An abdominal hernia is an abnormal protrusion of the abdominal contents through a weakness or defect of the abdominal wall Abdominal wall The outer margins of the abdomen, extending from the osteocartilaginous thoracic cage to the pelvis. Though its major part is muscular, the abdominal wall consists of at least seven layers: the skin, subcutaneous fat, deep fascia; abdominal muscles, transversalis fascia, extraperitoneal fat, and the parietal peritoneum. Surgical Anatomy of the Abdomen, and can be congenital Congenital Chorioretinitis or acquired. There are multiple types of hernias based on the anatomic location and the underlying pathophysiology. The most common hernias encountered in surgical practice include ventral, inguinal, and femoral hernias. Hernias are most commonly diagnosed on physical exam (abnormal bulge or protrusion), but imaging studies can sometimes be helpful for a definitive diagnosis. The management consists of surgical repair. The decision for surgery is based on patients Patients Individuals participating in the health care system for the purpose of receiving therapeutic, diagnostic, or preventive procedures. Clinician–Patient Relationship’ symptoms, their desire for surgical repair, and risks of incarceration Incarceration Inguinal Canal: Anatomy and Hernias and strangulation Strangulation Inguinal Canal: Anatomy and Hernias. Surgical options include open and laparoscopic approaches, with or without the placement of a prosthetic mesh.

Last updated: Dec 15, 2025

A hernia is an abnormal protrusion of the abdominal contents through a weakness or defect along the wall of the abdomen. Hernias can be congenital Congenital Chorioretinitis or acquired.

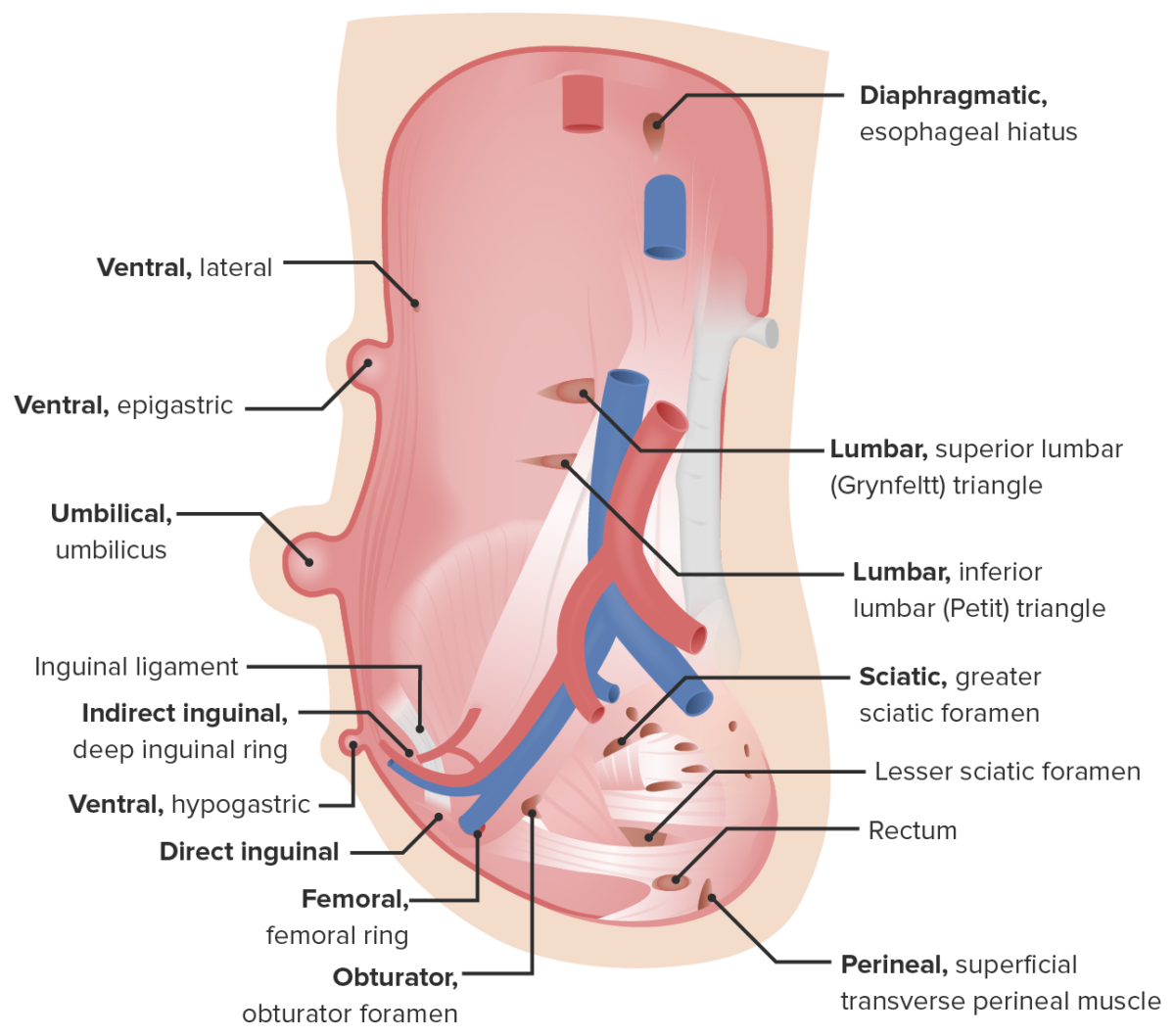

Various types of abdominal wall Abdominal wall The outer margins of the abdomen, extending from the osteocartilaginous thoracic cage to the pelvis. Though its major part is muscular, the abdominal wall consists of at least seven layers: the skin, subcutaneous fat, deep fascia; abdominal muscles, transversalis fascia, extraperitoneal fat, and the parietal peritoneum. Surgical Anatomy of the Abdomen hernias can be defined by anatomic location:

Types of hernias of the abdominal wall

Image by Lecturio.Ventral hernias occur through a weakness in the anterior abdominal wall Abdominal wall The outer margins of the abdomen, extending from the osteocartilaginous thoracic cage to the pelvis. Though its major part is muscular, the abdominal wall consists of at least seven layers: the skin, subcutaneous fat, deep fascia; abdominal muscles, transversalis fascia, extraperitoneal fat, and the parietal peritoneum. Surgical Anatomy of the Abdomen and can be congenital Congenital Chorioretinitis or acquired.

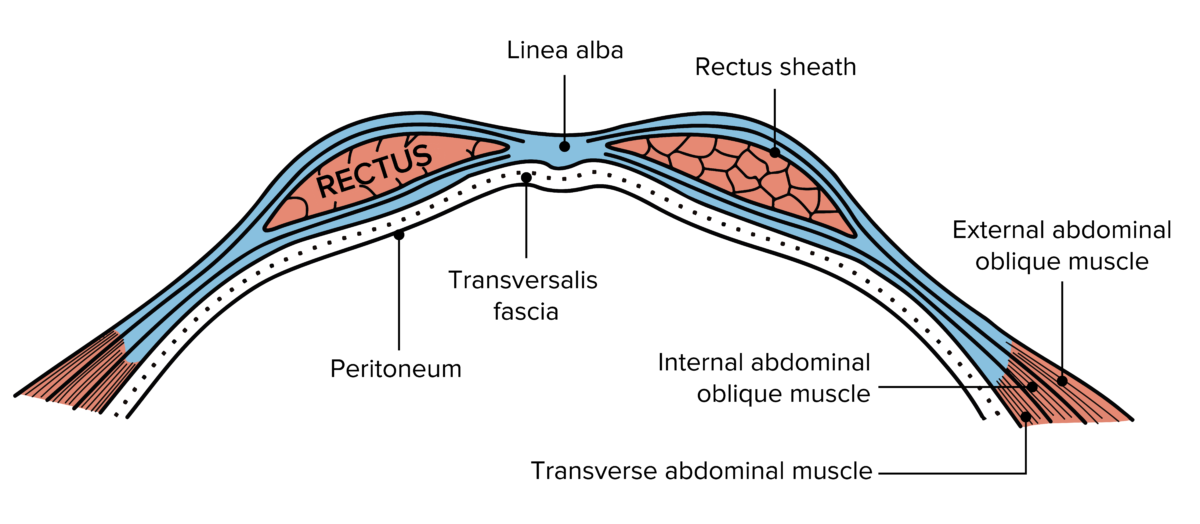

Layers of the abdominal wall Abdominal wall The outer margins of the abdomen, extending from the osteocartilaginous thoracic cage to the pelvis. Though its major part is muscular, the abdominal wall consists of at least seven layers: the skin, subcutaneous fat, deep fascia; abdominal muscles, transversalis fascia, extraperitoneal fat, and the parietal peritoneum. Surgical Anatomy of the Abdomen include:

Layers of abdominal wall

Image: “Gray399” by Henry Gray. License: Public Domain, edited by Lecturio.Epigastric hernias:

Umbilical:

Umbilical hernia in a child

Image: “Umbilical Hernia” by Jpogi (talk). License: Public DomainIncisional hernias:

Preoperative anterior view of large RUQ incisional hernia with focal areas of skin ulceration

Image: “Repair of giant subcostal hernia using porcine acellular dermal matrix (Strattice™) with bone anchors and pedicled omental flap coverage” by King J, Hayes JD, Richmond B. License: CC BY 2.0Spigelian hernias:

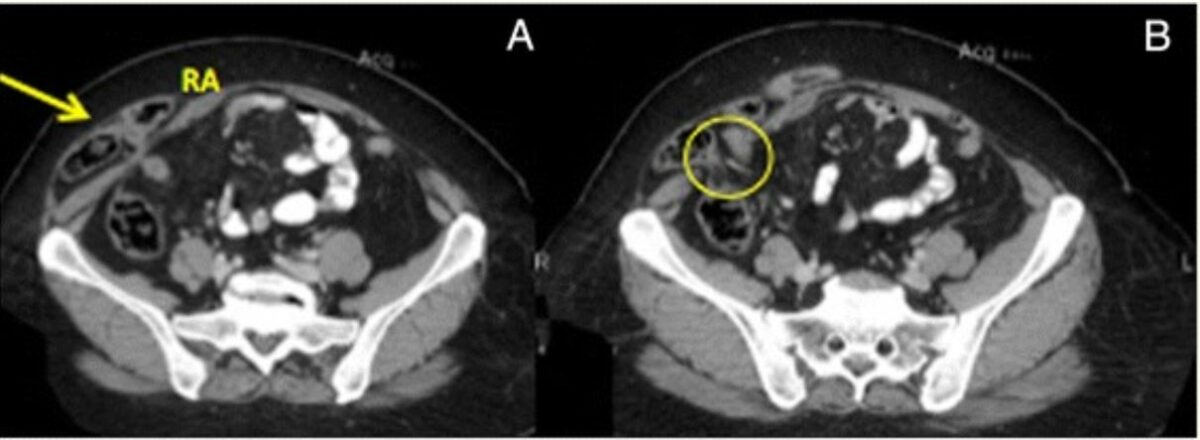

CT of right Spigelian hernia:

A: Hernia sac (arrow) containing loop of the small bowel (RA: right rectus abdominis)

B: Abdominal wall defect (circle)

Parastomal hernias:

Indications:

Primary repair:

Mesh repair:

Complications:

Inguinal hernias Inguinal Hernias An abdominal hernia with an external bulge in the groin region. It can be classified by the location of herniation. Indirect inguinal hernias occur through the internal inguinal ring. Direct inguinal hernias occur through defects in the abdominal wall (transversalis fascia) in Hesselbach’s triangle. The former type is commonly seen in children and young adults; the latter in adults. Inguinal Canal: Anatomy and Hernias occur through the floor or the internal ring of the inguinal canal Inguinal canal The tunnel in the lower anterior abdominal wall through which the spermatic cord, in the male; round ligament, in the female; nerves; and vessels pass. Its internal end is at the deep inguinal ring and its external end is at the superficial inguinal ring. Inguinal Canal: Anatomy and Hernias.

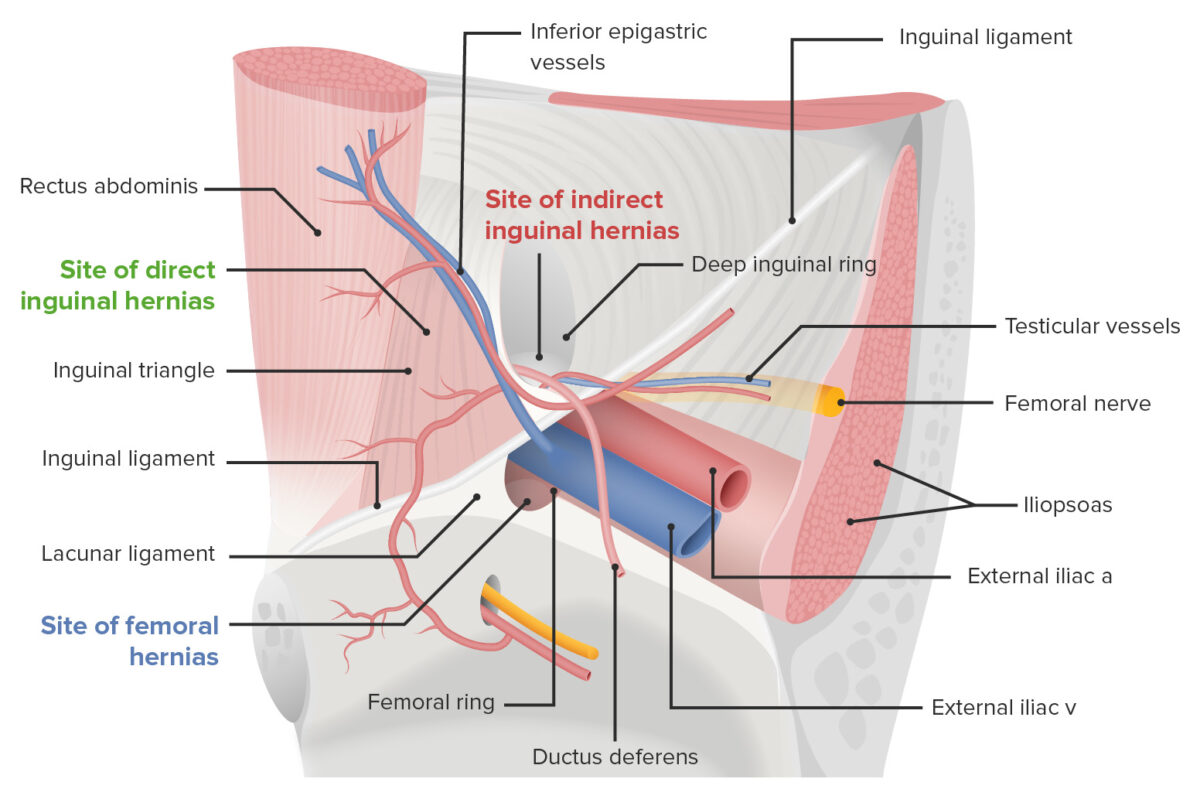

Schematic diagram showing the difference in location between direct inguinal hernias, indirect inguinal hernias, and femoral hernias:

Indirect hernias occur through the internal inguinal ring. Direct hernias occur through the external inguinal ring, medially to the epigastric vessels. Femoral hernias occur through the femoral triangle, below the inguinal (Poupart’s) ligament.

| Boundary | Level of the deep ring | Middle | Level of the superficial ring |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior wall | Internal oblique Internal oblique Muscles of the anterolateral abdominal wall consisting of the external oblique and the internal oblique muscles. The external abdominal oblique muscle fibers extend from lower thoracic ribs to the linea alba and the iliac crest. The internal abdominal oblique extend superomedially beneath the external oblique muscles. Anterior Abdominal Wall: Anatomy External oblique External oblique Muscles of the anterolateral abdominal wall consisting of the external oblique and the internal oblique muscles. The external abdominal oblique muscle fibers extend from lower thoracic ribs to the linea alba and the iliac crest. The internal abdominal oblique extend superomedially beneath the external oblique muscles. Anterior Abdominal Wall: Anatomy | External oblique External oblique Muscles of the anterolateral abdominal wall consisting of the external oblique and the internal oblique muscles. The external abdominal oblique muscle fibers extend from lower thoracic ribs to the linea alba and the iliac crest. The internal abdominal oblique extend superomedially beneath the external oblique muscles. Anterior Abdominal Wall: Anatomy aponeurosis | External oblique External oblique Muscles of the anterolateral abdominal wall consisting of the external oblique and the internal oblique muscles. The external abdominal oblique muscle fibers extend from lower thoracic ribs to the linea alba and the iliac crest. The internal abdominal oblique extend superomedially beneath the external oblique muscles. Anterior Abdominal Wall: Anatomy aponeurosis (crura) |

| Posterior wall | Transversalis fascia Fascia Layers of connective tissue of variable thickness. The superficial fascia is found immediately below the skin; the deep fascia invests muscles, nerves, and other organs. Cellulitis | Transversalis fascia Fascia Layers of connective tissue of variable thickness. The superficial fascia is found immediately below the skin; the deep fascia invests muscles, nerves, and other organs. Cellulitis | Conjoint tendon |

| Roof | Transversalis fascia Fascia Layers of connective tissue of variable thickness. The superficial fascia is found immediately below the skin; the deep fascia invests muscles, nerves, and other organs. Cellulitis | Arching fibres of internal oblique Internal oblique Muscles of the anterolateral abdominal wall consisting of the external oblique and the internal oblique muscles. The external abdominal oblique muscle fibers extend from lower thoracic ribs to the linea alba and the iliac crest. The internal abdominal oblique extend superomedially beneath the external oblique muscles. Anterior Abdominal Wall: Anatomy and transversus abdominis Transversus abdominis Anterior Abdominal Wall: Anatomy | Medial crus of external oblique |

| Floor | Inguinal ligament Inguinal Ligament Femoral Region and Hernias: Anatomy | Inguinal ligament Inguinal Ligament Femoral Region and Hernias: Anatomy | Lacunar ligament |

Anatomy of the inguinal region and hernia

Image by Lecturio.Indications:

Open approach:

Laparoscopic approach:

Complications:

Femoral hernias are hernias that occur through the femoral triangle Femoral triangle Femoral Region and Hernias: Anatomy (below the inguinal ligament Inguinal Ligament Femoral Region and Hernias: Anatomy).