Learning is an integral part of our daily lives and is mentioned as frequently in academia as it is in everyday conversation. Having a long and storied history, the concept of learning itself has evolved from a philosophical discussion into an entire scientific discipline. Philosophical doctrines, learning theories, and scientific research in medical education paved the way for a best-evidence medical education approach for educators, which enables them to better design, plan, and assess how they teach.

How Learning Evolved in History

Historically, discussions around the concept of learning arose from philosophical debates in Ancient Greece. Plato ascribed to rationalism, while Aristotle championed empiricism.(1) Rationalism postulates that knowledge comes from innate reasoning(1), and it was reflected in medicine in a line of thinking that prioritized reason in figuring out how diseases occur.(2) Empiricism postulates that knowledge comes solely from experience(1), and it was reflected in medicine through a school of thought that focused on what diseases are, basing optimal treatments and diagnosis on past experience.(2) More recently, rationalism was subscribed to Descartes and Kant, whereas empiricism was notably subscribed to by Locke, Berkeley, Hume, and Mill.(1)

Later, the experimental approach replaced the conceptual one, galvanized by the research of early psychologists such as Wundt and Ebbinghaus, which was a notable starting point of psychology as a discipline.(1,3) This historical development was followed by other learning theories and schools of thought, such as structuralism, functionalism, and behaviorism, as well as other theories that are still in use.

Why Learning Theories Matter

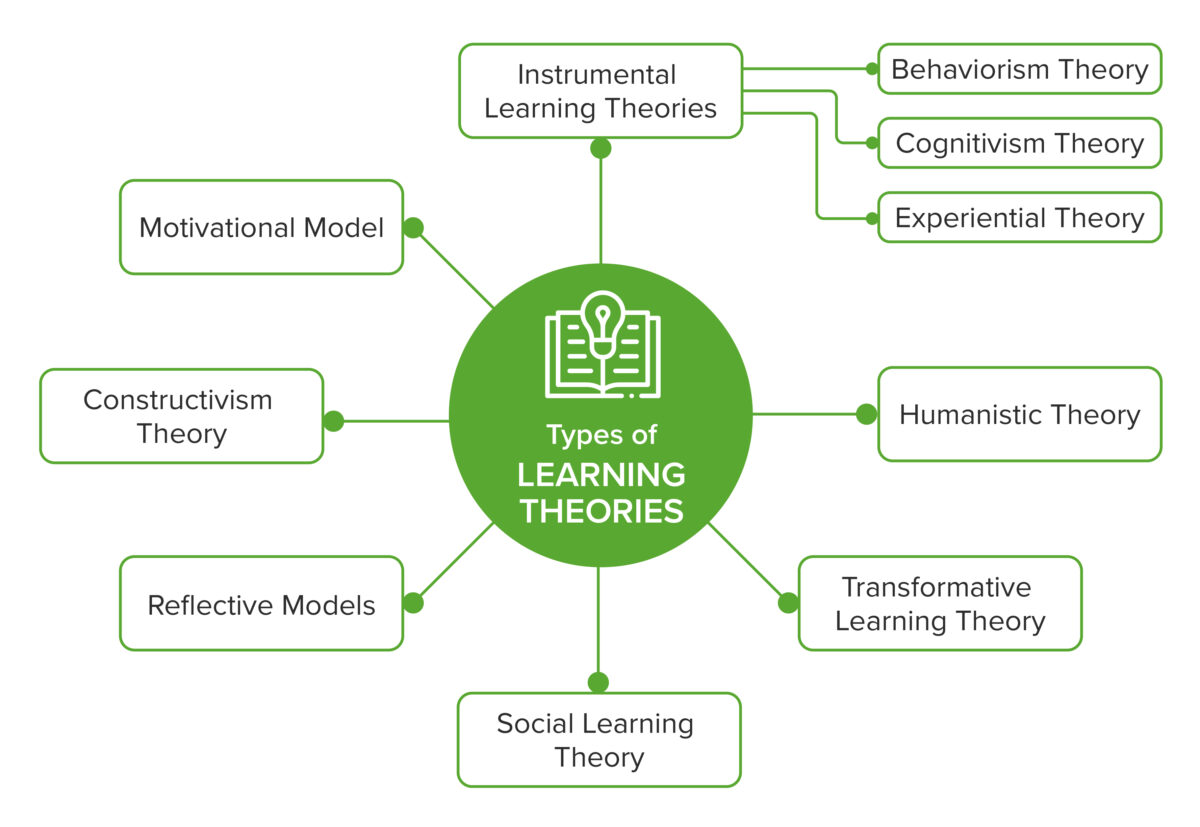

Learning theories attempt to describe how learning happens.(4) They matter not only because of the cyclical relationship they have with the research evidence in education,(5) but also because they help teachers become better educators by allowing them to (a) combine elements of different theories and better implement them in different situations;(6) (b) create better learning objectives, choose more appropriate instructional strategies, and implement better evaluation strategies;(7) and (c) understand that individual differences apply and that the responsibility for student performance should be attributed to these differences as well.(8) The following is an overview illustrating some prominent learning theories relevant to medical education. Further explanation can be found in our article, “History of Learning: From Theory to Evidence-Based Application in Medical Education.”

Overview of Learning Theories in the Context of Medical Education(7,8,9)

Evidence-Based Medical Education is the Way Forward

Medical education research as a turning point in medical education

Kuper, Albert, and Hodges pinpointed the 1950s as the beginning of a shift to a research-based approach to medical education. The promulgation of medical education research (MER) was mainly driven by socio-historical factors such as increased importance of scientific research in the medical community of the time, increased funding for research, and a renewed focus by regulatory bodies and the general public, among others, on accountability in the training of doctors.(10) This paradigm shift made it feasible for educators to apply a Best-Evidence Medical Education (BEME) approach in their daily teaching.

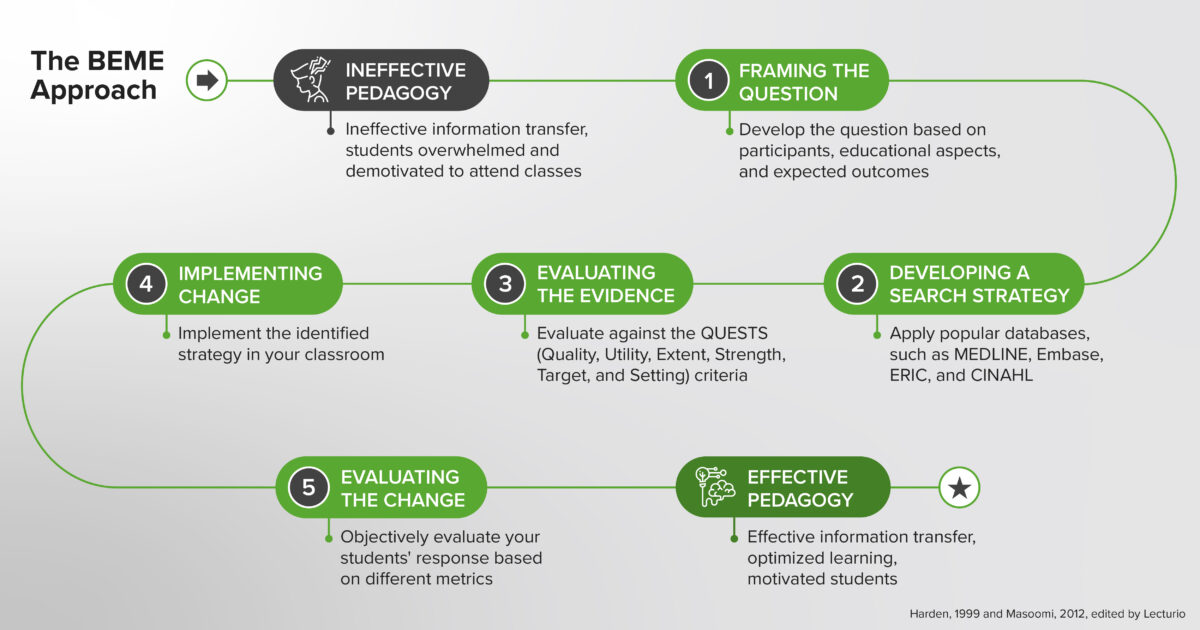

The BEME approach

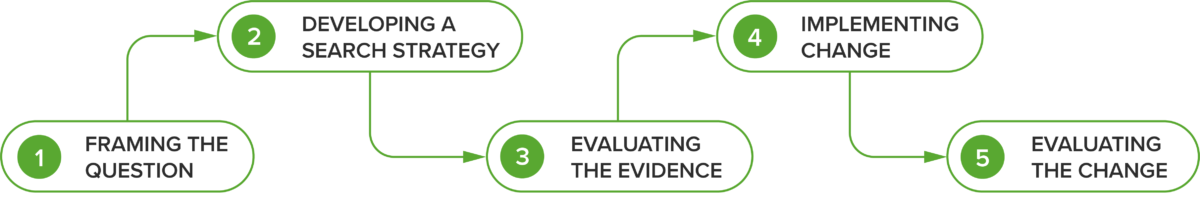

BEME is a term that featured prominently in the first BEME guide by Harden et al., which made the case for a shift from opinion-based teaching to an evidence-based approach in medical education and provided guiding steps on how educators can achieve this.(11,12) Reminiscent of the scientific process in evidence-based medicine, the five steps of BEME encourage educators and institutions to:

- frame the (research) question the way one would frame a scientific question, using Hammick’s participants, educational aspects, and expected outcomes as the framing model(12)

- design a search strategy for common bibliographic databases to find the most relevant research articles and evidence for the framed question(12)

- use the QUESTS criteria suggested by Haig and Dozier(13) to evaluate the quality and relevance of the evidence when an educator is investigating evidence to use in his or her classes – QUESTS stands for Quality (the type of evidence and strength of the studies), Utility (how useful the evidence is and how it can be adjusted to fit the context in question), Extent (the number of studies and their scope), Strength (how reliable the conclusions of those research articles are), Target (how similar the expectations in the studies are compared with the teacher’s), and Setting (how similar the setting of the research is to the teacher’s situation)

- implement the evidence in the classroom setting,(14) i.e., apply the evidence that the educator has identified to design his or her teaching strategies

- evaluate the outcome(14) so that the educator can make an objective decision on the final adoption of the technique. Publishing the results can help other educators in their teaching and thus should be considered as well.

The Five Steps of the Best-Evidence Medical Education Approach(11,12)

Translating cognitive science into medical education

A notable milestone is the advancement achieved by the combination of cognitive psychology and education. A grant awarded by the James S. McDonnell Foundation in 2002 to Henry L. Roediger III, Mark A. McDaniel, and nine other co-investigators kickstarted a ten-year collaboration between them that produced numerous research articles.(15) This fundamental work helped “translate cognitive science into educational science.” While it was not performed in the context of medical education, it informed and accelerated research on the topic within the medical education community, as is made evident by the numerous research papers in the past decade on the application of cognitive science techniques in medical education.

Ineffective Conventions vs. Evidence-Based Learning Principles

Why are evidence-based strategies still not widely accepted in medical education?

Effective, theory-driven, and evidence-based techniques are underutilized by both teachers and learners, yet popular techniques that have been proven to be ineffective are still commonly adopted.(16) When we think of medical education, some notable traditional teaching and learning methods come to mind: Large group passive lectures and rereading and cramming are just a few of these traditional techniques. These modalities, while beneficial in certain situations, have been proven to be suboptimal (e.g., passive vs active lecture,(17,18) massed vs spaced learning,(19) and re-studying vs spaced retrieval(16,20)).

Possible reasons for this situation include the overwhelming number of techniques available and a lack of exposure to effective strategies.(16) Often, students already understand which techniques are effective and which ones are not, but are not able to translate this understanding into real-world practice owing to their habit of cramming before exams.(21)

A practical insight included in Make It Stick, a well-referenced and highly readable book on the topic of effective learning, better illustrates why this problem of cramming persists among students.(15) A medical student interviewed by the authors suggested that some of these evidence-based strategies feel counterintuitive to students, giving the impression that their implementation could slow down the learning process. However, he had experienced better and more consistent results in his learning with a shift toward evidence-based techniques and recommended that, in order to better apply these, students needed to learn to “trust the process”.(15)

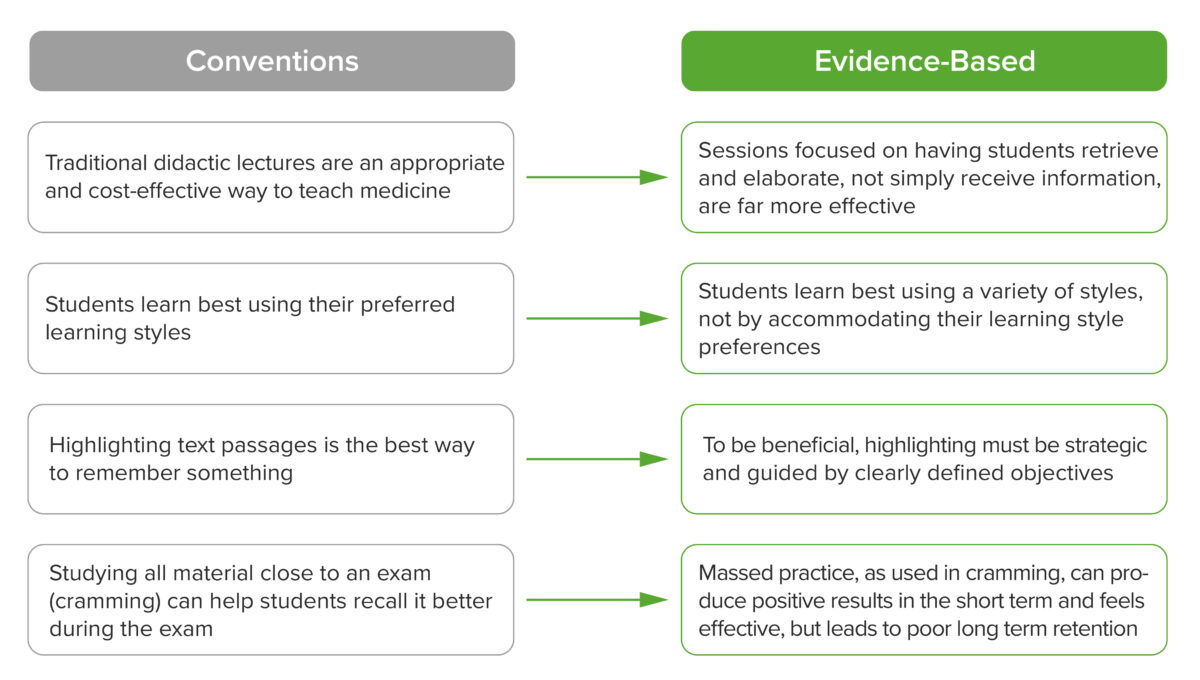

In the following section, four common misconceptions in medical education are examined to show ways to tackle them with the evidence-based approach previously discussed.

Ineffective Conventions in Learning vs. Evidence-based Learning Principles

Traditional lectures

The large-hall lecture has dominated education for centuries(22) owing to cost considerations (fewer staff members and separate classrooms required)(18) and its ability to convey large amounts of information to a large number of people and proven effectiveness in providing explanations in medicine.(23,24)

However, newer research has shown that an active component or complete replacement with active learning modalities allowed students to concentrate more easily, increase their participation, achieve a higher pass rate, and obtain better exam scores.(22,23) A multicenter study by Dash et al. found that a delegator teaching style, associated with promoting responsibility for learning among students, is increasingly preferred by teachers.(25) The challenge now is to bridge this preference gap and facilitate the process of shifting away from purely didactic lectures, which would most likely require collaboration at an institutional level.

Learning styles

Another ineffective convention is that of learning styles. It suggests that a student would learn better under certain conditions, using certain types of materials, being instructed in different styles, and/or utilizing certain types of mental activity (involving different levels of cognition).(26) Some examples of learning style models include the VARK model (visual, auditory, read/write, and kinesthetic), which divides styles based on the type of material that the learner is exposed to, and the Gregorc learning style model (abstract sequential, abstract random, concrete sequential, and concrete random) which divides it based on the sequence and type of material being presented.(27)

However, these models may actually limit a student’s potential by boxing him or her into one learning modality,(28) and there is a lack of methodologically sound evidence on their effectiveness.(26,29) Instead of focusing on students’ learning styles, it has been suggested that adapting teaching to a style appropriate for the content (30) and focusing on other proven evidence-based techniques could yield better learning outcomes.(26) Thus, while students will have learning preferences, moving beyond these preferences and using a variety of learning styles can lead to more effective learning.

Highlighting

Highlighting or marking is seen to be an easy, low-effort go-to studying technique that helps students learn better.(16,31) Some may mark very little, while others mark almost all their text.(16,32) In theory, the technique is based on a phenomenon called the “isolation effect,” which causes distinctly different, or differentiated, ideas to appear prominently in a person’s memory, allowing for better recall in the future.(16) Research initially found that highlighting does not produce a superior result over simple reading.(32,33)

However, when specific nuances in the research were considered, it showed that performance on questions pertaining to highlighted text was actually better and that a better outcome resulted when students actively highlighted text (i.e., they consciously thought about and chose what to highlight).(16) Overmarking is an excessive highlighting of text passages and is commonly seen in the textbooks of medical students. It is counterproductive because it reduces the distinction of the highlighted text and requires less cognitive processing by the student.(16) Considering these aspects, we can conclude that highlighting can still be an effective technique as long as the student uses it appropriately and only highlights objectively important parts of the text, a technique that can be strengthened by guidance and training.(16)

Massed practice

Massed practice is at the opposite end of the spectrum from spaced practice. It is a very popular, yet ineffective, technique that students often use to prepare for exams, concentrating their learning in short time spans with very few to no gaps between each study session.(16,19) Massed practice is also the technique used when students “cram” for exams. Students most likely cram due to the metacognitive bias that it produces (the false feeling of greater mastery over the material prior to the exam) and the marginally better performance in the short term with cramming.(34) They may also prefer it due to the false belief that cramming produces the same outcomes as other, more difficult techniques(16) or because it feels like it takes less time to study with this technique.(19)

Many studies have disproven these beliefs. One has shown that, while cramming may produce better outcomes initially, it is vastly outperformed when tested at longer intervals,(16) other studies have also generally found better long-term retention when students practice spaced learning.(19,35)

The Takeaway Message

When considering the relevance of basic sciences in medicine, it is clearly important as well that medical educators approach the education of future medical practitioners with an equally scientific lens. Incorporating the BEME approach, along with learning and cognitive science, into their teaching techniques will ensure that information is delivered effectively and common ineffective conventions are avoided. This will allow medical educators to reliably help their students (and their peers) to keep up with the exponential growth in medical knowledge and to practice high-quality continuing medical education in the long run. In subsequent articles in this series, we will discuss how science-based teaching strategies, such as spaced retrieval, interleaving, dual coding, and others, combined with the use of digital platforms, can support educators in this endeavor.

Would you like to learn more about this topic? Read the in-depth article, “History of Learning: From Theory to Evidence-Based Application in Medical Education,” in which the history of learning, different types of learning theories, ineffective conventions, and the evidence-based approach to tackle them are explored in greater detail.

Self-Quiz

(Please select all that apply)

1. Which of the following learning theories have implications on modern medical education?

a. Social Learning Theory

b. Constructivism

c. Cognitivism

d. Behaviorism

e. Structuralism

2. Which of the following is incorrect about the function of learning theories for medical educators?

a. It supports them in creating better learning objectives

b. It supports them in designing better evaluation strategies

c. It supports them in choosing one best theory to base their teaching on

d. It supports them in designing better instructional strategies

e. It allows them to combine different principles and implement them appropriately

3. Which of the following is part of the BEME approach?

a. Framing the research question with the PICO approach

b. Evaluating the evidence against the QUEST criteria

c. Implementing change in their classroom based on the found evidence

d. Developing a search strategy for bibliographic databases

e. Evaluating the change and publishing the results in a scientific journal

4. Which of the following statements are accurate?

a. All types of highlighting are an important and proven technique for learning

b. Traditional lectures are inferior as a teaching modality

c. Cramming is adopted by students because of metacognitive bias and a shorter time investment

d. Highlighting passages can be effective if done actively and selectively

e. Accommodating students’ learning style preferences is important

Correct answers: (1) all. (2) c. (3) b, c, d, e. (4) b, c, d.

Online Seminar

This second online seminar from Lecturio’s Durable Learning series focuses on prevailing misconceptions in the educational process and provides an overview of more effective evidence-based strategies. We hope this session will help you make the learning process more effective and efficient by using evidence-based learning strategies in your own educational institution.

Watch the seminar recording:

Would you like to learn more? Explore the Pulse Seminar Library.