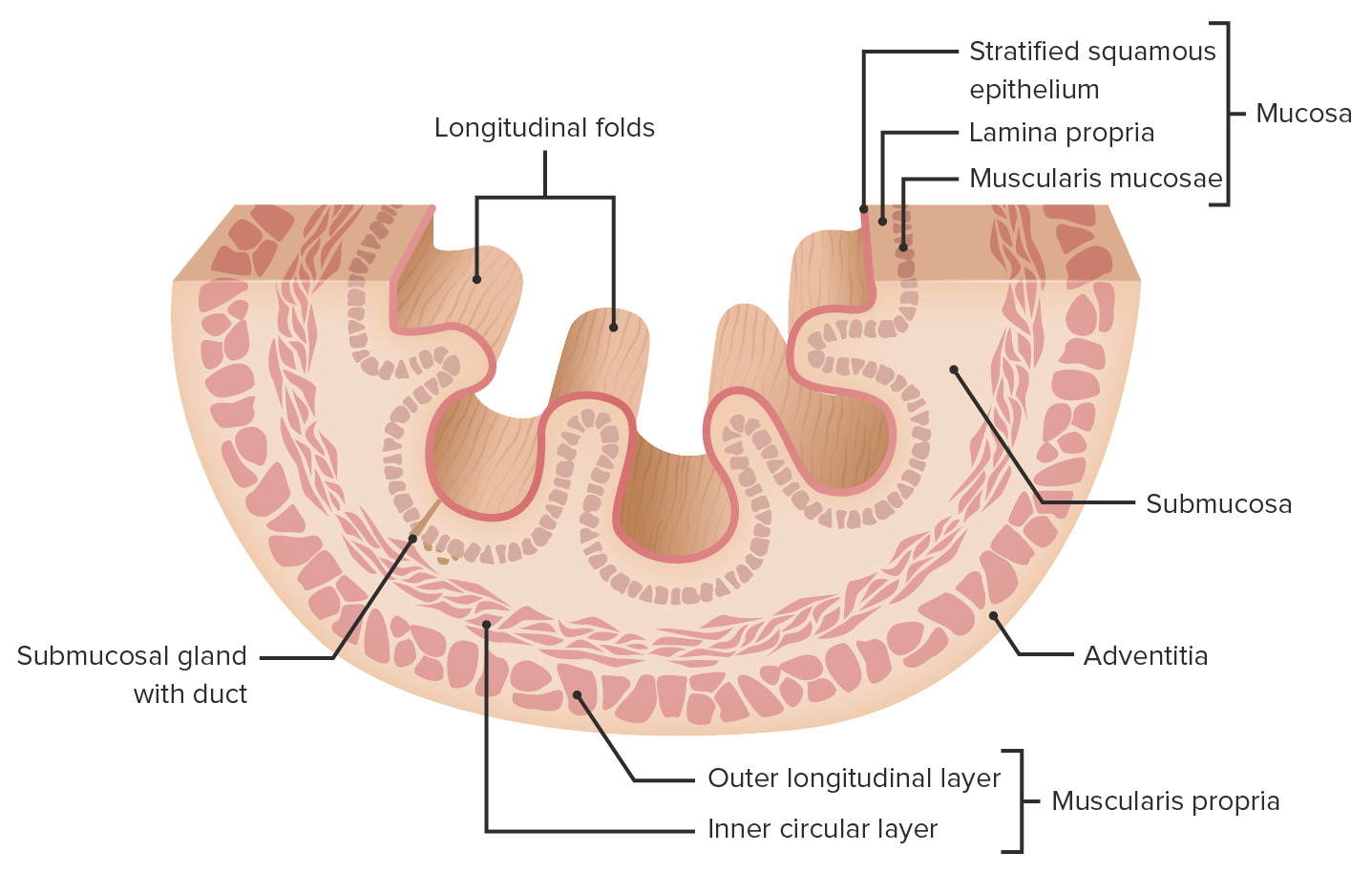

00:01 Thanks for joining me on this discussion of achalasia in the section of cardiothoracic surgery. 00:09 Here, you see a picture of a classic finding – we’ll get to it shortly – of an achalasia patient. 00:15 Do you notice what's wrong with this image? I'll give you a second to think about it. 00:22 Achalasia is described as a progressive degenerative disease of ganglion cells in the myenteric plexus of the esophageal wall. 00:32 Ganglion cells, as you know, in the myenteric plexus induce peristalsis. 00:38 So, if there is a destruction or degeneration of the myenteric plexus, peristalsis is affected. 00:47 The classic association to remember is Chaga’s disease. 00:52 In Chaga’s disease, infection with tropanosoma cruzi results in the loss of these ganglion cells. 00:59 Although, remember, not every patient has Chaga’s disease just because they have achalasia. 01:04 Now, what are some physical findings and historical facts? Patients generally complain of chronic dysphagia. 01:11 When it gets so bad, sometimes they even have a hard time tolerating their own saliva. 01:17 As a result of the decreased PO intake, because of the dysphasia, patients can have weight loss. 01:24 Sometimes, they also complain of atypical chest pain. 01:28 Remember, any time a patient presents with atypical chest pain, don't ignore it. 01:33 Consider it a possibility that the patient may be having a myocardial infarction. 01:38 Now, what about routine labs? Unfortunately, no routine labs is going to be very helpful in your diagnosis of achalasia. 01:46 And how would we diagnose it? Remember, the initial image that we showed on the introductory slide? Did you identify what was wrong? That’s right. 01:56 Take a look at the classic bird’s beak sign. 01:59 What you show here on this image is a dilated proximal esophagus. 02:04 This esophagus is approximately two or three times the normal size. 02:08 And this dilated esophagus tapers down to what's called the bird’s beak, just before entering the stomach. 02:15 This bird’s beak area is the approximate area of the lower esophageal sphincter. 02:21 Hallmark signs are defined by manometry. 02:24 All patients suspected of achalasia or any dysphasia, for that matter, should undergo some sort of a contrast swallowing study, oftentimes followed by manometry. 02:34 On manometry, you're likely to find failure of the lower esophageal sphincter to relax with swallowing. 02:42 That's a natural reflex. 02:44 Whenever you swallow for a meal, your lower esophageal sphincter relaxes. 02:50 And in addition, the other classic finding is aperistalsis of the esophagus. 02:55 Remember, those ganglion cells are damaged or degenerative, so no longer propagate peristalsis. 03:02 Here, you see a classic finding of a manometry. 03:05 Pay close attention to the bottom. 03:07 Notice the pressures on the lower esophageal sphincter. 03:10 It starts off quite high and never relaxes, despite the swallowing. 03:16 And additionally, you notice there's no amplitude changes depending on the length. 03:21 As you go from the top of the graph to the bottom of the graph, this is telling you where along the esophagus you are. 03:28 Generally speaking, the amplitude don't change significantly from the proximal to the distal esophagus, suggesting that there is no significant peristalsis. 03:37 Again, to remind you, classic findings of achalasia are: a failure to – a failure of the lower esophageal sphincter to relax upon swallowing and aperistalsis of the esophagus. 03:49 This sounds very similar to small bowel obstructions, doesn't it? When there's a distal obstruction, the proximal esophagus accommodates over time. 03:58 That's why you see the mega-esophaguses of achalasia. 04:03 Now, are there any medical treatments? Sure, there are. 04:06 And, in fact, if you're presented with a scenario with achalasia, try medical management before offering the patient surgery. 04:13 Patients undergo dilation and it’s actually quite successful. 04:17 Balloon dilation can be repeated multiple times with an EGD. 04:22 There is a downside with dilation, however. 04:24 With multiple attempts, dilation actually disrupts localized muscle. 04:29 As a result, more scarring can form. 04:33 Additionally, with repeated dilations, perforation can happen. 04:38 Be sure you warn your patients. 04:41 Next, botulinum toxin. 04:43 That's right. 04:44 Botox that you know from plastic surgery. 04:46 Botulinum toxin can actually release the hypertonic lower esophageal sphincter when injected. 04:53 This can also be done multiple times. 04:56 Unfortunately, in a subset of patients, medical management fails. 05:00 Therefore, patients need surgery. 05:03 Luckily, we have a very tried-and-true surgery. 05:05 It's called a myotomy. 05:07 Today, myotomies are largely performed laparoscopically. 05:10 But there's nothing wrong with the traditional open approach. 05:13 The goal of the myotomy is to incise or break the circular muscle of the esophagus. 05:19 When the muscle the esophagus is broken, the mucosa actually bulges through. 05:23 This muscle is carried both proximally and distally past the lower esophageal sphincter. 05:28 This allows the obstruction, if you will, to be relieved. 05:33 Remember, we have to incise both layers of the muscle to expose the esophageal mucosa. 05:38 That's how we know that it's gone deep enough. 05:41 Unfortunately, sometimes, despite being very careful, you could actually injure the mucosa. 05:46 That's important to remember and to counsel your patients. 05:49 As a result of incising these muscles, the mucosa is now unprotected. 05:54 Additionally, these patients may have severe reflux disease as a result. 05:59 For this reason, we perform what's called a partial wrap. 06:02 You may remember from our discussion of gastroesophageal reflux disease where a Nissen fundoplication is performed. 06:09 In that situation, it's a full wrap and not appropriate for the surgery. 06:14 Partial wrap the stomach around the esophagus will prevent reflex as well as protect your new myotomy. 06:22 This can be done with what's called a door or anterior fundoplication. 06:28 Here’s a door fundoplication in a laparoscopic view. 06:32 Door fundoplications is essentially using the floppy stomach and covering over your new mucosa that you’ve performed the myotomy. 06:42 Again, the fundoplication prevents reflex as well as protects your esophageal mucosa. 06:48 Now, it's time to review some important clinical information and high-yield facts. 06:54 Remember, trials of non-operative management are first-line therapies. 06:58 Don't be in a hurry to jump to the operating room when presented with this clinical scenario. 07:03 Do you remember what the non-operative management options are? I’ll give you a second to think about it. 07:08 That's right. 07:09 Botulinum toxin (or Botox) and dilations.

About the Lecture

The lecture Thoracic Surgery: Achalasia by Kevin Pei, MD is from the course Special Surgery. It contains the following chapters:

- Cardiothoracic Surgery – Achalasia

- Management of Achalasia

Included Quiz Questions

Chagas disease is associated with achalasia. Which of the following parasites causes this disease?

- Trypanosoma Cruzi

- Enterobius Vermicularis

- Cestoda

- Pseudoterranova

- Clonorchis Sinensis

Which of the following is NOT a treatment option for achalasia?

- Proton pump inhibitors

- Surgical myotomy

- Pneumatic dilation

- Botulinum toxin

Which of the following signs is seen on barium swallow in cases of achalasia?

- Bird beak sign

- String of beads sign

- Snowman sign

- Sandwich sign

- Shaggy esophagus

Customer reviews

5,0 of 5 stars

| 5 Stars |

|

5 |

| 4 Stars |

|

0 |

| 3 Stars |

|

0 |

| 2 Stars |

|

0 |

| 1 Star |

|

0 |