Anal fistulas are abnormal communications between the anorectal lumen and another body structure, often to the skin. Anal fistulas often occur due to extension of anal abscesses but are also associated with specific diseases such as Crohn's disease. Symptoms include pain or irritation around the anus; abnormal discharge or purulent drainage; and swelling, redness, or fever if an abscess is present. Management is primarily surgical, with fistulotomy, but can include antibiotics if infection is present. Complications after surgery include recurrence and incontinence.

Last updated: Dec 15, 2025

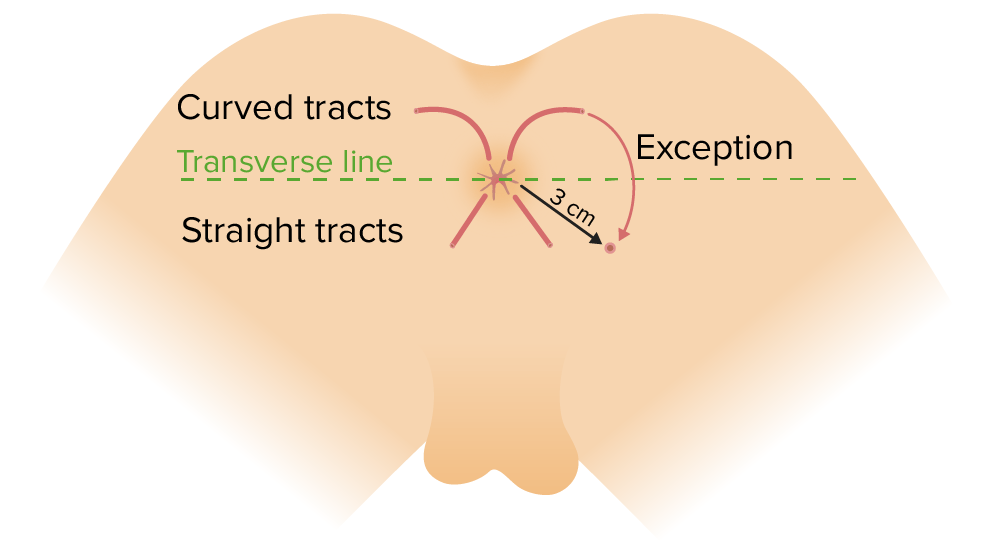

Goodsall rule:

Fistulas originating anterior to the transverse line through the anus will have a straight course and exit anteriorly (an exception to this rule includes anterior openings > 3 cm from the anal verge). Fistulas originating posterior to the transverse line will begin in the midline and have a curved tract.

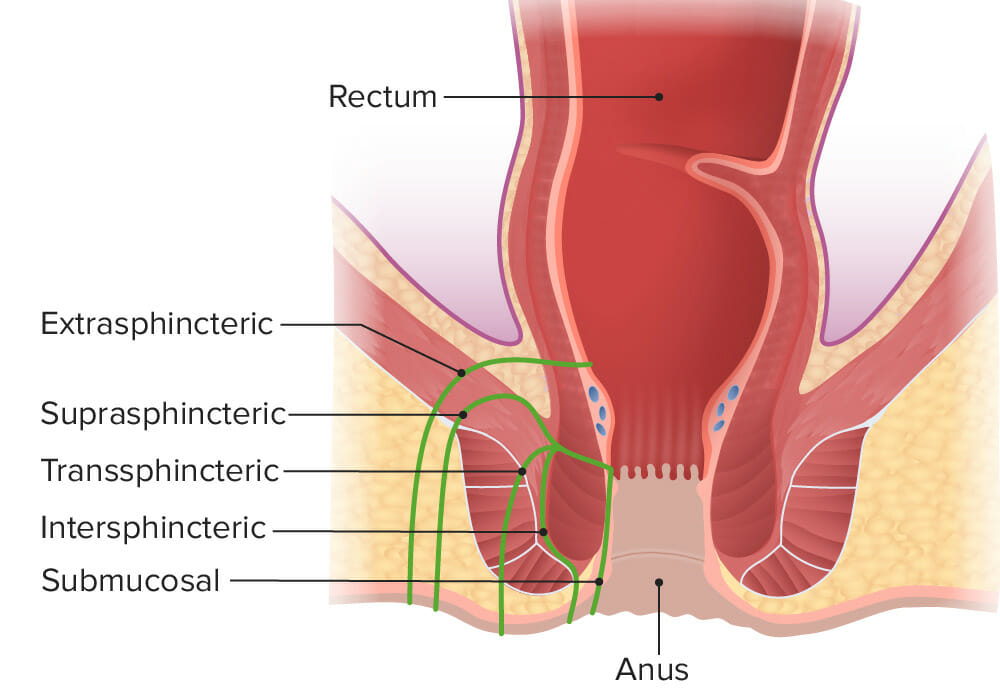

Types of fistula:

An intersphincteric (most common) fistula is located between the sphincters, which spares the external sphincter. A transsphincteric fistula goes through the internal and external sphincters, extending into the ischiorectal fossa. A suprasphincteric fistula penetrates the internal anal sphincter and tracks above the intersphincteric plane. An extrasphincteric fistula is high in the anal canal and tracks through the sphincter complex, going lateral to the sphincters before ending in the skin. A submucosal fistula does not penetrate any sphincter muscle.

General principles:[4–7]

Surgical techniques:[4–7]

Antibiotics:[7]

Why fistulas stay open: “FRIENDS”

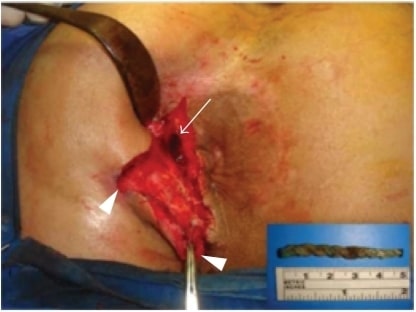

Intraoperative view of the external openings of the fistula in ano (arrowheads) and the upper part of the tract where the foreign material resided (arrow). The extracted non-absorbable braided thread is shown in the inlet figure.

Image: “Intraoperative view” by Department of General Surgery, Cerrahpasa Medical School, Istanbul University, Cerrahpasa, Fatih 34098, Istanbul, Turkey. License: CC BY 3.0Diagnosis Codes:

This code is used to diagnose an anal

fistula

Fistula

Abnormal communication most commonly seen between two internal organs, or between an internal organ and the surface of the body.

Anal Fistula (or

fistula-in-ano

Fistula-in-ano

Anal fistulas are abnormal communications between the anorectal lumen and another body structure, often to the skin. Anal fistulas often occur due to extension of anal abscesses but are also associated with specific diseases such as crohn’s disease.

Anal Fistula), an abnormal chronic tunnel that connects the anal canal to the

skin

Skin

The skin, also referred to as the integumentary system, is the largest organ of the body. The skin is primarily composed of the epidermis (outer layer) and dermis (deep layer). The epidermis is primarily composed of keratinocytes that undergo rapid turnover, while the dermis contains dense layers of connective tissue.

Skin: Structure and Functions of the buttocks.

| Coding System | Code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| ICD-10-CM | K60.3 | Anal fistula Fistula Abnormal communication most commonly seen between two internal organs, or between an internal organ and the surface of the body. Anal Fistula |

| SNOMED CT | 65863009 | Fistula-in-ano Fistula-in-ano Anal fistulas are abnormal communications between the anorectal lumen and another body structure, often to the skin. Anal fistulas often occur due to extension of anal abscesses but are also associated with specific diseases such as crohn’s disease. Anal Fistula (disorder) |

Procedures/Interventions:

These codes are for the primary surgical treatments of an anal

fistula

Fistula

Abnormal communication most commonly seen between two internal organs, or between an internal organ and the surface of the body.

Anal Fistula. A

fistulotomy

Fistulotomy

Anal Fistula involves cutting open the entire length of the

fistula

Fistula

Abnormal communication most commonly seen between two internal organs, or between an internal organ and the surface of the body.

Anal Fistula to allow it to heal from the inside out. A seton placement is used for more complex fistulas.

| Coding System | Code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CPT | 46270 | Surgical treatment of anal fistula Fistula Abnormal communication most commonly seen between two internal organs, or between an internal organ and the surface of the body. Anal Fistula (fistulectomy/ fistulotomy Fistulotomy Anal Fistula); subcutaneous |

| CPT | 46020 | Placement of seton |