What Is Instructional Design?

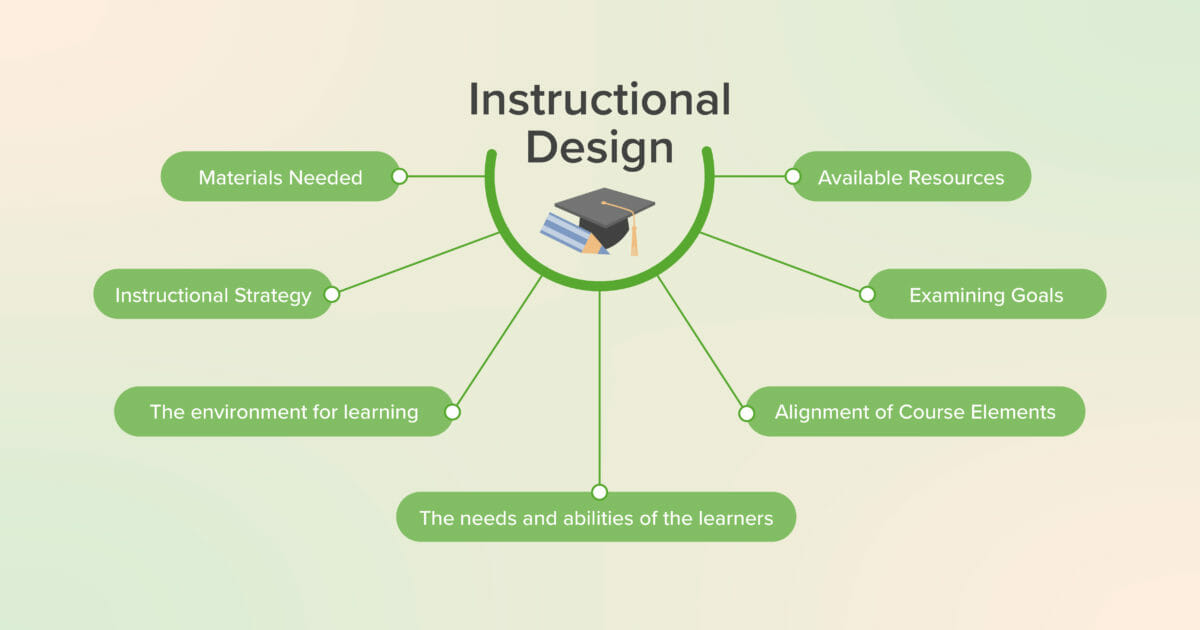

Instructional design has been defined as a body of knowledge that prescribes actions to optimize learning outcomes, therefore linking learning theory to educational practice(1). While instructional design includes actions familiar to educators such as creation of content and assessments, the systematic design of instruction entails all steps necessary to ensure development of high quality of learning experiences from identifying the need for instruction to the final stage of evaluating whether the desired learning occurred. Instructional design is systematic, where the pieces are interrelated, cohesive, and outcome-based to ensure the alignment of essential learning elements. Systematic instructional design considers every aspect of the teaching and learning process: examining goals, the learners’ needs and abilities, the environment for learning, the resources available, and desired performance to develop the assessments, the instructional strategy, and the necessary materials.

In medical education, educators are under increasing pressure to address the demands of 21st century medicine by producing healthcare providers who are more knowledgeable, skilled, and able to communicate effectively. An increasing base of knowledge compounded with advances in diagnostics and treatment options mean doctors must know and do more than ever before. The need for effective and efficient instruction is now a necessity, not a luxury. Students don’t just need to pass their courses, they need to excel in their program, in their qualifying exams, and meet professional competencies. Instructional design helps medical educators ensure they are maximizing the effectiveness and efficiency of instruction by integrating evidence-based practices to create high quality, aligned instruction(2).

Instructional Design Models

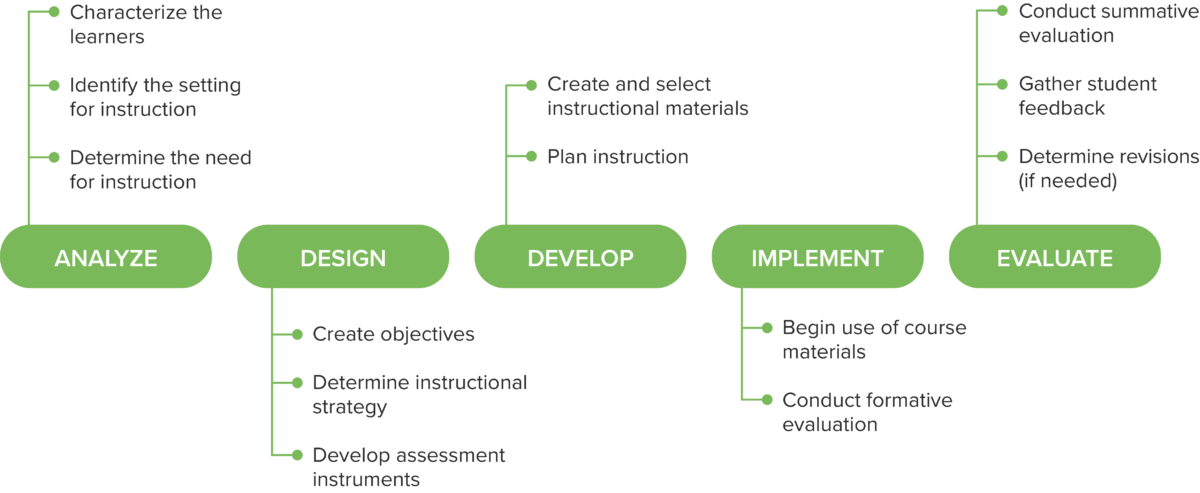

Just as there is no one-size-fits-all model to instructional strategies, there are many instructional design models, each with their own strength and emphasis. Many have similar basic features, with most being variations on the generic ADDIE problem solving model: Analyze, Design, Develop, Implement, and Evaluate.

Linear design process: ADDIE. A linear systematic design process in which each step is fully developed and informs the next step in the process.

In the analysis phase, the instructional designer considers who the learners are as well as the goals, needs, and resources available for instruction. In the design phase, the instructional designer works with faculty to determine objectives, an instructional strategy, and determine how the students will be assessed. From there, the development phase creates and curates materials and plans the instruction. In the implement phase, the instruction is enacted. If possible, instruction can be reviewed before the course begins by students or faculty, but if not, instruction can be evaluated formatively during the course. Finally, the evaluate phase examines the results, considers student and faculty feedback, and determines the need for revisions.

This is considered a linear model because one step is completed and leads to the next step. Instruction or changes to instruction are generally not enacted until fully developed. Linear design can be time consuming and resource intensive, but result in high-quality, usable products whether it is a full course, modifications within an existing course, or a new tool for learning. This is beneficial for programs that need to be effective at launch, such as safety training on a new medical device or training for the care of critical patients where learners must be fully proficient after training.

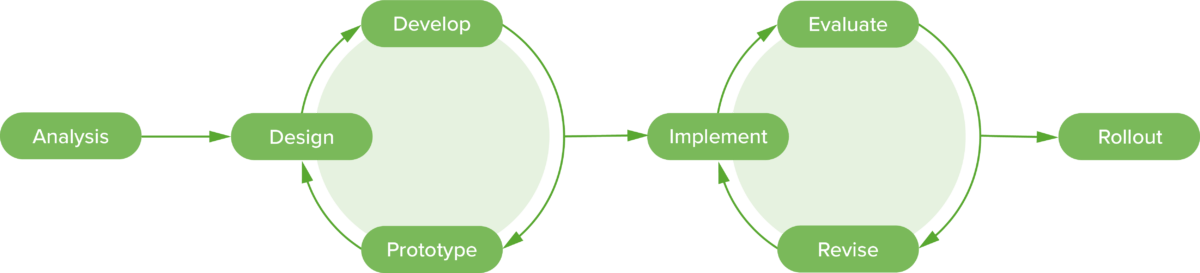

Other variations are more iterative, favoring the design process used in software development that employs rapid prototyping. Agile design creates a usable product faster but may need numerous revisions to become high quality and effective. An agile approach can save time and money by making adjustments and debugging as the instruction is developed. This can be beneficial when it is known in advance that revisions will be needed and can be planned into the project, such as the development of a computer-based surgical simulation or in a rapidly changing environment, such as the development of COVID training (3,4). Agile design can also be beneficial for making small incremental changes when broad changes are not feasible due to time and cost constraints. For example, medical educators may wish to pilot a module within a course as a template for future changes in that course or others (5).

Agile Process: the SAM2 model(6). A design model in which prototypes are developed and tested iteratively, allowing for regular revisions during the process. (modified by Lecturio)

Many models fall somewhere between the two, allowing for frequent revisions during the design and development phases. For example, goals and objectives that are formed early in the design process might not be realistic to fit into a lesson, module, or course, thus time constraints require the educational team to reassess what is essential. Frequently, one module of instruction is fully developed as a prototype before the rest of the course is designed (5). To further illustrate these examples, a case study is presented later in this article to demonstrate AVIDesign, a systematic model with agile elements.

Benefits of Systematic Instructional Design

Educational publications and sites are packed with ideas, trends, and suggestions. Implementing change haphazardly or based on fads may not only lack the desired outcomes but may increase frustration, decrease the effectiveness of instruction, and waste both time and resources. Systematic design means one phase informs the next to make sure instruction is appropriate for the given context, developed with respect to the needs and goals involved, and evaluated for effectiveness.

Alignment

Systematic design ensures alignment between objectives, assessments, and content(7). Students become frustrated when they don’t know what is expected of them, what to study, or feel assessments are unfair. If students are presented with vast amounts of content but lack clear objectives or the objectives don’t match the assessments, they are unable to distinguish between what is “nice to know” and what is “need to know.”

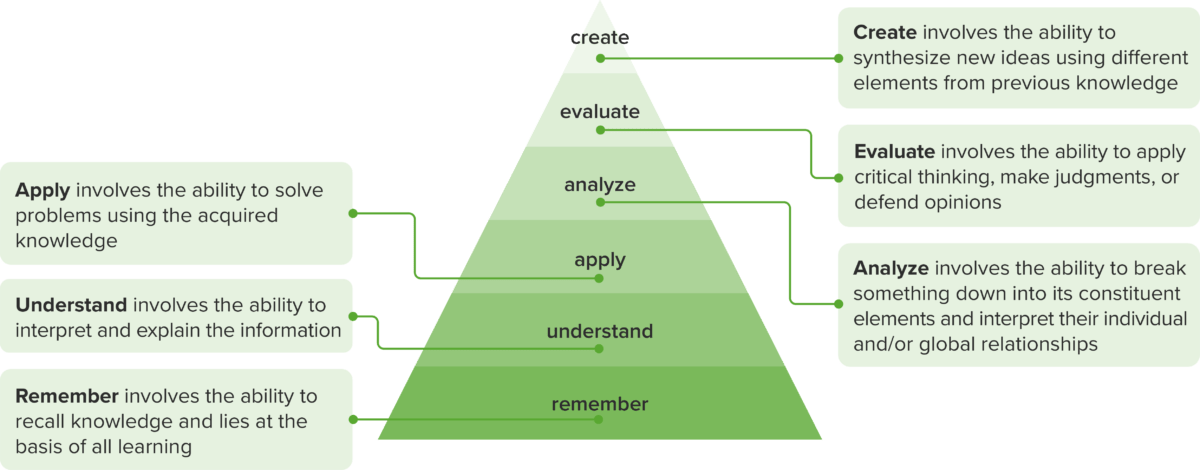

Furthermore, the level of expected performance given in objectives and assessments should align(8). These are frequently measured by taxonomies such as Bloom’s where the cognitive demands of the task are organized in a hierarchical fashion.

Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy(9) A hierarchical structuring of cognitive skills that help define objectives and align educational experiences and assessments. (modified by Lecturio)

For example, if an objective requires students to identify a disease, the assessment should also be at the “remembering” level, asking students for basic recall of the related facts. Misalignment may occur if the students are then assessed on their ability to compare and contrast with another diseased state (analyze) or determine a treatment plan (create), unless those were given objectives in the same lesson. Since medical programs and qualifying exams utilize multiple choice questions frequently, medical educators must be well versed in crafting quality assessments including high quality MCQs, to assess multiple levels of knowledge to match objectives, not just basic recall.

Finally, systematic design can also ensure programs meet program-level, national-level, and professional competency standards(7). Education in healthcare cannot only consider the goals and content of individual courses. Program coordinators need to ensure that learning goals are achieved at the right time and in the right place by aligning goals and objectives across programs and by keeping abreast of any changes in expectations in the profession at the national or global level.

Quality of Instruction

High quality instructional materials that are effective, efficient, and engaging can take extensive time to develop but by targeting curricular needs and student needs, instruction can be developed and delivered more efficiently than by trial and error. The use of evidence-based educational practices helps ensure the quality of the learning materials and experience.

The notion of evidence-based practice has evolved in many fields following the rise of evidence-based medicine. Much as in evidence-based medicine, effective educational design is dependent on practice grounded in empirical evidence rather than the use of fads, anecdotes, and flawed research(10).

AVIDesign (Agile eVidence-based Instructional Design Model) is being piloted in medical education to integrate agile methods and evidence-based education into systematic instructional design(11). (See Case Study below.) AVIDesign posits that evidence comes in different varieties that may inform design:

- Evidence may relate to proposed learning outcomes. For example, it may relate to the most effective ways to teach students to interpret EKGs or how to develop effective communication skills with patients and families.

- Evidence may relate to learning theory, i.e. what research says about the design and delivery of instruction based on the way people learn. For instance, it may tell us about cognitive strategies such as spaced repetition and interleaving.

- Evidence may also relate to the instructional approach, or the way content is delivered. For example, research may provide information about best practices in case-based learning or the use of medical simulations. It may relate to the delivery method such as online or hybrid learning, or suggest the optimal length of a didactic lesson

Replicability of Material and Processes

When faculty design courses and materials, they often rely on their own experience to fill in the gaps in curricular resources. It may be difficult for someone else to step in to teach the class for a day, a week, or a semester in the same manner as the original instructor. If the course is passed to another instructor, they must redevelop the entire course with very few materials, perhaps based only on some objectives and a text that was used before. However, instructional design makes all steps of instruction explicit and replicable(7). A course should be transferable in its entirety to another skilled instructor. Similarly, the development of materials can be used as a template for other similar courses or modules. For example, if a module is developed for one course based on its learners and resources (e.g. learning management system and available texts, videos and question banks), other modules in that course or similar courses within the program could be developed using the same strategy and design with step-wise modifications to the objectives, content, and assessments.

Integration with Technology, Online and Hybrid Teaching

Online and hybrid teaching are not a simple matter of putting existing materials online. In the immediate shut-down caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, educators were forced to shift to emergency remote teaching, rapidly moving materials, instruction, and assessment online(12). Many educators had little to no experience with developing online courses while educational specialists and instructional designers were in short supply to provide assistance, leaving many educators on their own to make extensive course adjustments with sometimes unfamiliar technology. Following this abrupt shift, some educators have come to the inaccurate conclusion that online learning was inferior when the real issue was that there was not enough time to properly analyze, design, and develop courses and course materials. In other words, the instructional design was lacking.

As healthcare education programs acclimate to new paradigms, a systematic design process can help evaluate existing programs, identify new curricular needs, integrate technology and redesign courses or portions of courses that are not effective or efficient. Additionally, technology allows for the use of high-quality tools and resources that can be reused. Design grounded in evidence can help ensure the effectiveness of the materials developed so that time and energy needed to develop and integrate them is worthwhile.

Practical Applications in Medical Education

Collaboration with an instructional designer or other educational specialist who is well versed in the design of instruction can help guide medical educators who may not have the time or expertise to follow a systematic design process. While collaborating with an instructional designer, the medical educator’s role is the subject matter expert. The instructional designer will rely on you to be the expert in the medical content and when possible, provide information about the students, the learning environment, and available resources. Even if one does not have the opportunity to collaborate, the following process may be beneficial for the individual educator.

Case Study: Use of the AVIDesign Model

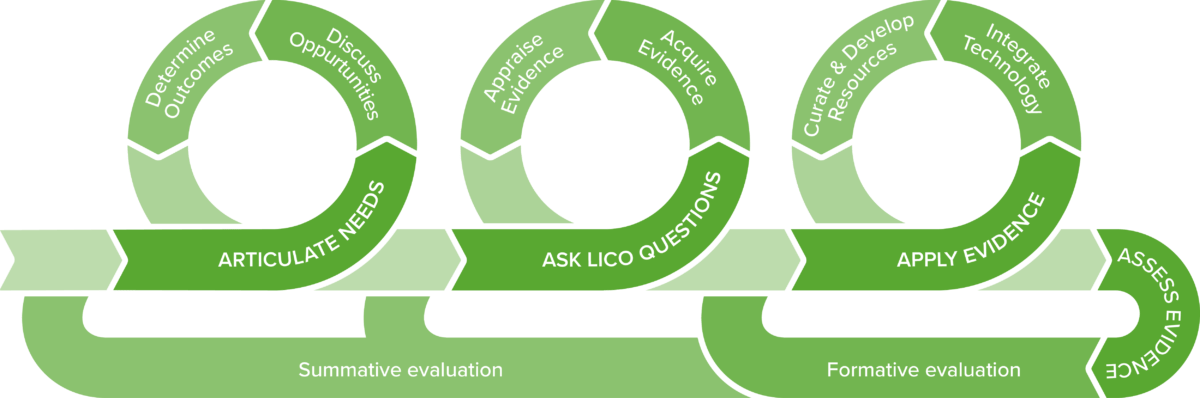

The AVIDesign model (Agile eVidence-based Instructional Design Model) integrates agile methods and evidence-based education into systematic instructional design. The model starts by “right sizing” the initiative by articulating needs, defining outcomes and discussing options. Next, the team asks LICO questions (like PICO questions that identify patient, intervention, comparison and outcome, LICO identifies learner, intervention, context, and outcomes), then uses these results to acquire and appraise evidence. The design phase includes defining objectives, aligning assessments, formulating the instructional strategy, and developing materials. Finally, formative and summative assessments are conducted to inform potential revisions.

AVIDesign Model(13). Incorporates agile methods with evidence-based practices to design high quality educational experiences. (modified by Lecturio)

To illustrate how this design process might work, a brief case study is presented: A faculty member has proposed a new elective in Palliative Care and Pain Management. The instructional design (ID) team works with the faculty member to help develop the course.

| Articulate: Right size the initiative | |

|---|---|

| What gap in the curriculum needs to be filled? | A new course in palliative care and pain management has been proposed and accepted. These topics are mentioned in other courses but this will be the first full course in the topic. This will also fill a department need for more online electives during Covid restrictions. |

| Who are the learners and what do you need them to be able to do after the module/course/experience? | The students are third and fourth year medical students.I expect this course to be an introduction to the topic to make them aware of palliative care issues. They need to be able to identify end of life needs, manage pain in basic cases, and communicate with families. |

| How much time do you have for design and delivery? | This course will begin in 6 months and I can meet once a week for an hour, plus planning by email as needed. |

| Ask, Acquire & Appraise: Analyze the context | |

| Ask LICO questions (Learners, Intervention, Context, Outcomes) | |

| Who are the Learners? What are their professional needs and interests? What motivates them? | This will be open to third and fourth year medical students. Since this is an elective, they would be choosing this course based on interest level but their professional goals may vary widely. They seem to be motivated by learning practical material that translates directly into patient care. |

| What is the desired intervention? Will it be online, synchronous? | This course will be an online course. There will be a mix of synchronous sessions and asynchronous work. We will meet 3 hours a week synchronously. The course may be 2 weeks or 4 weeks. |

| What is the context for learning and performance? [What materials and resources are available for learning? When, where, and how will students use this on the job?] | This course meets 3 hours a week synchronously and students are expected to spend a minimum 10 hours per week doing asynchronous work.

Our learning management system (LMS) provides quizzing tools, a discussion board, and I can integrate videos and other links. The students will be expected to use this information in hospital settings or hospice care. |

| What are the desired outcomes? | Students will determine treatment plans for simple cases involving end of life care, signs of impending death,and best practices involving opioid management. |

The ID team starts by helping acquire and appraise educational evidence. They review the research related to the goals, students, and resources, rate the research based on quality, strength, and relevance, and make evidence-based suggestions for the design of the course based on commonalities in the literature such as the use of real patient cases whenever possible, as well as a balance of knowledge, cultural/spiritual considerations, and communication exercises.

From these results, they collaborate to determine the objectives, assessments, and formulate an instructional strategy. An initial set of objectives is made for four modules. The first two will cover the basic concepts for pain management and end of life care, the second two modules (if offered, depending on whether it is a 2 or 4 week course) will repeat those topics, going more in depth and using more complicated cases. Because the course is pass/fail, the instructor proposes that the preferred assessments will be formative assessments consisting of discussions, individual feedback, and group debriefing. Based on the instructor’s educational philosophy, the learners’ interests, and the curricular needs, the ID team suggests 3 instructional strategies: The BSCS 5E model, Constructivist Learning, and the 5 Component Lesson Model (7,14–16). The instructor chooses the 5E model which guides the students through five major stages: Engage, Explore, Explain, Elaborate, and Evaluate. The team decides to prototype one module to be used as a guide for the rest.

From the development of the first module, the team would then plan a formative evaluation by asking a student to review the module and give feedback. Based on the student feedback, the team would make revisions and develop the other modules so the course is ready for full implementation. After the course, the instructor and the department use student feedback to determine the need for further revision.

Instructional Design Teams

Having access to an instructional design team can be highly beneficial to faculty who wish to design, redesign, or evaluate their instruction. Team members might include instructional designers, faculty members, technology experts, curriculum designers, and other subject matter experts such as healthcare professionals. Educational specialists can provide expertise to increase the strength of the design in terms of gathering evidence and providing guidance regarding learning theories and instructional strategies. Other specialists may save time by helping integrate technology or by helping build instructional materials.

While all of these things are valuable, even if faculty don’t have access to these experts, they can still follow a systematic design process on their own. Start small by working to identify one change or improvement to an existing course. When working individually, consider asking for input from fellow faculty members, former students, and school technology experts. Encourage students to give constructive feedback during and after course, allowing for anonymous feedback. Finally, use course data to review and compare the effectiveness of instruction.

Recommendations

Instructor Perspective

- When creating or adjusting material, use a systematic process to ensure effective instruction.

- Consider who the learners are, what motivates them, and what resources are available.

- Instructional design ensures the alignment of objectives, content, and assessments, i.e. the learners are being taught and assessed based on the desired outcomes.

- The design and development of instruction should be based on empirically validated evidence.

- When integrating technology, instructors should consider the students skills and motivation, the desired interactions, and the potential for high-quality web-based material to be created or curated to make instruction more efficient and effective. Technology can also be utilized to make the delivery of content more efficient, and to help implement and track the use of key learning strategies.

Student Perspective

- Pay attention to course expectations and lesson objectives. If they are unclear, ask for an explanation before issues arise.

- When asked for feedback, take the time to give constructive feedback. The evaluation of existing instruction improves education at every level.

- Follow the recommended learning strategies- they are specially designed to optimize learning although this might not be initially apparent.

Review Questions

(Please select all that apply.)

1. Which of the following are true about instructional design?

a. It can improve instruction by ensuring objectives, assessments, and materials are aligned.

b. Instructional design can only be used when creating a brand new course.

c. It can help integrate evidence-based educational practices into new and existing courses.

d. There is only one effective way to design courses..

2. An agile instructional design model often involves

a. A step by step process that results in a single finished product or course.

b. Multiple iterations that allow for frequent changes.

c. Prototypes that enable testing and debugging before the final product or course is launched.

d. A lack of flexibility to make needed changes.

3. Using Bloom’s taxonomy can help

a. Decide the appropriate use of technology.

b. Determine the strength of available evidence for an instructional strategy.

c. Create effective Powerpoint presentations.

d. Align objectives and assessments.

4. When designing instruction, it is important to consider

a. What resources are available.

b. What professional competencies are relevant.

c. Who the learners are.

d. What evidence is available.

Correct answers: (1) a,c. (2) b,c. (3) d (4) a,b,c,d.

Online Seminar

This online seminar from the Durable Learning series will focus on the the topic of Instructional Design, which has been defined as a body of knowledge that prescribes actions to optimize learning outcomes, therefore linking learning theory to educational practice. The systematic design of instruction entails all steps necessary to ensure the development of high-quality learning experiences. Our guest speaker, Dr. Atsusi Hirumi, shared with us some key instructional design concepts and his important work on agile evidence-based design which facilitates an effective implementation of instructional design steps into the educational process.

Watch the seminar recording:

Would you like to learn more? Explore the Pulse Seminar Library.