Playlist

Show Playlist

Hide Playlist

Concepts – Vertebral Column

-

Slides 02 Abdominal Wall Canby.pdf

-

Download Lecture Overview

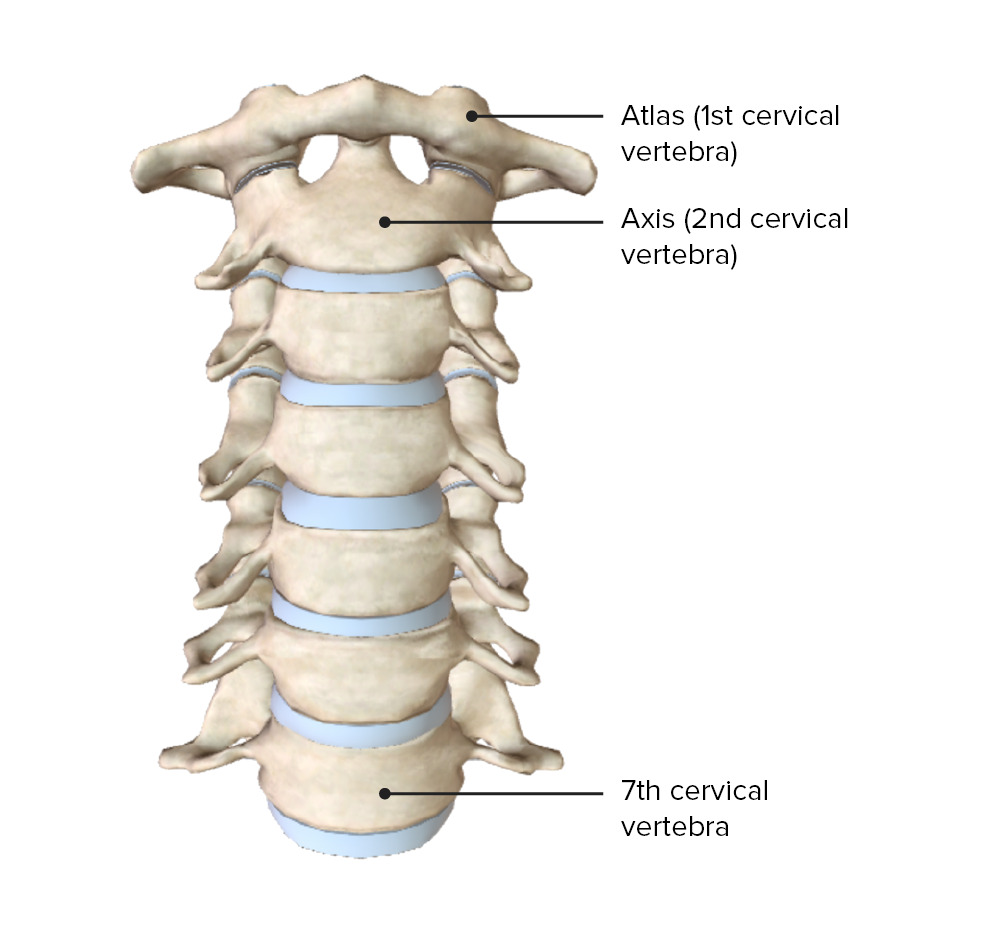

00:01 I welcome you to this lecture on the “Vertebral Column”. 00:06 At the conclusion of this lecture, you, as a learner, should be able to describe the vertebral segments and the number of vertebrae in each segment. You should be able to describe the vertebral curvatures and their formation. Describe the formation of inner vertebral foramina and their clinical significance. Describe the structural blueprint of a typical Vertebra. Compare and contrast the structural features of vertebral segments. And then, lastly, you should be able to describe the vertebral articulations and ligaments and their functions. 00:42 I then will summarize the important take-home Messages, and then lastly, I’ll provide attribution for the images that were used throughout this lecture. 00:56 Here is a body map to quickly orient us to the region of interest. And we’re going to focus here on the posterior view. And you see this furrow right down the midline. This furrow represents the location of structural elements of our vertebral column. And this would be the spinous processes. So, we’re going to be looking right along this area to define the segmentation of the vertebral column. 01:32 First, let’s take a look at some basic concepts of the vertebral column and our starting point is with segmentation. 01:46 What we have within the vertebral column are various segments. We will have a cervical segment and that is represented by the first seven vertebrae that we see here in the anterior view and then we also see the seven vertebrae posteriorly. The thoracic segment will be the next twelve vertebrae. And we see the general location of the thoracic vertebrae in through here. And then posteriorly, we are looking in this general region for our twelve thoracic vertebrae. Just inferior to the thoracic segment, we have the lumbar region and we have five lumbar vertebrae and our starting point here, let’s go with L5, the fifth lumbar vertebra. So, there is the fifth one. Above it is 4, 3, 2 and then 1. So, here we have the five lumbar vertebrae. And then posteriorly, we start with the last one, 5. 02:50 There’s 5, 4, 3, 2, 1. 02:54 The next segment is the sacrum. And in the adult form, the sacrum is formed by a fusion of five vertebrae. And then lastly, we have the coccyx, coccygeal vertebrae. Typically, will number four. However, there is some anatomic variability. You may have three coccygeal vertebrae or you may have as many as five. But, we’re going to stick to the number four. And so, if we add 7, 12, 5, 5 and 4, we have 33 vertebrae within the vertebral column. 03:37 The vertebral column also will present two curvatures - a primary curvature and a secondary curvature. If we look at primary curvatures, we were born with these. These will develop during the foetal period. And there are two primary curvatures that develop. 04:01 The first is the thoracic curvature that we see in through this area, anterior is to our left, posterior is to our right in this lateral view and if you look at it anteriorly, you will note that the thoracic primary curvature is concave. The other primary curvature is the sacral curvature and it too is concave. 04:27 And we’ll pause here just for a moment of reflection. Let me ask a basic question related to the curvatures, the primary curvatures. Why would we want to have or wish to have primary curvatures in the thoracic and sacral areas that are concave in their appearance? And the reason that we want to have these concave primary curvatures is to increase the volume within the thoracic cavity, to house our thoracic organs or viscera. Similarly, in the pelvic area, which is a very narrow region anatomically, we’ll have a primary curvature here to house the pelvic viscera. 05:27 Secondary curvatures, of which there are cervical and lumbar secondary curvatures, are going to develop after birth and they will represent developmental milestones. So, if we take a look here in the lateral view of the vertebral column, we see our cervical secondary curvature, this level. And if we look anteriorly, we see that it projects in a convex manner. 05:56 Also, the lumbar curvature, which we see here, has a convexity to it as well. What happens developmentally when you think about an infant starting to lift its head, that’s when you’ll start to develop the cervical secondary curvature. Then the infant is, a few months later, going to learn to walk. And when the infant starts to stand on his or her feet and starts to walk, the lumbar secondary curvature will develop. 06:36 One might also ask how do these curvatures develop? The primary curvatures are due to the differences in the height of vertebral bodies. So, if we take a look here, we’re looking at a thoracic vertebra. Here’s the anterior portion of the body and here’s the posterior portion of the body. You cannot really perceive it here, but the anterior height of the vertebral body is a little bit shorter than the posterior height. Therefore, these are somewhat wedge-shaped and when you stack multiple thoracic vertebrae upon one another, you will then develop this primary curvature. Same thing happens with the sacral vertebrae as well. 07:25 The secondary curvatures again develop at developmental milestones and what we have between the vertebral bodies are intervertebral discs. And so, when you develop your secondary curvatures, you’ll have a height difference between the anterior part of the disc and the posterior part of the disc such that the anterior portion will be thicker than its posterior portion. And then that will confer the convexity that we see to our secondary curvatures. 07:56 One of the basic functions of the vertebral column is to protect the spinal cord and the spinal nerves that issue from the spinal cord. Once the spinal nerves are formed, they need a doorway or an exit outwards and that is mediated by the presence of intervertebral foramina. And if we take a look, when we stack our vertebrae upon one another, we will see these openings or spaces here and these are the inner vertebral foramina. And the typical spinal nerve will be transmitted at each of these particular levels as we move up or as we move down the vertebral column. 08:44 These intervertebral foramina may become stenotic. And when they become stenotic, they may put or compress the typical spinal nerve that leaves the foramen and as a result, neurologic symptoms can be felt by the individual affected. As a consequence then, these are loci of clinical interest.

About the Lecture

The lecture Concepts – Vertebral Column by Craig Canby, PhD is from the course Abdominal Wall with Dr. Canby.

Included Quiz Questions

What is the total number of vertebrae in a human spine?

- 33

- 22

- 37

- 44

- 11

What is the shape of a cervical curvature on a lateral view when looked at from the anterior side?

- Convex

- Concave

- Flat

- V shaped

- Triangular

What structures pass through the intervertebral foramina?

- Neurovascular structures

- Musculocutaneous structures

- Musculoskeletal structures

- Lymphatics

- Nothing passes through them.

What can cause the compression of spinal nerves?

- Stenosis of intervertebral foramina

- Extra concavity of the spine

- A tumor on the skin of the back

- Damage to the femoral nerves

- Bedridden patients

What vertebral curvature develops when an infant begins to stand up and learn to walk?

- Lumbar curvature

- Cervical curvature

- Thoracic curvature

- Sacral curvature

Customer reviews

5,0 of 5 stars

| 5 Stars |

|

2 |

| 4 Stars |

|

0 |

| 3 Stars |

|

0 |

| 2 Stars |

|

0 |

| 1 Star |

|

0 |

Thank you Dr. Canby for your succinct yet informative introduction to the concepts of the vertebral column. The pictures and pauses were very helpful, as I was able to follow along with the presentation. You presented the information intuitively.

It was very nice lecture as i get a new informations which could be difficult to figure it out by reading textbook only. Thank you very much