Overview of Learning Science in Medical Education

Basic science is an integral part of a clinician’s journey toward becoming a skilled health care provider. Abraham Flexner, Ph.D., an education scholar from the turn of the century and author of The Flexner Report, famously argued that because basic science plays an important role in medical practice, this importance should also be reflected in medical training. Flexner’s belief forms the basis for his recommendation to incorporate an academic model into the former apprenticeship model that dominated medical education at the time.(1) A similar stance was argued in reverse order in a Lancet commentary by Filewod et al., which underlines that a clinical perspective can guide basic scientific research and create outcomes with direct relevance to the health of patients.(2) Understanding this, it stands to reason that the same attention should be afforded to the incorporation of learning and cognitive science in medical education itself.

Ever since it started gaining popularity in the 1950s, medical education research has always been influenced by current knowledge in the cognitive psychology domain. In the beginning, a behaviorism-dominated approach was more common, which was then followed around the 1970s by a rise in cognitive concepts such as memory, retention, and reasoning. By analyzing cognitive processes that delineate how the mind behaves when learning, researchers subsequently shaped instructional strategies, which allow us to advance further how we teach medicine.(3)

Medical education organizations, such as the Association for Medical Education in Europe, have taken this research even further by codifying existing learning theories to support educators in planning how they teach. Taylor and Hamdy outlined some existing theories that underpin adult learning, or andragogy, such as the instrumental, humanistic, transformative, social, and other theories. They postulate that these theories, including their subsequent interpretations, should closely influence the education of health professions, as it is believed that this could improve clinical learning and, presumably, outcomes of patients in clinical settings.(4)

Medical education is a continually evolving field. Evidence-based educational practices are becoming more widely known than ever before, and research in the domain is culminating in countless recommendations and guidelines. This is because medical education is still far from perfect, and among the many issues we face are the difficulties of long-term information retention or the lack of what we refer to as durable learning. Further research into evidence-based learning and teaching concepts is increasingly gaining importance, specifically with regard to a number of challenges faced by medical students nowadays.

Challenges Faced by Future Health Care Providers

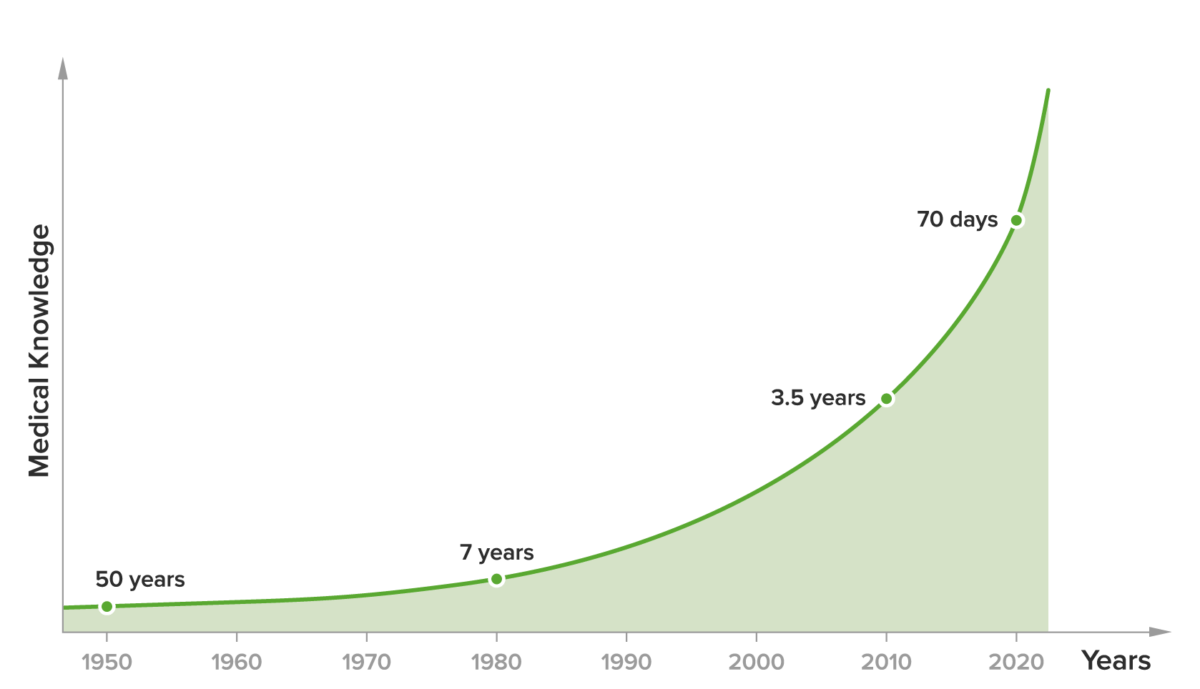

Studying medicine has always been a challenging feat, and studying medicine in the 21st century is even more demanding. One of the core problems is the huge amount of information that medical students (and physicians after they graduate) must retain. It is impossible to keep up with the rate at which the breadth of knowledge is expanding. Compared to a doubling time of medical knowledge of 50 years in 1950, 7 years in 1980, and 3.5 years in 2010, the current doubling time is approximately 70 days.(5) This exponential increase in the amount of medical knowledge can also result in “cognitive overload“ and negatively impact learning outcomes.(6)

Moreover, the duration of medical school ranges from 4 to 8 years, which makes it a challenge for students to learn and retain information from the basic sciences, then to apply it in a clinical setting, and become comfortable and confident enough to be competent physicians by the time they graduate, an issue which has been clearly demonstrated in the literature.(7–10)

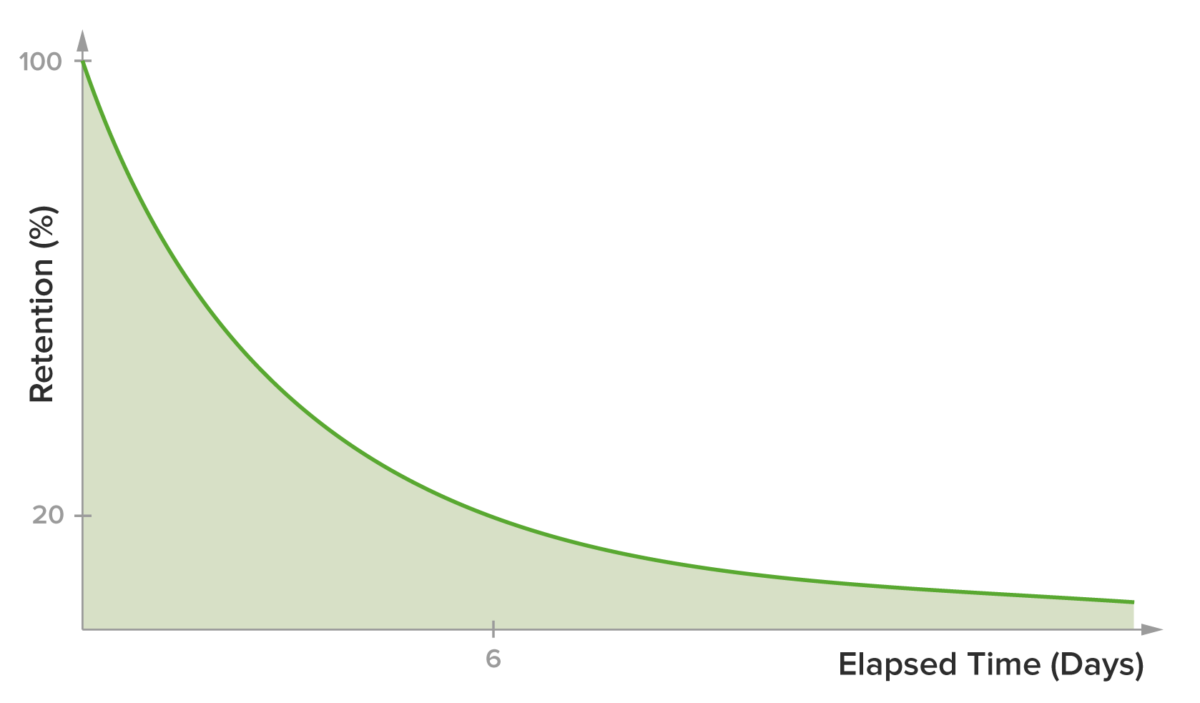

Another challenge with regard to durable learning comes in the form of medical students’ study methods: they predominantly rely on massed learning (or “cramming”).(11) This method feels like the easiest way to prepare for exams, which stems from the belief that information can be imprinted into a student’s long-term memory by massed practice. Cramming has even been shown to be a superior study strategy that boosts performance on some standardized exams, such as the USMLE®.(12) This massed practice, however, only results in established familiarity with the material and gives the student a false sense of confidence or mastery of the subject.(13) The information is easily forgotten(14) as demonstrated by Ebbinghaus’s forgetting curve.(15)

Figure 2. Typical Representation of the Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve (15)

Role of Medical Schools and Educators

A prominent factor that plays a role in the issue of long-term retention is the method employed by medical schools and educators. Many still rely on old-fashioned or traditional teaching methods, such as lectures (at up to 50% of schools in the US and Canada(16)), which have been shown to be less efficient than other methods.(17,18) While there are many factors that determine which teaching method is utilized, a crucial one is that educators rarely have proper background or training in education or instructional design.(19) Thus, being a good clinician alone does not always correlate with being a good educator.

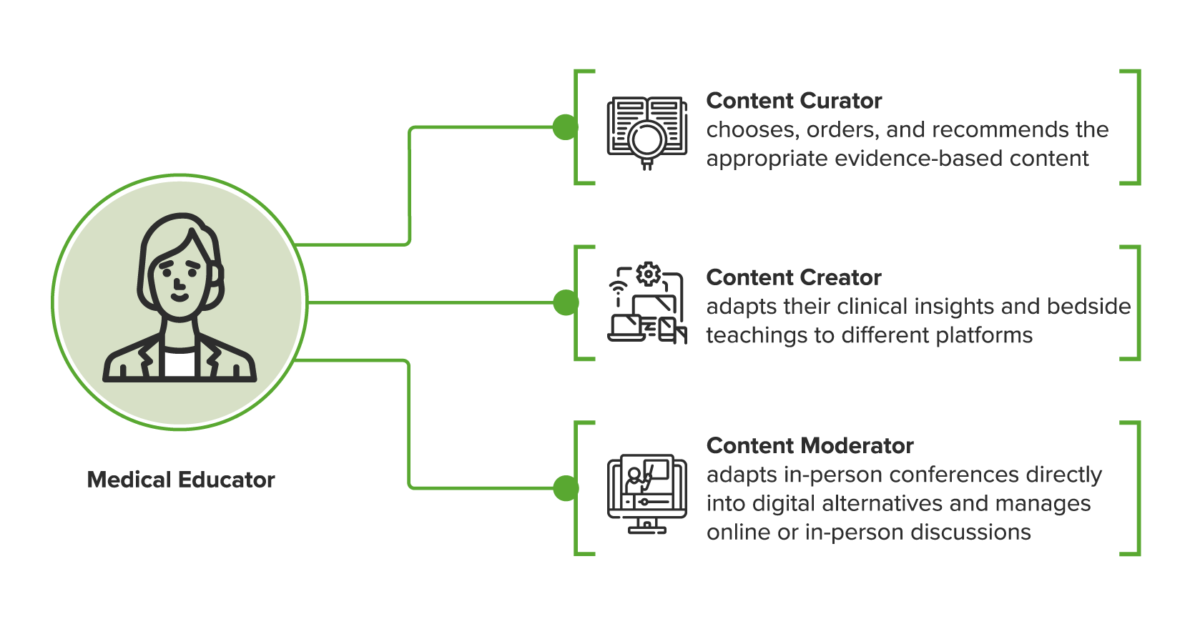

The role of medical educators has been changing for quite some time, partly as a response to the new challenges mentioned in this article. Moreover, 2020’s shift from offline cognitive apprenticeship models to online methods and digital tools has been a catalyst in this change. The roles that have been brought to the forefront of the field since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic include the requirement for educators and clinical experts to become content curators, creators, and moderators, specifically of online content. As content curators, educators must choose, order, and recommend the appropriate evidence-based content at the right time and place for their students. As content creators in the current age, they need to adapt their clinical insights and bedside teachings to different platforms (in the form of Twitter threads and short messages). Lastly, as moderators, they are required to adapt typical in-person conferences directly into digital alternatives (online webinars, classes, or problem-based learning (PBL) tutorials) by becoming proficient in the tools of these digital platforms and adept in managing online discussions, which present different and significant challenges than their offline counterparts.(20)

Figure 3. The Evolving Role of Medical Educators (20)

Even in the post-pandemic era, it will be important that medical educators act more in the role of coaches than lecturers, at least when acting in a “live” capacity.(21,22) This allows for much better use of their time and provides students with the opportunity to be initially exposed to new material using the most effective tools available.(23) This approach has been referred to as being a “guide on the side” rather than a “sage on the stage.”(24) While a teacher’s active delivery of content can still be a valuable tool, it is far more efficient and effective to have this recorded in advance and delivered in an optimum fashion according to a given student’s needs and utilizing techniques validated by learning science.(23)

Implementing Better Learning Strategies

The foundational knowledge that medical students are supposed to acquire in their first years is an essential building block upon which future clinical knowledge and reasoning are built. Students will base their learning on this until they graduate and become practicing physicians. Thus, the lack of durable learning poses a challenge to medical education that impacts students and junior doctors around the globe.(9)

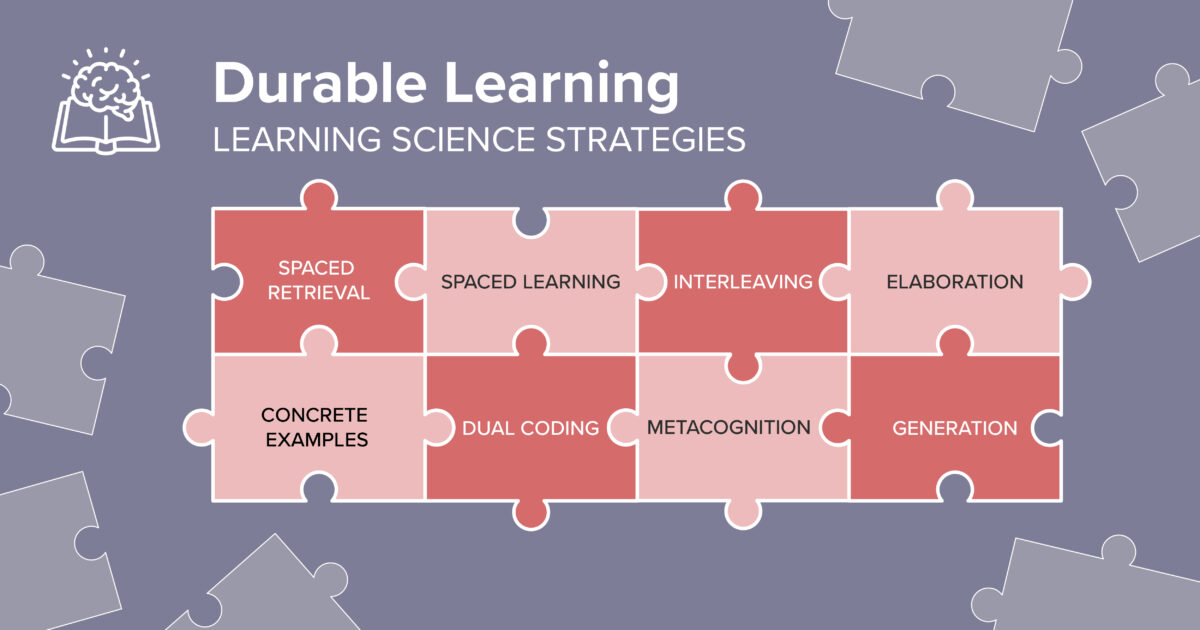

Considering that fact, it is important that current and projected challenges in medical education be solved by incorporating learning and cognitive science in the design of teaching and evaluation strategies for medical students. These strategies can be applied either as a standalone strategy or in combination with one another. Some of the aforementioned strategies include:

- Spaced Retrieval

- Spaced Learning

- Interleaving

- Dual Coding

- Concrete Examples

- Metacognition

- Elaboration

- Generation

While there remains much room for improvement on different levels, it is essential for educators and curriculum designers to create and maintain an educational system that incorporates these principles of learning science.

The adoption of digital platforms developed mainly as a response to new challenges that all students, including medical students, face as a result of the ever-changing landscape of global knowledge. The issue of knowledge retention, combined with the increase in the speed of growth for existing knowledge on any given subject and the advent of digital native learners, has made digital learning an attractive solution to the imperative of lifelong learning.(25) Finally, digital platforms provide means for students to quickly and continually acquire ever-changing knowledge. As Bonk puts it, it essentially allows them “to learn anything, from anyone, at any time.”(25,26)

In subsequent articles in this series, we will discuss how science-based teaching strategies, combined with the use of digital platforms, can increase the knowledge acquisition and retention rates of students in this day and age, without sacrificing the currently adopted ap