Playlist

Show Playlist

Hide Playlist

Nephrolithiasis (Kidney Stones): Etiology, Epidemiology, and Pathogenesis with Case

-

Slides Nephrolithiasi.pdf

-

Reference List Nephrology.pdf

-

Download Lecture Overview

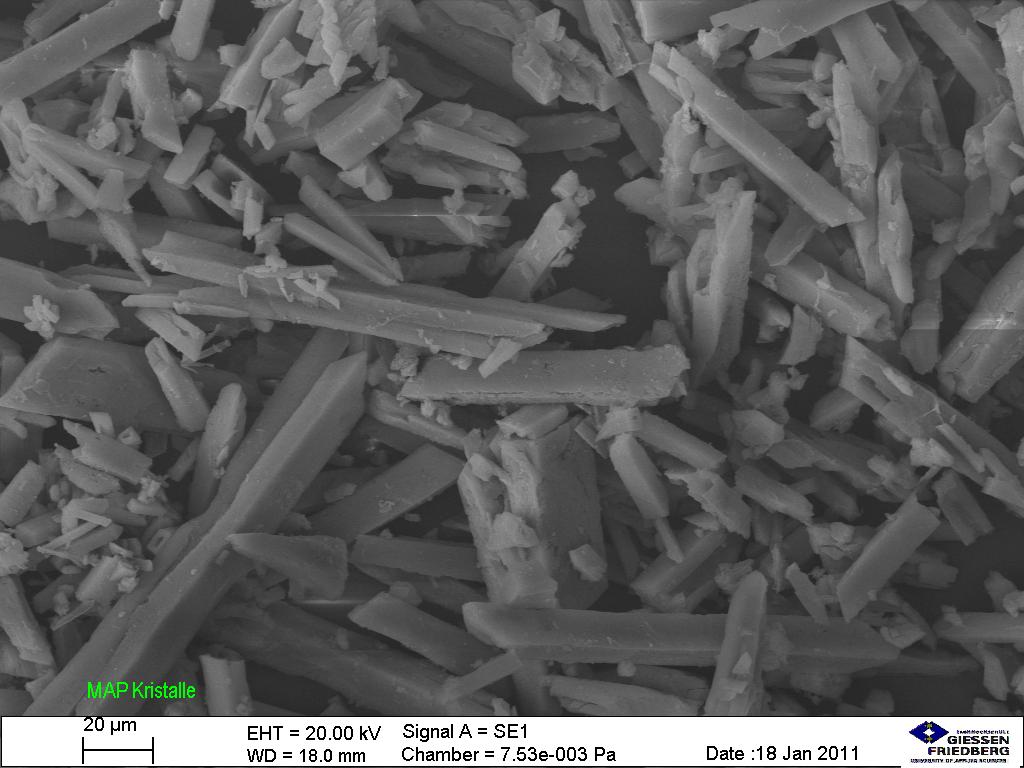

00:01 Hello and welcome back to the nephrology curriculum. 00:04 Today we're going to be talking about nephrolithiasis or stones. 00:08 So let's start out with a clinical case. 00:11 A 44-year old gentleman is seen in the emergency department for acute onset left-sided flank pain of 2 hours duration. 00:18 He rates the pain 10 out of 10 and he can't sit still because the extreme discomfort from the pain. 00:24 He denies fevers, chills, he's had some nausea in association with the pain but no diarrhea or other systemic symptoms. 00:31 He does note taking high-dose vitamin C supplements to prevent colds and he drinks several glasses of iced tea daily given that he's working outside in the heat as a construction manager for several hours of the day. 00:45 On physical exam, it's notable for left CVA or costocertebral angle tenderness to percussion His labs showed normal electrolytes and his urine analysis shows greater than 40 red blood cells per high power field. 00:59 So the question is, what is our next step to diagnosing this gentleman? Let's go back through our clinical history and see if we've got some clues. 01:07 So he's complaining of acute onset of colicky pain that's very suggestive of a ureteral stone. 01:15 Interestingly, he's also taking very high dose vitamin C and iced tea, both predispose patients to oxalate-based stones Working outside in the heat is also gonna predispose to stone formation due to dehydration and CVA tenderness along with hematuria, very suggestive of stone. 01:35 So our our next step, we want to image the patient and see if in fact he does have a stone. 01:41 So that's exactly what we do, we obtain a CT non-contrast of the abdomen and pelvis and that's what shown here in this particular image. 01:50 This is an axial section taken right through the kidneys and you can see that arrow is pointing in the left kidney to a bright hyperdensity, that in fact is a stone. 02:02 So the question is, what is the etiology of this patient's presentation? It's a stone, so this patient has nephrolithiasis. 02:12 So let's talk a little bit more about stones. 02:15 Stones are common in industrialized nations. 02:18 The lifetime risk of forming stones there is between men and women, so about 13% in men and 5% in women. 02:26 The incidence is about 1 per 1000 persons per annum and the peak incidence typically occurs in the third and fourth decade of life and increases with age until about 60 to 70 years The US prevalence has increased in stones from 3.2% in the late 1970s to about 8.8% in the first decade of the 2000 and that increas in prevalence really moves from the north to the south so may have something to do with the hotter climate. 02:57 White populations are greater in terms of stone formation the non-whites. 03:03 Stone types can also vary depending on geographic location. 03:07 For example, in the Mediterranean or Middle East we typically will manifest with uric acid stones. 03:14 In the United States, calcium oxalate or calcium phosphate are most common. 03:19 In the United Kingdom, magnesium, ammonium phosphate or struvite stones are the most common and then there are cysteine stones which are actually quite rare. 03:29 If we look at the distribution by stone type, you can see in this pie chart that clearly, calcium-based stones are the highest. 03:37 Sol typically, calcium oxalate and calcium phosphate make up 37% of all stones. 03:43 The next is calcium oxalate making up 26% of stones, and then followed by struvite stones making up about 22% of stones. 03:52 Then finally, we have calcium phosphate at 7%, uric acid at 5% and then cysteine only at 2%. 04:00 So how do the kidney stones form? It occurs when soluble materials supersaturates in the urine. 04:08 So let's go through that a little bit more closely. 04:11 Free ion activities of the stone components are gonna be affected by the following: the crystal component concentration, presence of inhibitors in the urine - these are things like to treat which chelates calcium, and the urinary pH. 04:25 High urinary pH may precipitate certain stone types while a low urinary pH precipitates others. 04:33 The level of chemical free ion activity where stones will neither grow nor dissolve is referred to as the equilibrium solubility product. 04:42 Urine becomes supersaturated above that level and when that happens, any stone present is going to grow in size How exactly does that happen? Ions joined together to form a stable solid phace and when homogenous, that results in crystals or crystalluria. 05:04 Calcium oxalate crystals attach to something called Randall's plaques These are plaques or areas of calcium phosphate deposits in the renal papillae shown here in the image on the right. 05:16 When they do that, it promotes stone growth. 05:20 And finally we have genetic polymorphisms that are associated with stone formers. 05:26 These are genes that code for proteins that regulate tubular calcium and phosphate reabsorption, proteins that prevent calcium salt precipitation, or aquaporins in the proximal tubule.

About the Lecture

The lecture Nephrolithiasis (Kidney Stones): Etiology, Epidemiology, and Pathogenesis with Case by Amy Sussman, MD is from the course Nephrolithiasis (Kidney Stones).

Included Quiz Questions

Which of the following is the gold standard modality of choice for detecting renal stones?

- Computed tomography scan without contrast

- Ultrasonography of the kidney and bladder

- Isotope renography

- Magnetic resonance imaging

- Computed tomography scan with contrast

Which of the following is true regarding the epidemiology of nephrolithiasis?

- Stone types vary depending on geographic location.

- The incidence decreases with age.

- It is more common in patients of Asian ethnicities.

- It is more common in female patients.

- Struvite stones are the most common type in the United States.

Customer reviews

5,0 of 5 stars

| 5 Stars |

|

2 |

| 4 Stars |

|

0 |

| 3 Stars |

|

0 |

| 2 Stars |

|

0 |

| 1 Star |

|

0 |

2 customer reviews without text

2 user review without text