Playlist

Show Playlist

Hide Playlist

Hemodialysis and Peritoneal Dialysis: Access

-

Slides Renal Replacement Therapy.pdf

-

Reference List Nephrology.pdf

-

Download Lecture Overview

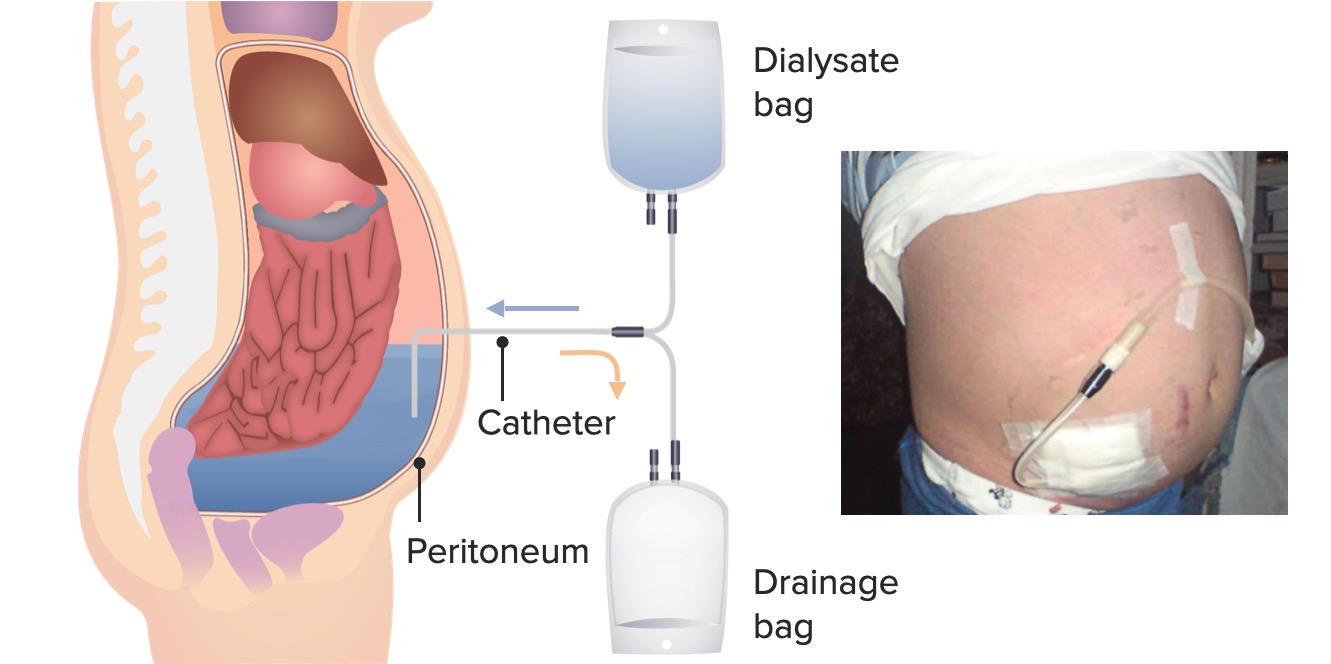

00:01 So when we're talking about hemodialysis. 00:03 And our patient chooses that as their modality, and that's the therapy they want to do. 00:08 It's critical to ensure that they have the appropriate vascular access. 00:12 Remember, we're hooking them up to this machine and we're talking about very high blood flows potentially 500 mL/minute. 00:19 Now, could you imagine just taking your antecubital fossa with the small vein in there and trying to pull out 500 mL/min? It's impossible. 00:27 So therefore, we can create something called an arteriovenous fistula. 00:32 That's where we actually connect the artery to the vein. 00:35 So by arterializing that vein it allows cannulation with a large bore needle up to 15 gauge so that we can access very high blood flows at 500 mL/min during hemodialysis. 00:47 Now, what's nice about an arteriovenous fistula or an AV fistula is that it has the longest lifespan and because it's all native. 00:54 We're working with native vessels, then it has a very low infection rate. 00:58 So in my patients, that is my preferred access, If they're choosing hemodialysis, I absolutely am going to consult my vascular surgeons, and I'm going to ask them to really try to place an arteriovenous fistula. 01:09 Now, if my patient perhaps has diabetes, and they have poor vessel targets, or they're a pediatric patient, or they just have small vessels in general. 01:17 It may not be possible to create a native arteriovenous fistula. 01:22 So in that case, we actually can create an arteriovenous graft. 01:25 And what that means is we're putting a material between that artery and vein, we're still connecting them, but it might be with something like PTFE. 01:33 When we do that, that allows us again to be able to canulate that particular graft, and we could use, again, those higher blood flows in order to achieve a blood flow of 500 mL/min in our patients undergoing hemodialysis. 01:47 Problems with having an AV graft is that they have a higher rate of thrombosis. 01:52 Remember, these are not native to their circulation. 01:55 So anytime blood interfaces with something that's not native, it's going to activate the clotting cascade. 02:00 So it's not uncommon for these patients to have thrombosis in those graft, and they can have stenosis as well. 02:06 And patients also can develop a higher rate of infection because again, we're dealing with something that's not native. 02:12 It's not native vessels. 02:13 We're putting something that's foreign in their body, so there is a risk of having infection. 02:17 And finally, in terms of vascular access for hemodialysis, there's the tunneled vascular catheter. 02:23 These are definitely the least desirable out of all three of these different types of vascular accesses. 02:30 Why? Because it is a piece of plastic that we are putting into our patients. 02:35 So you can imagine the rate of infection is quite high. 02:39 So how this works is we might take a catheter, it's relatively large-bore, it goes into the internal jugular vein. 02:46 It actually gets tunneled out through the chest so that there's some protection there from infection. 02:51 And then the tip of that catheter goes into that cavoatrial junction. 02:55 Besides having the highest rate of infection, there's also an increased risk of great vessel stenosis. 03:01 So anytime we have a catheter laying in our blood vessels, remember that's not native to those blood vessels. 03:07 And as it's touching those blood vessels, it's stimulating those endothelial cells to proliferate. 03:12 So that can actually cause a narrowing or what we call stenosis of those vessels. 03:17 That's hugely problematic because if I wanted to create a fistula downstream in the arm, either the upper arm or the forearm, I won't be able to have those developed if these great vessels are narrowed. 03:31 So we think about access for peritoneal dialysis. 03:34 We're actually using a peritoneal dialysis catheter that goes into the lower quadrant of the abdomen. 03:40 So typically, patients prefer to have that peritoneal dialysis catheter in the lower quadrant of the abdomen so that they're not visible if they want to wear a shirt that shows a little bit up here, and that it's comfortable to wear with their clothing. 03:53 But one of the things is that it's very critical to talk with your surgeon or your interventional nephrologist, who's placing that catheter. 04:00 If I have a patient who's coming in and they tend to have a very large pannus, I absolutely do not want that catheter to be underneath that pannus, that is just asking for an exit site infection and the patient won't be able to easily get to that catheter. 04:15 So it really depends on the patient's body habitus. 04:17 And it's important for the patient, and the surgeon, or the interventional nephrologist who's placing that catheter to determine together where best that catheter can go. 04:25 Now that catheter tunnels in the skin and then goes through to the peritoneal cavity, and that tip of the catheter is in that pelvic area. 04:34 It's important again, to really trust your surgeon or your interventional nephrologist, who's placing this catheter because there's lots of things like omentum and other things in the peritoneal cavity that can entangle that catheter and it's critical to ensure that that catheter is working. 04:49 So oftentimes, when we're placing those catheters, we might do an omentopexy or something else that can allow that catheter to be relatively free and floating in that peritoneal area.

About the Lecture

The lecture Hemodialysis and Peritoneal Dialysis: Access by Amy Sussman, MD is from the course Renal Replacement Therapy.

Included Quiz Questions

Which of the following complications is associated with central venous catheters?

- Infection

- High-cardiac output heart failure

- Dialysis access-associated steal syndrome

- Lower extremity swelling

Which of the following statements is true regarding dialysis access?

- Arteriovenous fistulas are associated with the lowest complication rates.

- Arteriovenous fistulas are preferred over arteriovenous grafts in patients with inadequate vessels.

- Arteriovenous grafts have the highest risk of infection.

- Central venous catheters are the most desirable access method.

Which of the following vascular access methods has the longest lifespan?

- Arteriovenous fistula

- Arteriovenous graft

- Central venous catheter

- Peritoneal dialysis catheter

Customer reviews

5,0 of 5 stars

| 5 Stars |

|

5 |

| 4 Stars |

|

0 |

| 3 Stars |

|

0 |

| 2 Stars |

|

0 |

| 1 Star |

|

0 |