Cognitive Foundations

Rather than just using assessments to determine if learning has occurred, assessments can also be used to support learning. Test-enhanced learning (TEL) is an approach that uses assessments to improve recall and retention of learning. A BEME review of TEL in medical professions found that the use of assessment to support learning was highly effective across various learners and assessment types (2).

The use of short, spaced assessments promotes retrieval practice. Retrieval practice has been shown to improve the learner’s ability to recall information later. Additionally, effortful recall has been shown to increase the retention and transfer of learning. Assessments that are spaced and promote effortful recall such as frequent context rich multiple-choice questions (MCQ), short answer questions, and open ended responses foster more effective learning than a single exam or less effective study practices such as rereading.

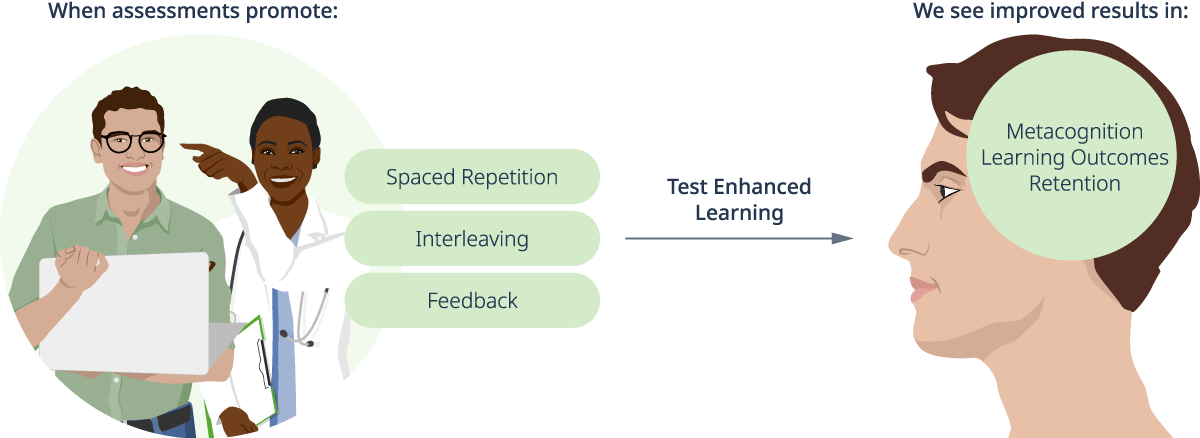

The traditional use of summative assessments, evaluating learning at the end of instruction, determines if learning has occurred but does little to provide corrective feedback or support learning. Frequent low-stakes assessments, often called formative assessments, can instead be used to scaffold skills and encourage spaced repetition and interleaving. Studies have shown that structuring quizzes throughout the term to use spaced repetition and interleaving can improve metacognition and the retention of knowledge over traditionally structured quizzes (3). When providing formative assessments, feedback is an essential part of the TEL approach and is recommended at a minimum as giving the correct answers and rationale (2,4). Feedback supports learning by correcting misconceptions and reinforcing the correct answers and reasoning.

Test-enhanced learning uses concepts such as spaced repetition, interleaving, and appropriate feedback to improve metacognition, learning outcomes, and retention.

Designing Assessments

Poorly-designed assessments do little to gauge student learning and often frustrate both students and faculty. Well-designed assessments should support the learning process and aid in decisions such as determining completion, licensure, or the need for remediation.

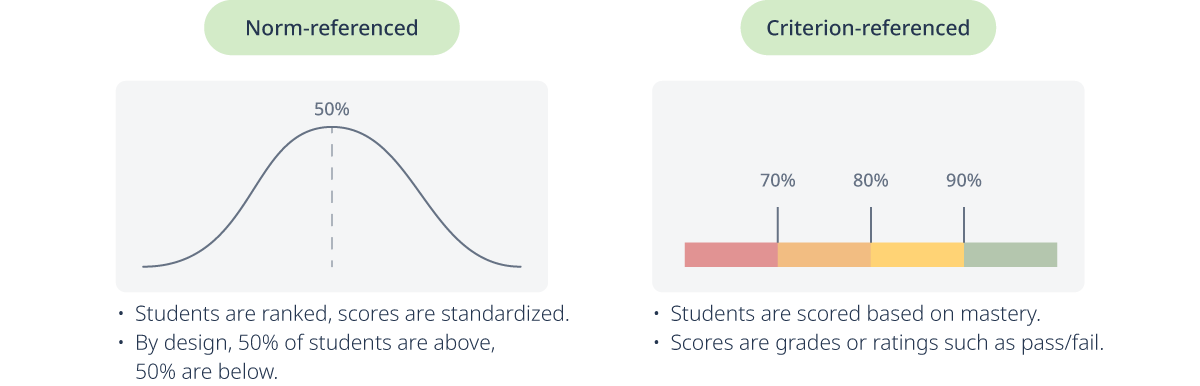

Assessments can be divided into two broad categories: norm-referenced and criterion-referenced. Norm-referenced tests give a rank or placement by comparing students to a group of representative students called a norming sample (5). These types of tests yield percentile rank and standardized scores, such as those given by the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT), Medical College Admission Test (MCAT), or intelligence (IQ) tests. Criterion-referenced tests score students based on their proficiency or mastery of a set of skills (5). They are based on a predetermined set of criteria and result in a percentile grade or pass/fail determination. Criterion-referenced tests are most commonly used in the classroom and may also include licensure tests such as the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) and the National Council Licensure Examination (NCLEX) in the US or the “International Foundations of Medicine” (IFOM) exam. Many countries have their own versions of these licensing exams. This article will focus on criterion-referenced assessments since they are most typically used in classrooms.

Norm-referenced and criterion-referenced are two broad categories of assessments.

Planning Assessments

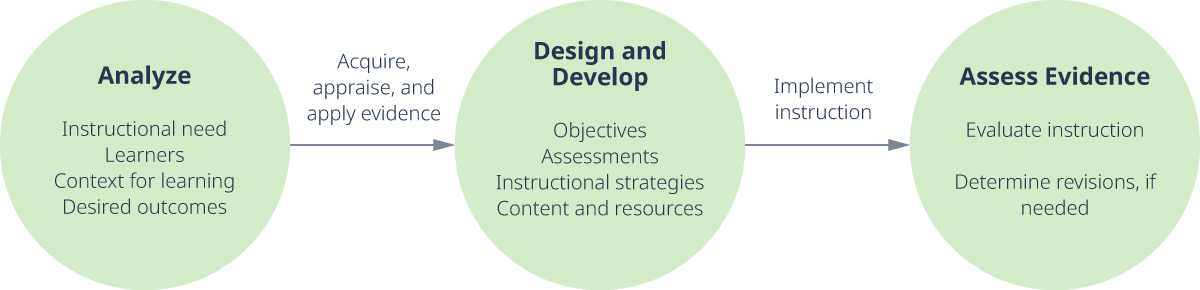

Recalling principles from instructional design, assessments should be a planned component of course design, aligned with both objectives and content. Course design begins with determining the need for instruction and analyzing both the learners and the context for learning. From here, the instructional designer and/or faculty member acquires and appraises available educational evidence related to the identified instructional needs. This phase then informs the development of objectives, which in turn drives the determination of assessments, instructional strategy, and content. After implementing instruction, the results are assessed by evaluating instruction and determining the need for revisions.

Planning assessments as part of the instructional design process

The need for instruction, the learners, the context for learning, and the objectives all help determine the need for assessment such as:

- The format in which will learners be assessed, e.g, online, on paper, or observed in a clinical setting.

- The number of assessments that will be given and when.

- The type of feedback needed to help the students develop the necessary skills, knowledge, and dispositions.

Once these are established, the assessments can be aligned to the objectives based on the domain of learning and the level of desired performance (e.g. Bloom’s revised taxonomy).

Aligning Assessments

In our previous article, we addressed the alignment of learning objectives to assessment and instruction, especially with regard to the domains of learning and the action verbs used in the objectives. For example, an objective that involves the affective domain, such as “Students will be able to communicate clearly and compassionately with families of pediatric patients” would be best assessed by observation in an authentic setting using a rubric that clearly defines the expectations for communication. However, an objective in the cognitive domain such as “Students will identify the functions of the ventricles of the brain” would be best assessed using objective items such as MCQ or short answer questions.

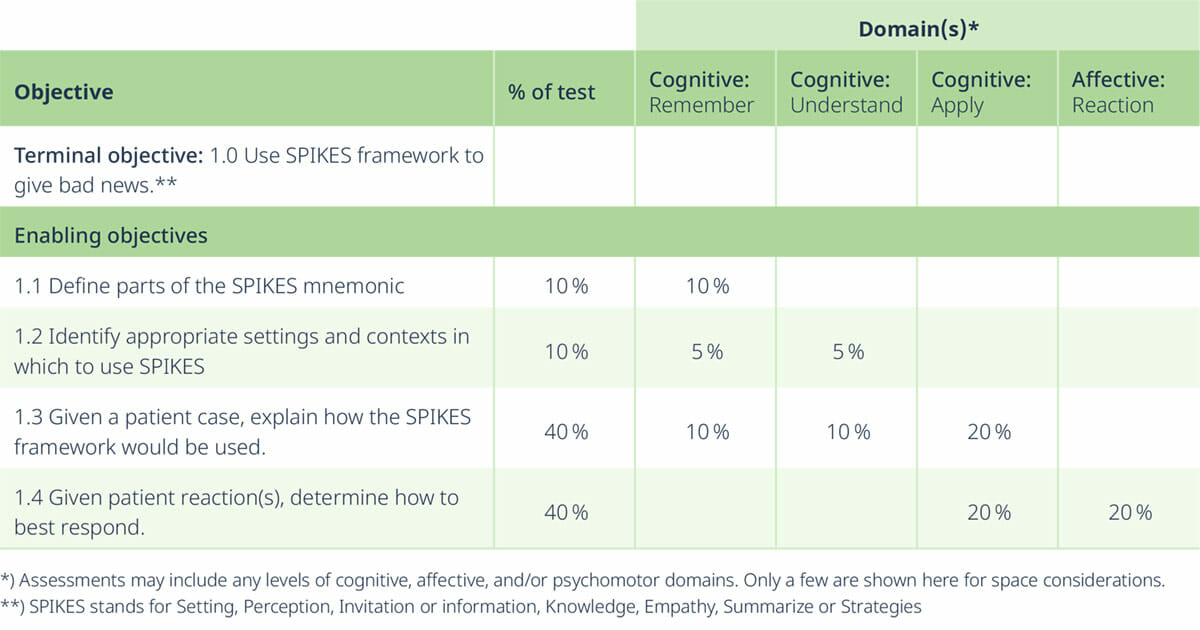

Once the objectives are established, a test blueprint can be developed to ensure coverage and alignment of the assessment with the objectives (7). For example, if students are told an exam will cover learning objectives from Chapters 1-3 but only questions from Chapter 2 are given, the test has poor coverage. If questions from Chapter 4 appear, the test has poor alignment. Material may not be assessed equally but should reflect the amount of time spent during instruction, corresponding to the relative importance of the topic (7). Test blueprints can map the objectives, domains of learning, and weight of the topic on an exam (number of questions, point value, or percentage).

Table 1: Sample test blueprint

A test blueprint can help educators integrate technology by using test banks or learning management system (LMS) features that allow educators to create assessments by choosing topics from categories that align with learning objectives. Test bank questions can be chosen quickly and efficiently from the appropriate categories with point values that are reflected in the test blueprint. To help ensure academic integrity, some test banks will automatically vary questions while other platforms such as Canvas LMS give options to vary questions by allowing question groups that choose from a pool of available questions, e.g. “select 5 of 12.” The instructor can set these question groups to align with objectives and allow the LMS or test bank to choose a unique set of aligned questions for each student. Selecting from a test bank or question group can also help ensure exam integrity by allowing different but effectively equivalent exams to be delivered simultaneously among students in the same class, minimizing the chance for examination improprieties, especially when students are being examined from remote locations.

Validity and Reliability

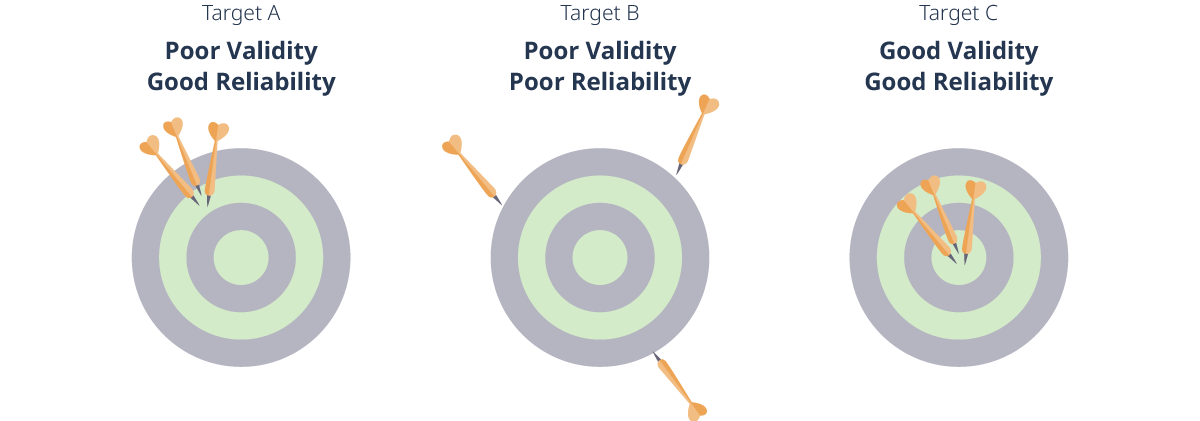

Validity and reliability are two ways to evaluate assessments. Validity refers to the degree to which the assessment measures what it intends to measure while reliability refers to the consistency with which an assessment measures (5).

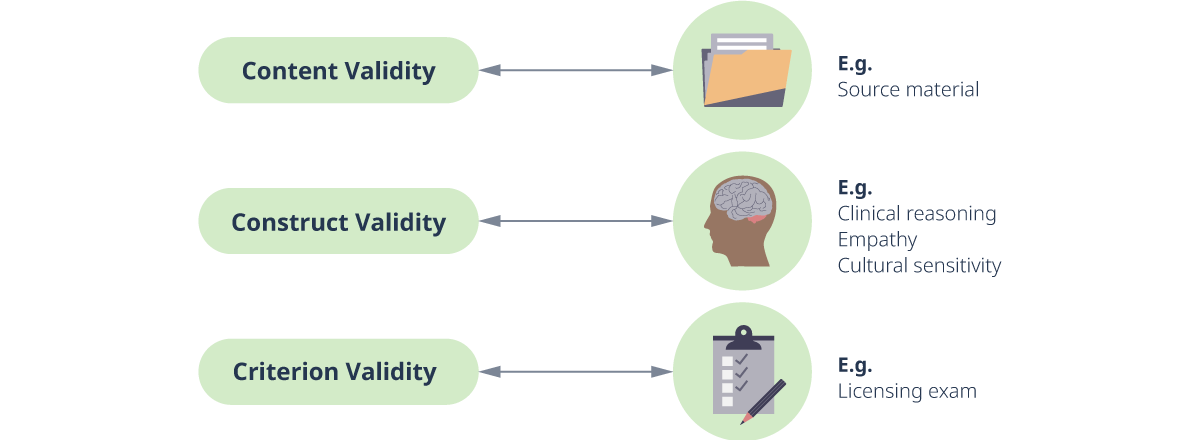

For example, content validity analyzes if a test measures the intended content. Does a project on diseased states of the kidney accurately measure a student’s knowledge of the kidney or something else, such as their computer skills (3)? Test blueprints strengthen content validity by ensuring test items align with objectives.

Criterion validity determines whether the assessment correlates with an external criteria. This can be concurrent, i.e. does the exam correlate well with another exam such as the USMLE or NCLEX, or predictive, i.e. does performance on this exam correlate with future behavior, such as performance in a clinical setting?

Construct validity determines whether an assessment measures a given construct (e.g. achievement or clinical reasoning) as supported by a rationale or theory.

Some argue content validity is the most important type of validity for measure of academic achievement (7) while others claim construct validity is the primary, unifying type of validity (9,10).

Content, construct, and criterion validity with examples.

Reliability refers to the consistency of a test to yield the same or nearly same results over multiple administrations assuming the trait has not changed (5). For example, one would expect a student to have similar scores on an identical exam taken two days apart assuming all other conditions remain the same. Reliability can be improved by using objective assessments (e.g. MCQ) and for subjective assessments, the use of rubrics and multiple trained raters can increase consistency.

Reliability and validity.

Evaluating Assessments and Instruction

Not only do assessments provide feedback on student performance, but analyzing assessment results can provide valuable information about the course instruction and the assessment itself. While calculating the statistics can be somewhat cumbersome, most LMS and platforms give some forms of item analysis such as the mean, item difficulty, item discrimination, and reliability. Item difficulty is a measure of how many people got an item correct. For example, a score of .65 means 65% of respondents got that question correct. A lower score means fewer students were able to correctly respond to the question. Item discrimination is a measure of whether examinee responses on that item reflect their overall score, i.e. whether high-scoring students get the question correct while low-scoring students do not. Item discrimination scores range from -1 to 1 where negative values indicate poor discrimination that actually detract from the validity of the test, while .40 and above have excellent discrimination (11). Reliability values such as Cronbach’s alpha (a measure of consistency or reliability) should ideally be higher than .90 for high stakes or decision-making tests, while .70 and above may be more acceptable and feasible for formative or performance assessments (12).

Care should be taken in applying these statistics to results from a single classroom on a criterion-referenced assessment. For example, a talented group with effective instruction may score consistently well versus a more heterogeneous group, but examining these results and identifying extremes in the different measurements may also show points of concern with test construction or instruction. Items with very high (near 0) or very low difficulty (near 1) should be examined to see if the question is too easy or faulty. Items with very low discrimination (<0.15) should be reviewed and potentially eliminated. If a review of the items indicate no apparent issues with question writing but concerns about difficulty or discrimination remain, the instruction should be examined to ensure that the question aligns with the objectives and content. Prior to instruction, a pre-test can provide data for examining assessment items. Item difficulty should rate high (or at least higher) in the pre-test group, and student answers prior to instruction should be distributed equally among distractors (11).

Practical Implications in Medical Education

With clearly defined objectives written and alignment ensured with a test blueprint, the next challenge for educators is writing the assessment. A well-written assessment helps increase validity by ensuring students are being assessed on their knowledge of the content, not on their ability (or inability) to understand poorly-worded questions or unclear tasks.

Best Practices by Type of Assessment

Multiple Choice Questions

MCQ, most typically in the form of single-best option (SBO) questions, are often favored for the ability to cover large amounts of material in a short amount of time, combined with ease of writing and grading. MCQs can also be integrated with technology and automated grading which makes them a favorite option for formative assessments. Well-written MCQ can also have high reliability as well as diagnostic capabilities. While MCQ questions can be used to test simple recall, they can also be used to test higher-order skills by adding context-rich scenarios involving clinical or laboratory cases (13,14).

Some key points in writing MCQ:

- The stem (the first part of the question) should fully formulate the problem or question. A student should be able to formulate the correct answer before viewing the responses (5,15).

- The responses should all grammatically match the stem, be homogenous (e.g. all diseases or all tests), and be kept as short as possible (5,15).

- The detractors (wrong answers) should be plausible to an uninformed person but not arguably correct (5).

- The options “all of the above” and “none of the above” should be used sparingly (5).

- Negative phrasing should be avoided but when used, the negative (e.g. “not”) should be bold and/or capitalized to ensure it is noticed (5).

- Avoid extreme statements such as always or never (16).

- Questions that are context-rich and include clinical information aid in assessing higher order skills and transfer of learning (13,14,16).

- When creating context-rich questions, put all relevant clinical information first and avoid any ambiguity (16)

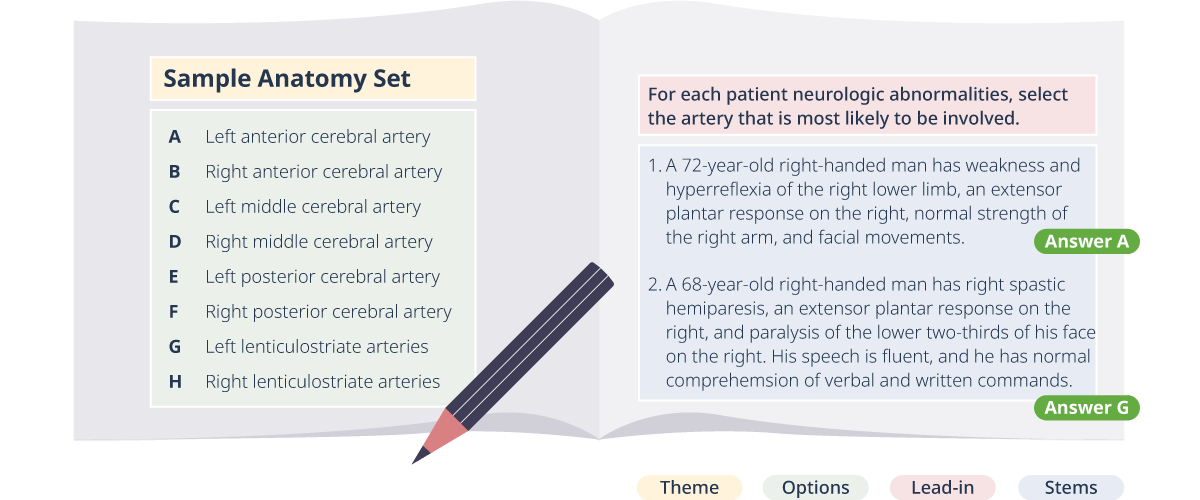

Most MCQ are single-best option questions, but extended matching questions (EMQs) can have SBO or multiple answer options. EMQ have many of the same features of MCQs such as containing homogeneous short options and a fully formed long stem. One format used by the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) incorporates patient vignettes into the following structure:

- Theme

- Options list

- Lead-in statement

- At least two item stems (may be SBO or multiple options)

The options list is homogenous with 5-20 items that fit the theme. The lead-in statement gives a short description of the patient type and the situation (anatomy, disease, test, etc). The item stem gives the full patient description that the student will use to answer the lead-in statement.

Sample EMQ set showing the theme, options, lead-in, and stems.

EMQ allow for patient vignettes, grounding questions in authentic clinical context and more options, which can help avoid cueing, in which students can identify the answer from the options without being able to recall the answer independently.

Open-Ended Response Types

While MCQ make up a large portion of assessment for healthcare education, other types of assessment are necessary to determine a students’ full range of skills, knowledge, and dispositions. Assessments such as open-ended questions, essays, and oral exams allow for examiners to assess students for their ability to communicate knowledge professionally, display clinical decision-making and reasoning skills, and effectively synthesize and report written information. Concerns about reliability and validity should be carefully addressed with these formats.

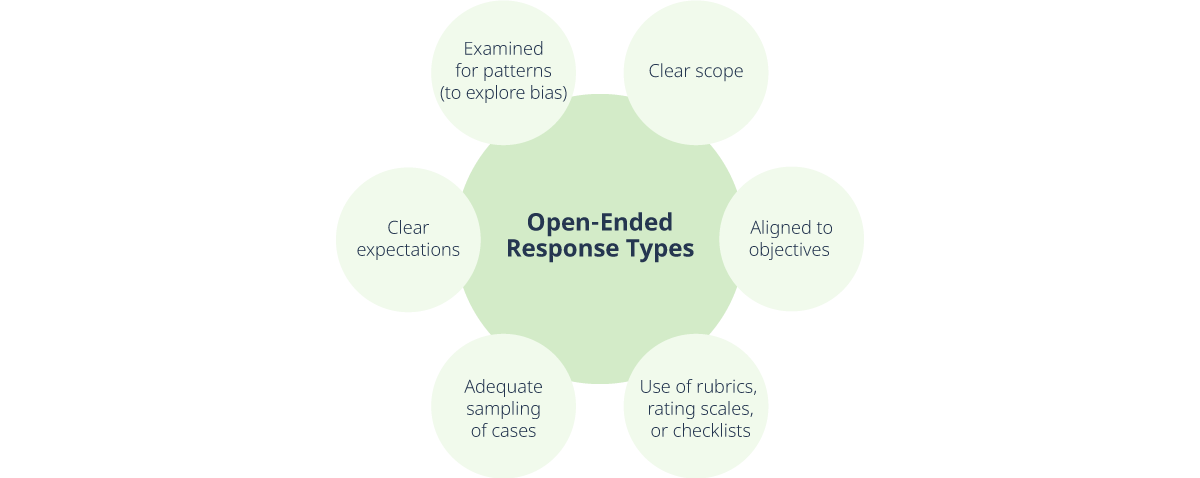

Best practices in implementing open-ended responses

Best practices for open-ended response items:

- Questions should be carefully formulated to make clear to the student the depth and breadth expected in their response. For example, instead of “Discuss causes of renal failure” which is vast and vague, be specific about what is expected such as “Compare and contrast 3 categories of acute renal failure including symptoms and causes.”

- Questions should be aligned to objectives to ensure content validity (e.g. discuss, compare, synthesize). In the case of summative or program-wide assessments where course objectives may not apply, the criteria should be established by a panel of experts based on professional practice (17).

- Rubrics, rating scales, or checklists (See Appendix) should be developed to ensure consistency of grading and reduce bias (5,17). When multiple raters are used, they should be trained for consistency among raters and groups (17).

- For oral assessments, an adequate sampling of cases should be used to ensure sufficient depth and breadth.

- If writing or oral skills will be assessed, the expectations should be clear to the student prior to assessment. If the exam is written or oral but assesses content and not presentation skills, care should be taken to focus the assessment criteria on that content and not on the learner’s language or writing skills. Extraneous skills, when explicitly expected, should only be assessed to the extent needed for professional practice (17).

- After assessments are complete, exam items should be examined for patterns in ratings by examiners and variations in scoring by sub-groups to explore potential bias (17).

Performance-Based Assessments

Performance-based assessments can take the form of simulations (including standardized patients), clinical observations, mini-clinical evaluation exercises (mCEX), or objective-structured clinical examinations (OSCEs). Performance assessments allow for assessing clinical competency by observing skill and behaviors in varying levels of authenticity. Performance-based assessments are a powerful means to assess many skills across all three domains of learning – cognitive, affective, and psychomotor.

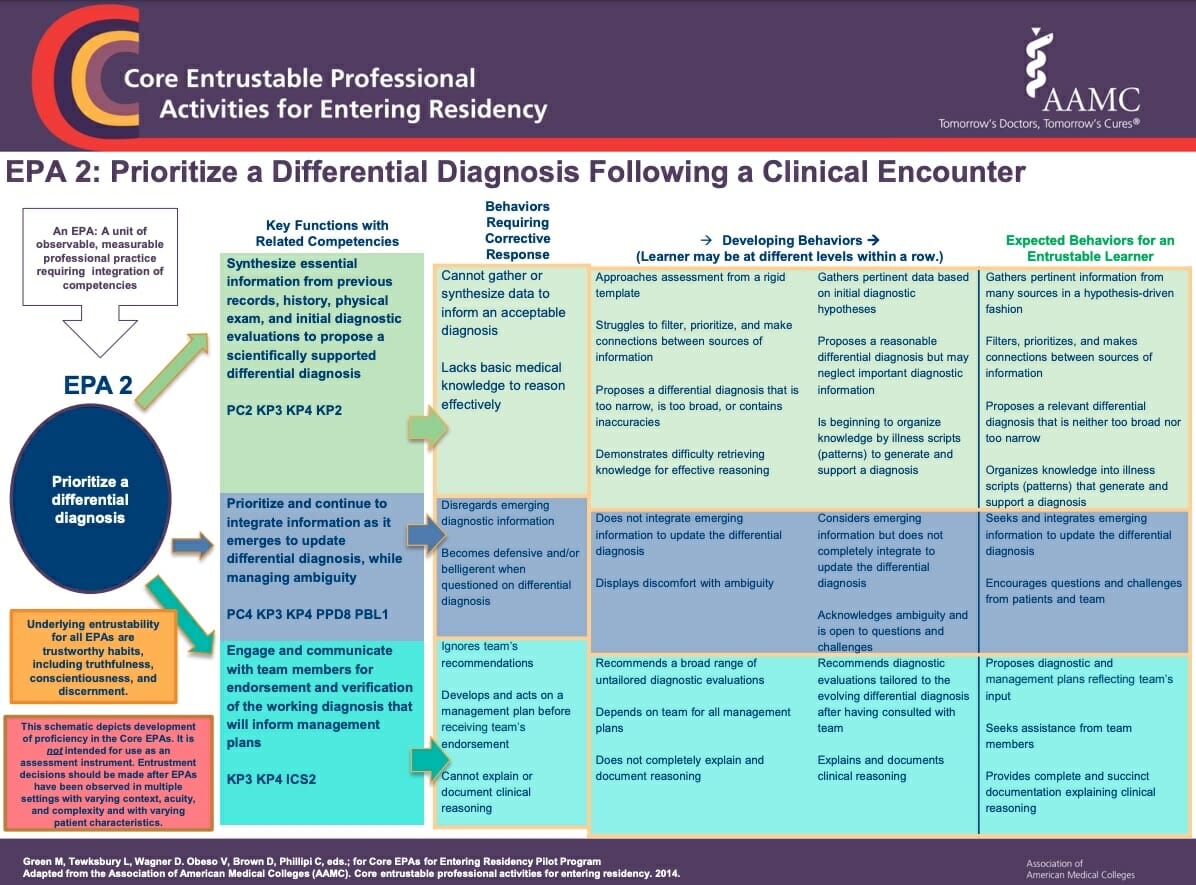

To further the development and assessment of performance-based skills, the Association of American Medical College (AAMC) has developed guidelines for Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) “that include 13 activities that all medical students should be able to perform upon entering residency” (18). These can be used to develop competency-based objectives and guide effective clinical assessments. For more information on EPAs, the full and abridged EPA toolkit can be found on the AAMC website and a practical “Twelve Tips” guide to implementation can be found in Medical Teacher (19).

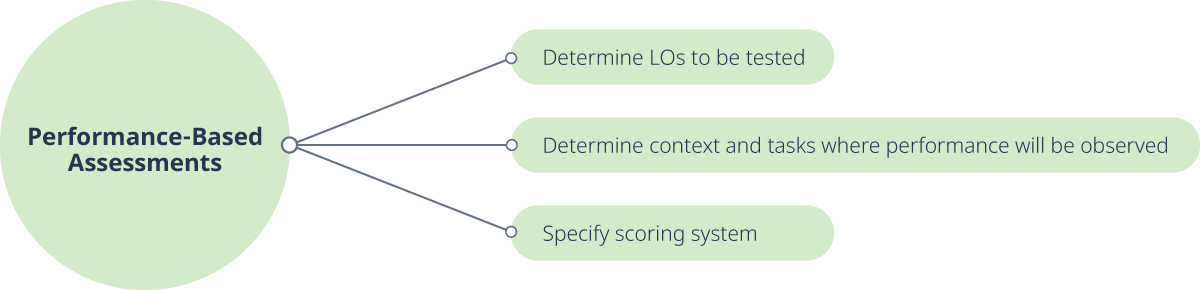

To develop performance-based assessments:

- Determine which learning objectives will be tested using performance-based assessments (5). For the cognitive domain, will students be assessed on skills related to acquiring information or skills related to organizing and applying information? For the affective and psychomotor domains, what observable evidence will be used to determine that students have obtained the desired skills, knowledge, and dispositions? Create a test blueprint to ensure alignment between objectives, content, and performance assessments (1).

- Determine the contexts and tasks in which the performance will be observed (5). Some assessments will be “snapshots” of skills at a particular time such as OSCE and mini-CEX. Some assessments will span a period of time such as portfolios and 360° evaluations (1).

- Specify scoring system(s) (5): rubrics, checklists, and/or rating scales (see Appendix). Input from multiple examiners, especially if trained, increases reliability of scores (1). The use of existing rubrics and guides can increase construct and criterion validity, e.g. use of Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) toolkit (18), OSCE checklists, and/or mini-CEX assessment forms.

Performance-based assessments

Recommendations

Instructor Perspective

Harness the power of technology. MCQ and EMQ can be delivered in online quizzes that are self-grading to provide immediate feedback to learners. Structuring these quizzes to be spaced and interleaved throughout the term can provide additional benefits for increased learning, retention, and metacognition in students (3). Using technology allows for more frequent feedback without adding undue burden to educators for grading or using precious class time.

Use multiple assessment types for both formative and summative assessments. Each assessment type has strengths and weaknesses. By using multiple types in formative assessments, students are provided with diverse feedback about their performance and progress. By using multiple types of assessment in high-stakes summative assessments, potential issues of validity and reliability found in a single form or instance of assessment can be mitigated and allows for a more holistic view of the students’ progress and abilities.

Use a variety of feedback given over time, especially for formative assessments. While self-assessment and peer review often lack reliability, when used with rubrics and checklists for low-stakes or no-stakes assessments, they can provide valuable feedback to students on their progress. Similarly, there is some evidence that delayed feedback, given after the assessment period, may be more effective to high-performing students, while immediate corrective feedback may be more effective with lower performing or less confident students (20). Frequent feedback to students allows them to track their progress and identify areas in need of remediation before high-stakes testing occurs.

Analyze data from formative feedback to provide evaluation of instruction and course design to help identify areas in need of improvement or revision. Students may need immediate remediation to meet course objectives, and instructors should use feedback to inform the potential revision of ineffective course elements for future instruction. When assessments are used in a formative way prior to class, the results of these assessments can be used to help teachers focus their in-class time on more challenging areas.

Student Perspective

- Use the objectives to help you plan and prioritize your studying.

- Look at the syllabus for information about the number and type(s) of assessments planned. If not specific, ask your instructor.

- Don’t just study facts: be ready to apply what you know to clinical cases, even for MCQ tests. Consider using active study habits like creating graphic organizers, making concept maps, and using case studies rather than rereading.

- For performance exams, ask for the rubric, rating scales, or checklist that will be used, if available. If it’s not available, look online for similar topics that may be found in OSCEs or EPAs.

Reflection Questions

(Select all that apply.)

1. Assessments can be used for what purposes?

a. To measure learning that has happened

b. To reinforce learning

c. To measure student progress

d. To motivate students

2. In what ways can content validity be increased?

a. Comparing the content with a licensing exam

b. Using a test blueprint

c. Ensuring alignment with objectives

d. Reviewing test items with very low discrimination or very high difficulty

3. What are some “best practices” in writing MCQ?

a. Have plausible but not arguably correct distractors

b. Using strong words like “always” and “never”.

c. Have a clear and complete stem.

d. Use clinical cases whenever possible

4. When reviewing assessments, what are some warning signs educators should look for?

a. Items that are too easy or too hard

b. Items with high discrimination

c. Sub-groups (such as race, language, or gender) performing equally on items

d. Evidence of bias or inconsistencies among evaluators

Answers: (1) a,b,c,d. (2) b,c,d. (3) a,c,d. (4) a,d.

Appendix

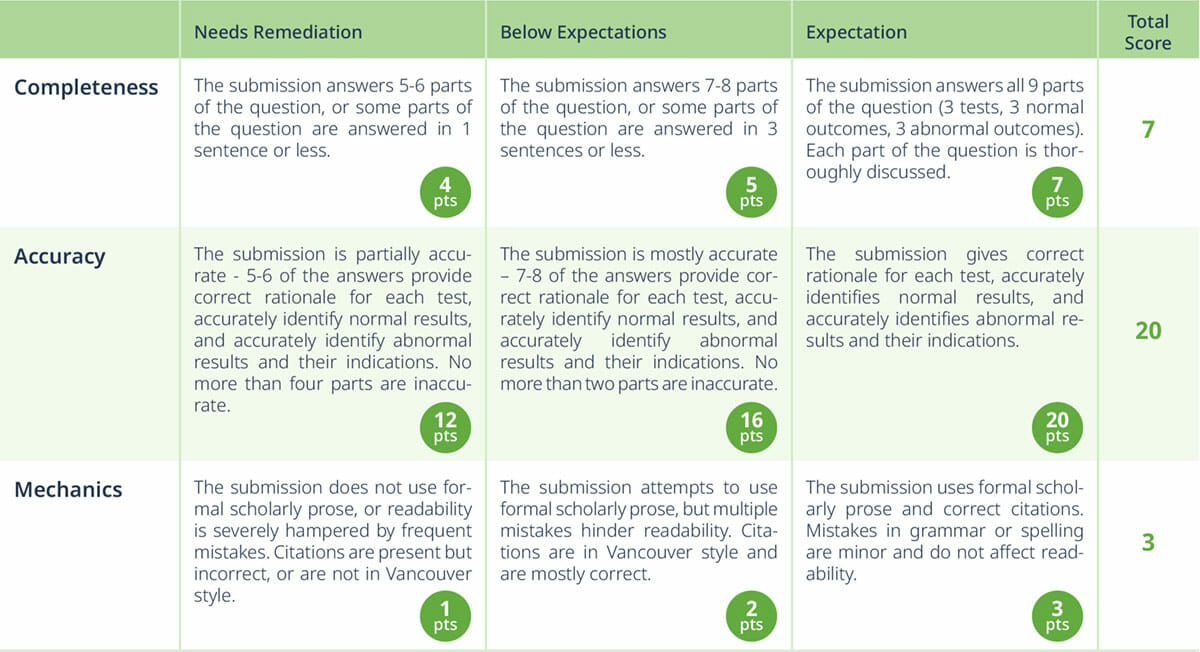

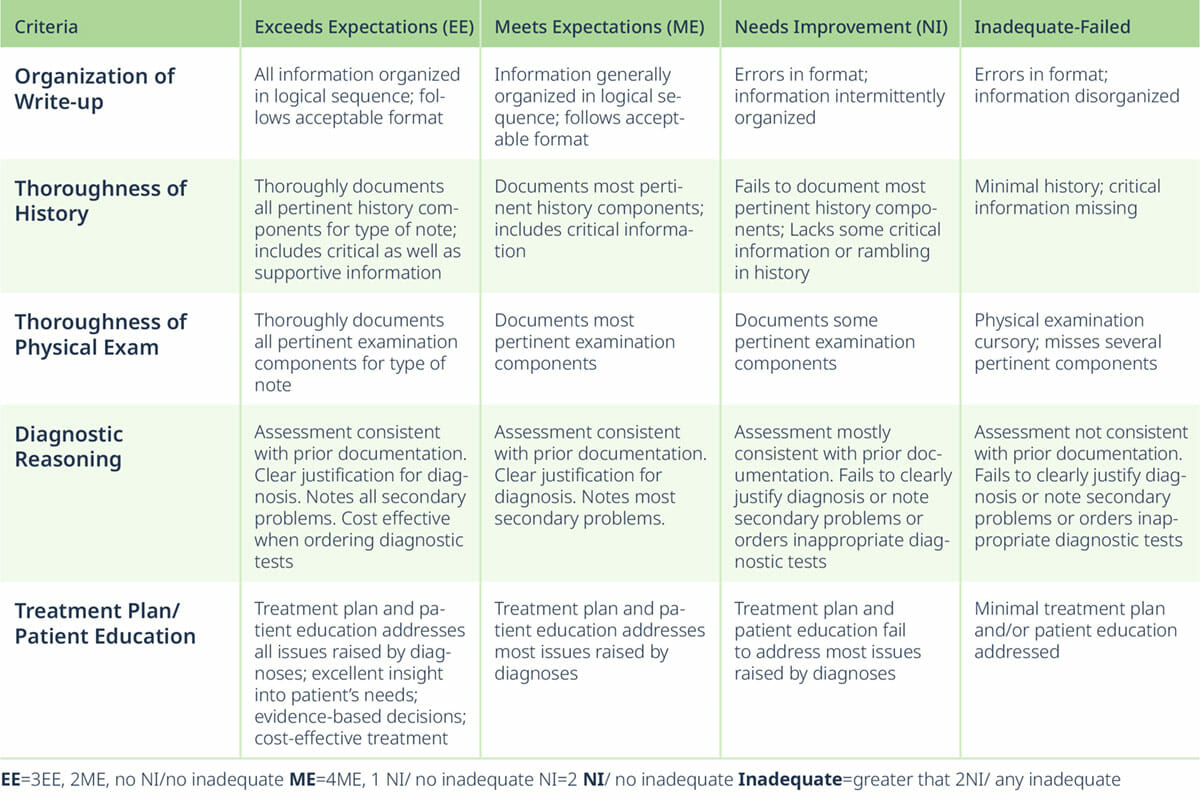

Sample Clinical Rubric

Modified from Florida International University source document (21)

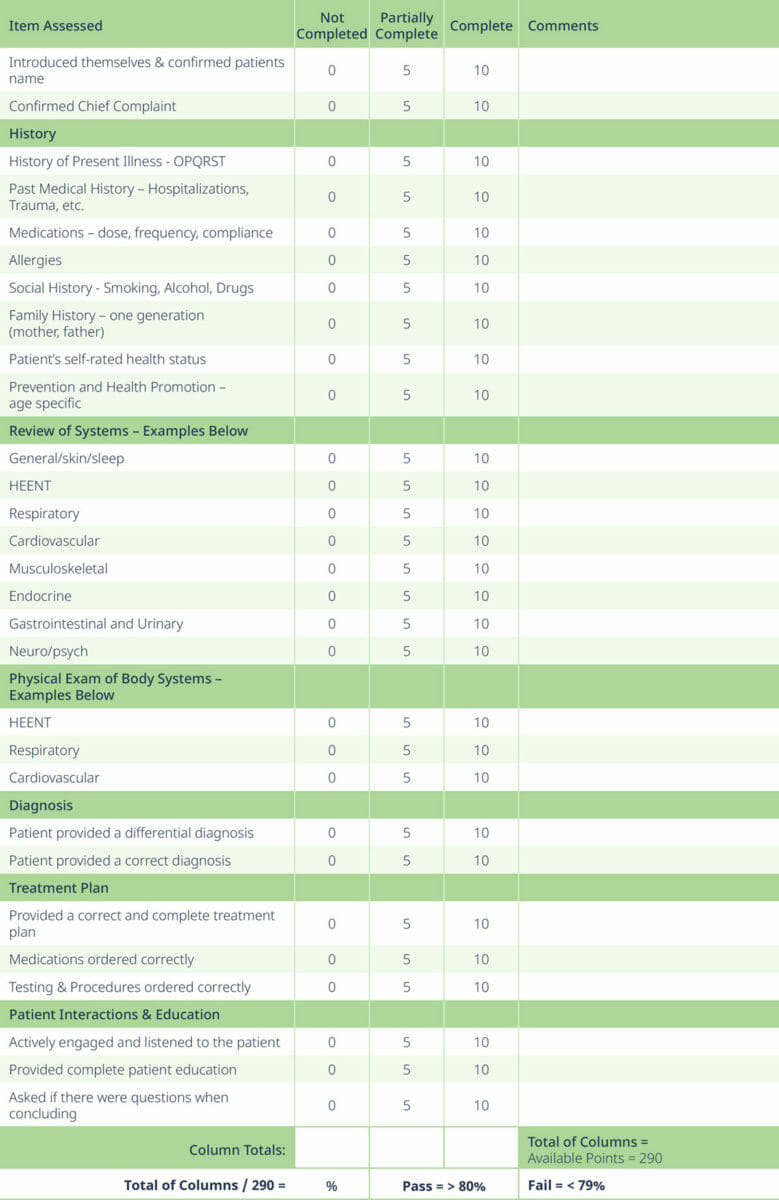

Sample OSCE Grading Rubric

Instructions: Circle the score for each row, add up the total points for each column, add all the column totals for the final score, divide by total possible number of points for overall percentage. Pass = 80% or greater.

Modified from University of Arizona College of Nursing source document (22)

Sample EPA Toolkit

Sample page from AAMC EPA Toolkit (18)