Playlist

Show Playlist

Hide Playlist

Seborrheic Dermatitis: Pathophysiology

-

Reference List Pathology.pdf

-

Slides Seborrheic Dermatitis Pathophysiology Dermatopathology.pdf

-

Download Lecture Overview

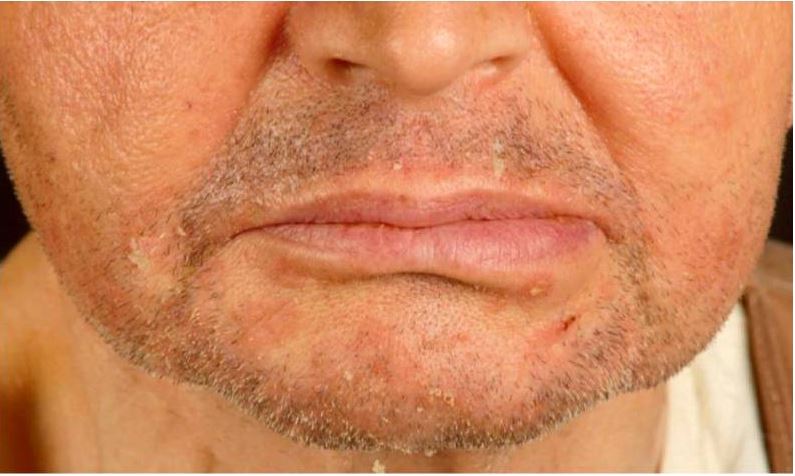

00:01 Welcome. With this talk, we're going to discuss a very common entity that probably affects all of us, even though we don't even realize it. 00:09 This is seborrheic dermatitis. 00:11 So seborrheic dermatitis is a common, chronic, relapsing papulosquamous, meaning there are little tiny papules and maybe little squamous plaques that are red and greasy with yellow scales. 00:25 Now that's on the skin. 00:27 And you may say, I've never had this. 00:29 You're right, you probably didn't. 00:31 But if any of you are watching and you've had dandruff, you've had seborrheic dermatitis of the scalp, and we'll come back to that. So it doesn't have to be in areas of the skin. 00:42 So the epidemiology. Really common. 00:44 3% of the general population, probably higher than that if we did a complete survey. Men greater than women, this probably has to do with the fact that men make more testosterone and therefore have more dihydrotestosterone, which affects the synthesis of the of the sebaceous gland products, the the greasy lipid deposition that comes out of the sebaceous glands. And as we're going to see, that's a major issue driving the pathophysiology of the disease. 01:13 There is a bimodal distribution. 01:15 The first peak is typically in infancy. 01:17 And most infants because of a kind of a naive immune response an immature immune response will have it that then goes away. 01:26 And the second peak will typically occur in adolescence and early adulthood, usually with the onset of puberty and the production of, again, more hormones that are going to affect the sebaceous gland. 01:37 Production of lipids. Up to 70% of infants will have it probably even more common than that, usually very early in life when they have a very immature immune system, typically will spontaneously improve all by itself by one year of life. 01:55 In adults, although the onset will typically be with puberty, the peak of incidence will occur in the third to fourth decades of life. 02:03 So the pathophysiology. 02:04 Let's understand this a little bit more. 02:06 So there is a normal skin microbiome that we all have. And it's a combination of bacteria and fungus and virus. 02:14 It's whatever's walking around in the world around us. 02:18 We have a normal kind of balance of the various entities that are there, and a normal balance of the immune response that kind of lives with it happily ever after, a commensal relationship. 02:30 However, if we change that microbiome, and particularly involving increased colonization with fungal species like Malassezia, then we can get into seborrheic dermatitis. 02:43 Once we have that fungal kind of super invasion or increased propensity in the microbiome, then we have the appropriate but then somewhat abnormal immune response to that altered microbiome. 02:58 And then as a result of that inflammatory response, the sebaceous glands are changed in terms of their proliferative capacity and what they are synthesizing. 03:08 And that gives us the full constellation of seborrheic dermatitis. 03:13 So let's look at this in a little bit more detail. 03:15 Here is our very happy microbiome with a balance of Malassezia and other microbes living very happily on the surface. 03:23 And everybody is in harmony. 03:25 The sebaceous glands, remember these are important adnexal structures of the hair shaft, are sitting there, and they are just creating a balanced amount of lipid that is coming out along the hair shaft and is lubricating the surface of the skin, is also preventing loss of water. 03:43 That's what those lipids are supposed to be doing. There is a small but nevertheless persistent inflammatory response. 03:50 The lymphocytes are there kind of surveilling the environment, and everybody is, as they say, in harmony and happy. 03:55 Now let's change that environment. 03:58 Now we're going to have, for whatever reason, increased population of the Malassezia species. 04:05 Sometimes other fungi can do this, but typically it's Malassezia. 04:09 And now we have an increased inflammatory response. 04:12 Yeah, those guys shouldn't be there in such abundance. 04:15 The body responds by producing more inflammatory cells specific for the fungus. 04:22 As a consequence, the cytokines and the inflammatory response of those cells ends up driving the sebaceous glands to increase their proliferation. So we get more cells, but they also increase the production of their contents. Remember, this is a holocrine secretion. 04:39 So the entire cell fluffs with its lipid content into the hair shaft that gets out along the surface onto the surface of the skin. 04:48 And that's going to give us that greasy kind of component, the yellow greasy portion of the plaque. 04:56 So there is individual susceptibility. 04:58 Some of us are born with more sebaceous glands or more active sebaceous glands, and those of you who have or have had severe acne know that it doesn't affect everybody the same. Stress, interestingly enough, because of adrenergic stimulation, can also drive those sebaceous glands to make, to proliferate and make more of their product. Okay, so there's individual susceptibility that can be intrinsic or it can be extrinsic. 05:25 Then there are other things that get superimposed. 05:28 So HIV infection by changing the kind of the inflammatory, the ability of the immune system to respond can lead to extensive over, you know, overgrowth of the fungus because we're not keeping them in check. 05:43 So seborrheic dermatitis affects a significant proportion of patients with active acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. 05:50 It will also happen in patients who have very low CD4 counts for a variety of reasons, including in lymphomas where we have replaced the normal cohort of CD4 cells with the lymphoma cells or the leukemia cells and solid organ transplants, because we're immunosuppressing them. 06:09 Parkinson disease leads overall as a result of the the abnormal production of dopamine to increased sebum production. The exact mechanism is not well understood, but it is a known kind of effect seen in Parkinson's disease. And when we administered extrinsic levodopa as part of our therapy for the movement disorder of Parkinson, you can see improvement in the seborrheic dermatitis. 06:38 Alcohol use disorder creates changes associated with hyperplasia of the sebaceous glands not otherwise specified. 06:48 So too much alcohol or metabolites thereof actually influence the production of sebum and the expansion of the sebaceous glands. 06:58 In cold temperatures, we tend to make more of the sebum that is a protective response. 07:04 And so very cold weather can exacerbate seborrheic dermatitis. 07:09 And you may see some improvement if you move to tropical climes. 07:13 And then certain medications will also do the same thing again by acting specifically on the sebaceous gland kind of pathology or the sebaceous gland metabolism, and not particularly by changing the flora and fauna on the surface of the skin.

About the Lecture

The lecture Seborrheic Dermatitis: Pathophysiology by Richard Mitchell, MD, PhD is from the course Inflammatory Lesions of the Skin.

Included Quiz Questions

What is the typical age distribution pattern of seborrheic dermatitis?

- Bimodal, with peaks in infancy and adolescence/early adulthood

- Single peak in middle age

- Steady increase with advancing age

- Single peak in early childhood

- Continuous throughout life

Which microorganism plays the primary role in seborrheic dermatitis pathogenesis?

- Malassezia species

- Staphylococcus aureus

- Candida albicans

- Propionibacterium acnes

- Streptococcus species

Which systemic condition is most strongly associated with severe seborrheic dermatitis?

- HIV infection with low CD4 counts

- Type 2 diabetes

- Hypertension

- Osteoarthritis

- Heart disease

Which environmental factor typically worsens seborrheic dermatitis?

- Cold temperatures

- High humidity

- Hot weather

- Strong sunlight

- Moderate climate

Customer reviews

5,0 of 5 stars

| 5 Stars |

|

5 |

| 4 Stars |

|

0 |

| 3 Stars |

|

0 |

| 2 Stars |

|

0 |

| 1 Star |

|

0 |