Playlist

Show Playlist

Hide Playlist

Ischemic Heart Disease: Plaque Changes and Adaptive Mechanisms

-

Slides Ischemic Heart Disease.pdf

-

Reference List Pathology.pdf

-

Download Lecture Overview

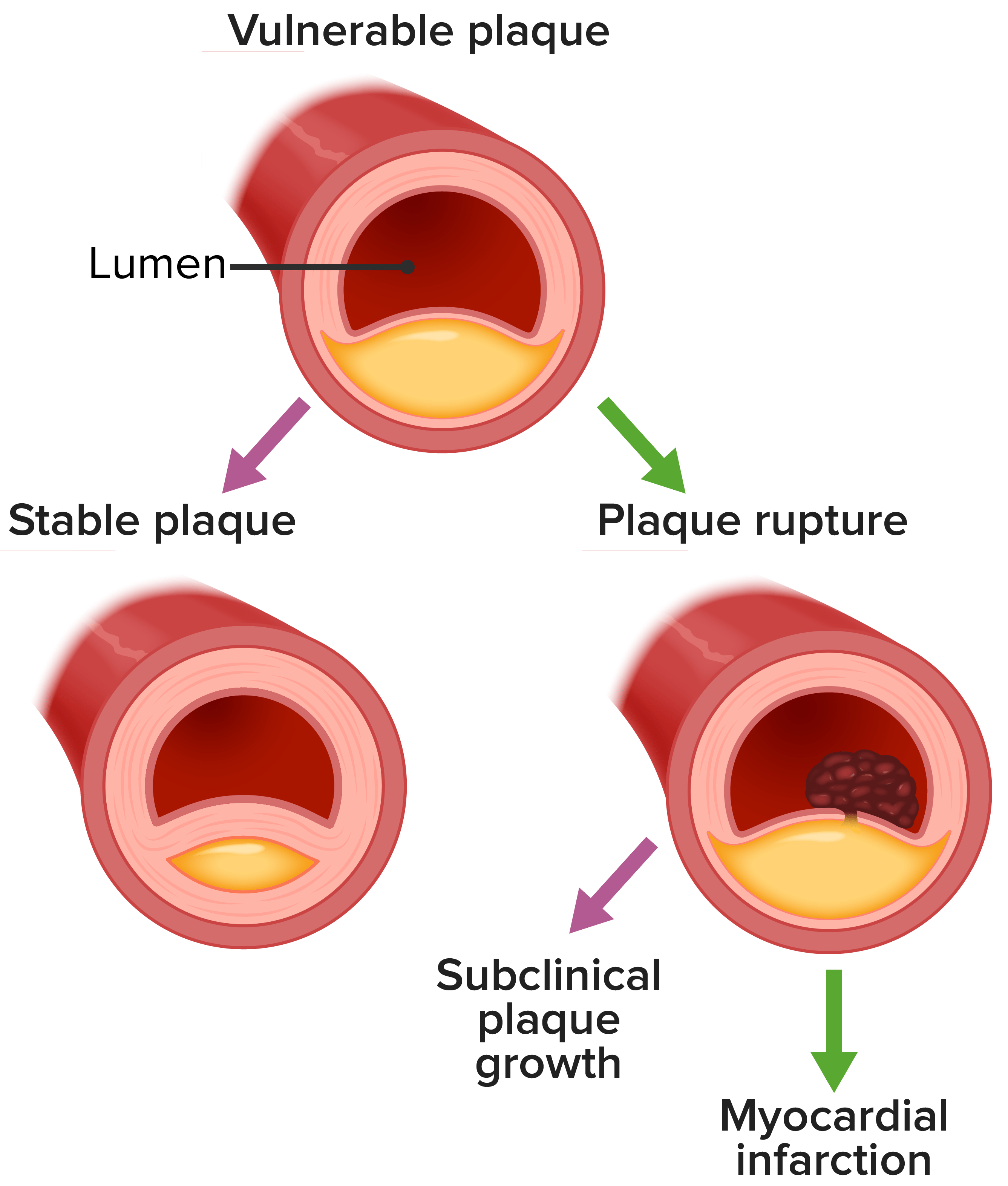

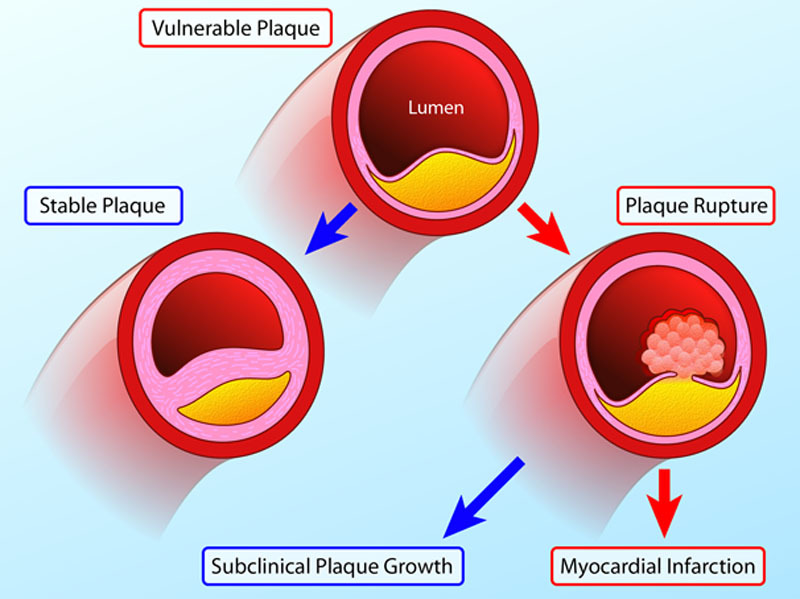

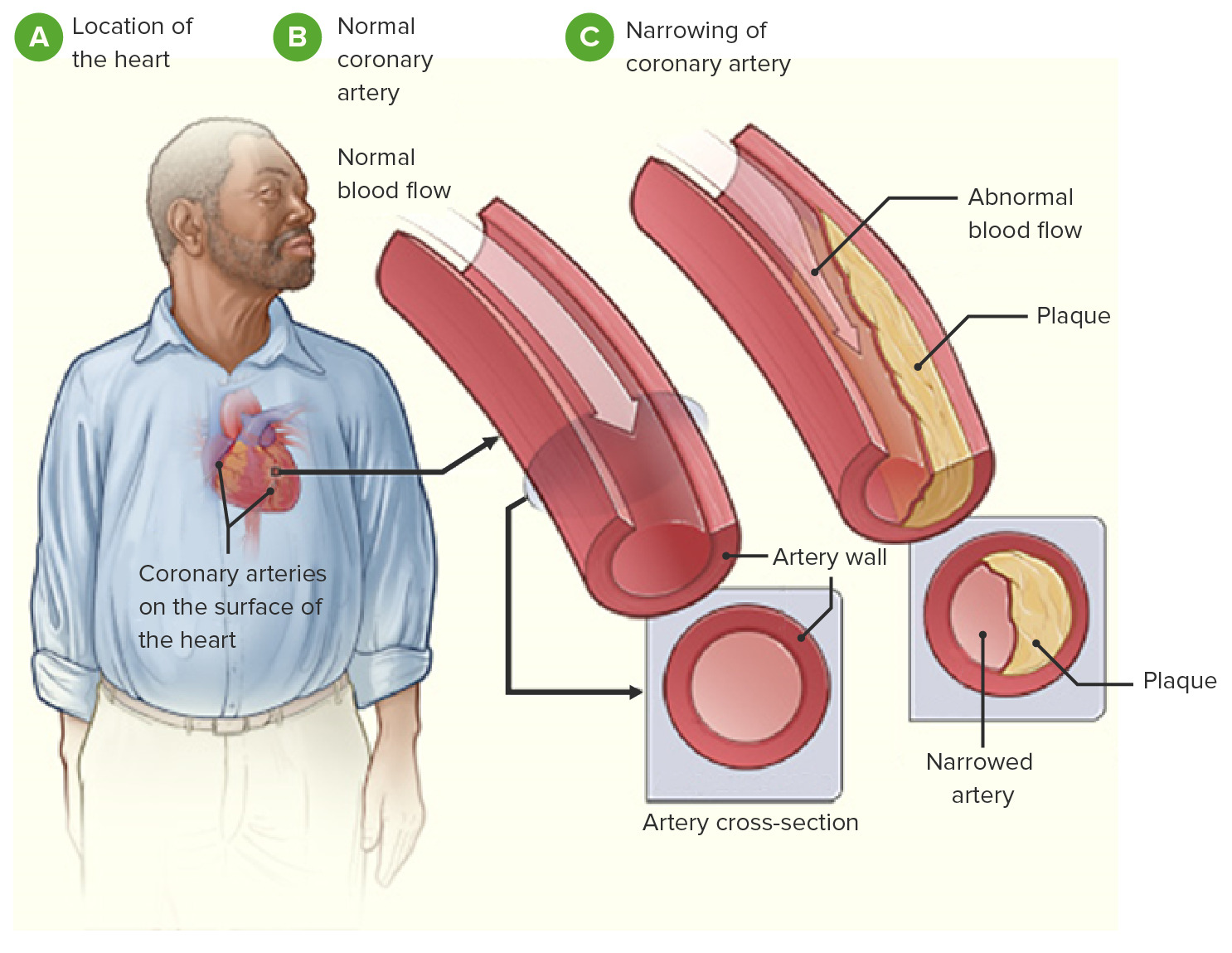

00:01 So plaque changes. 00:02 There are a variety of ways that the plaque can rupture, erode, whatever. 00:07 So if you have inflammation that can cause endothelial cell erosion. 00:12 If you have a toxic exposure from whatever that is. 00:14 It could be various chemotherapies. 00:16 It could even be infection, whatever. 00:19 You can have endothelial cell injury and apoptosis that then leads to a plaque erosion. 00:26 So I haven't really ruptured the atherosclerotic plaque, but now, I have a surface that is not covered with endothelium and that can be a source for thrombosis. Okay. There you go. Thrombosis. 00:39 There can also be intrinsic factors that decide whether or not, or contribute to whether or not a plaque will rupture. 00:47 So the plaque composition is really important. 00:49 If you have a very thick-walled fibrous cap with a lot of connective tissue in it, that's not going to rupture. If you have a very fibro, fatty, if you're very fatty, atheromatous core, big old globule of fat and cholesterol and necrotic debris with a little tiny thin cap, that's going to be much more likely to rupture. 01:09 So the plaque composition and structure actually makes a difference. 01:11 Parenthetically, things like statins change the overall structure of a lot of plaques. 01:18 They make them more fibrotic. 01:20 So one of the other benefits of statins other than cholesterol lowering is that we get more fibrotic plaques. 01:26 And even though we haven't changed particularly the size of the plaque, we make it less likely to rupture. 01:32 Okay. Other extrinsic factors, blood pressure, platelet reactivity. 01:37 So increased blood flow, increased heartrate. 01:41 All those things will make a plaque more likely to rupture. 01:46 And if there is increased platelet reactivity, we're more likely to form thrombus. 01:50 Mechanical stresses, such as increased turbulent flow will drive the process, and we get an acute plaque rupture, which of course, will lead to thrombosis. 02:03 We have ways to adapt and hopefully, prevent some of this. 02:08 So normally, and we'll - I'll show you a diagram in a minute, but normally, for example, in the coronary circulation, you have the left anterior descending territory, the left circumflex territory, and the right coronary artery territory. 02:23 Those territories have a zone in between that get perfusion from both, say, the left anterior descending and the right coronary artery. 02:32 There is a watershed zone in there. 02:34 And there is some interconnection between the arteries. 02:37 That is a collateral flow. And if we have partial obstruction of one vessel, the collateral flow from the other vessel that can feed into that territory can takeover. 02:50 In fact, it can become fairly much more robust. 02:53 So if I have a progressive low-level occlusion that occurs in a coronary artery over years, the other coronary arteries can take over for that territory. 03:06 And they can provide compensatory blood flow. 03:09 And in fact, that collateral perfusion can even protect against an MI if the original vessel is totally obstructed. 03:18 Okay, so just keep that in mind as well. With acute coronary blockage, however, there is no opportunity for the collateral flow to open. 03:28 So then you will have an infarction. 03:31 Alright, so this is just looking at a heart to make this point about the collateral circulation. 03:37 This is showing you the left anterior descending. 03:39 This is a heart that has been permeabilized with methyl salicylate. 03:43 so you can see through the tissue. 03:45 And then we've injected the coronaries with a red latex. 03:49 So the left anterior descending, the LAD, is shown there. 03:53 And the right coronary artery is shown there and that's the left circumflex. 03:57 Now there are collaterals between those various territories that can allow collateral perfusion of the zones in between, the watershed zone. 04:07 So even if I lose my LAD but I lose it slowly enough, the right coronary artery can take over for that territory. 04:14 It may not take over entirely for all the left anterior descending territory but it can compensate. 04:20 Similarly, between the left circumflex and the LAD, we also have another watershed zone. 04:25 So there are compensatory mechanisms. 04:27 All things considered, we really don't want to have atherosclerotic disease. 04:30 And if you do, you probably want to get it treated. 04:33 And with that, we'll conclude ischemic heart disease.

About the Lecture

The lecture Ischemic Heart Disease: Plaque Changes and Adaptive Mechanisms by Richard Mitchell, MD, PhD is from the course Ischemic Heart Disease.

Included Quiz Questions

Which medications stabilize the atherosclerotic plaque by thickening the fibrous cap?

- Statins

- Nitroglycerin

- Beta-blockers

- Heparin

- Spironolactone

Which of the following is an intrinsic factor that indicates whether or not the atherosclerotic plaque will rupture?

- Plaque composition

- Platelet reactivity

- Hypertension

- Hypotension

- Heart rate

Customer reviews

5,0 of 5 stars

| 5 Stars |

|

1 |

| 4 Stars |

|

0 |

| 3 Stars |

|

0 |

| 2 Stars |

|

0 |

| 1 Star |

|

0 |

you make everything so so simple...loved your videos thank you for clearing the whole concept