Because these two conditions can have multiple etiologies, a precise diagnosis requires acquiring and interpreting multiple diagnostic tests in the correct order, which can be very confusing for medical students and physicians alike. But not to worry, here’s the system that helped me find the sweet spot (pun intended) between these two diseases for both the boards and the wards.

Step 1: Identify Cushing’s Syndrome (CS) and Adrenal Insufficiency (AI)

There are many clinical manifestations, but instead of trying to memorize everything, I want you to simply consider three broad categories:

1. Appearance/attitude

Right off the bat, patients with these two diseases will look very different when they come into the office. You will always be able to picture them perfectly if you remember that cortisol causes gluconeogenesis.

- CS → Picture a person who’s overflowing with sugar. Literally. These people will tend to have emotional lability, central obesity, atrophied muscles in the arms and legs, acne, facial plethora, stretch marks, and maybe even a Buffalo hump.

- AI → In this case, picture somebody that has run out of sugar entirely. Patients will look weak, fatigued, emotionally blunt, and poorly nurtured.

2. Labwork

Again, sugar is the key. If people have a lot of sugar, they will have “a lot” of almost everything else.

- CS → Lots of sugar means lots of stuff. High blood glucose (diabetes), high blood pressure, high lipids, high volume (edema), high bone turnover (osteoporosis), and high white blood count (but remember, CS patients are actually more susceptible to infection).

- Boards alert: Always check for CS if you have a patient with psychosis, especially if they mention new treatments recently.

- AI → No sugar? No anything else. I’m talking hypotension, hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, and low androgens, but don’t forget the exception to the rule! These patients also have hyperkalemia.

3. Function

Here’s where things get a little confusing. CS and AI patients have a loss of overlapping functions, but if you identify a patient with these dysfunctions, you can then classify them based on the other two categories.

- Loss of muscle strength.

- Loss of libido and hypogonadism

- Loss of normal pigmentation (hyperpigmentation)

Related videos

Step 2: Diagnose Cushing’s Syndrome and Adrenal Insufficiency

The hardest part of learning endocrinology is mastering the use of lab tests and substance challenges to diagnose disease once you suspect it, but all you need is to do things in the proper order. Let’s break it down:

Cushing’s syndrome

1. Exclude exogenous steroids

Before anything else happens, make sure that your patient is not using exogenous steroids (your aunt’s “special hand cream that works better than all others” almost always has hydrocortisone).

2. Establish hypercortisolism

Once you’ve excluded exogenous steroid use, establish whether the patient actually does have elevated cortisol levels. There are four main ways to do this (you just need to do one, not all of them):

- Measure late-night cortisol in saliva

- Check cortisol excretion in a 24-hour urine sample

- Perform the first of three dexamethasone suppression tests that I’ll go over in this article. Remember, everything in Endocrinology is about negative feedback. If you master this concept, everything else will make sense, and you won’t have to memorize stuff. The human body is smart, so if you give a lot of one hormone, the body will compensate by stopping the production of that same hormone so it won’t have too much. If you give steroids, the body should produce fewer steroids. The suppression test consists of administering a low dose (1 mg) of dexamethasone at night and checking the cortisol level the following morning. A healthy person’s body would respond to outside steroids by reducing its own steroids; therefore, cortisol levels would be low in the morning. If you find higher levels, that means the person has higher-than-normal cortisol. That makes sense, right?

- Perform the second of three dexamethasone suppression tests. This test shares the same concept as the first and has the same purpose. It’s just done with a higher dose and lasts two days instead of one. That’s it; no need to complicate things.

3. Find the etiology

Ok, so now that you’ve confirmed that the patient does have hypercortisolism, it’s time to determine why they have it. There are many different causes, but just focus on two categories: adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-dependent and ACTH-independent. How to find out? Just measure ACTH. I won’t complicate things; if it’s higher than 5 pg/mL, just assume it’s dependent. The next step is even easier:

ACTH-dependent means there’s some “extra” thing making ACTH (i.e., a tumor). This is where we perform the third and last suppression test. This one is high-dose but works exactly the same way as the others. If cortisol is suppressed, then the tumor is in a place “used” to ACTH, meaning a brain tumor (pituitary), and you should order an image of the head (MRI).

If cortisol isn’t suppressed, then that tumor is in a place “not used” to ACTH, meaning it’s an ectopic tumor (lung cancer or carcinoid); you should order imaging of the lung and gut (X-ray or CT).

Big board tip: Look for diarrhea and flushing. These symptoms point to a carcinoid, usually located in the appendix or the small intestine.

You can also do a corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) test. This doesn’t work with suppression. It’s even easier. CRH typically causes the pituitary to make ACTH. So if you give CRH and ACTH rises, the pituitary is the problem. If ACTH doesn’t rise, the pituitary isn’t the problem.

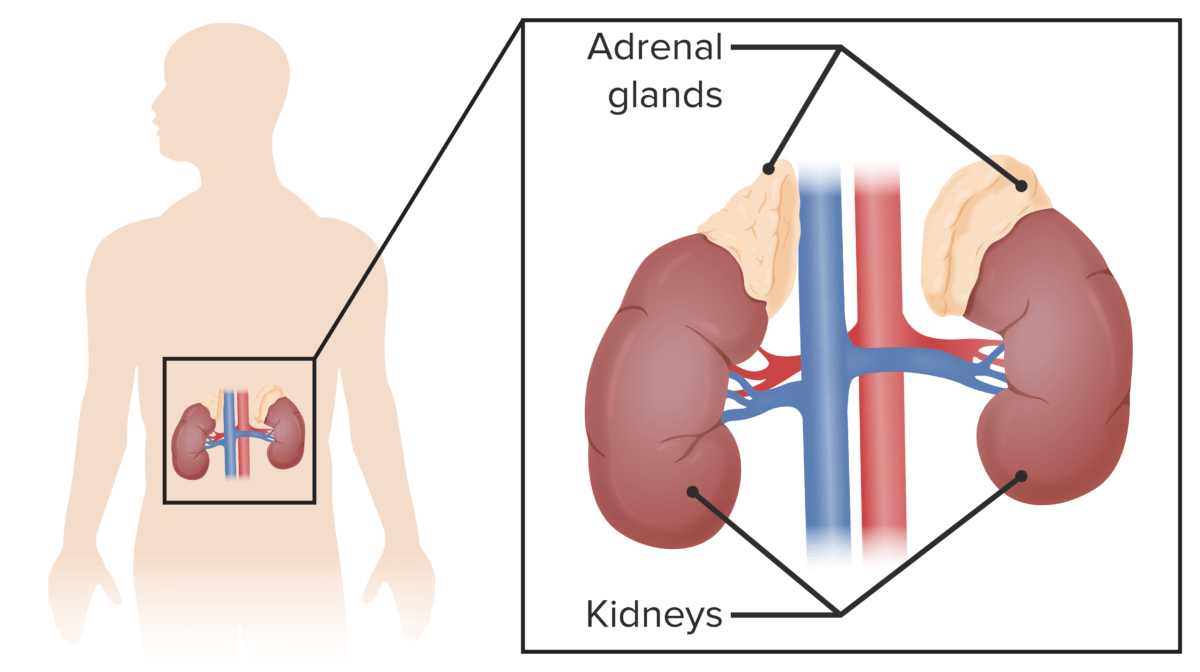

- ACTH-independent means there is no “extra” thing making ACTH, just a lot of cortisol. Where is cortisol produced? The adrenal glands. What do you have to do? Get a CT of the adrenal glands. The adrenal glands can have a tumor (making cortisol, NOT ACTH), bilateral hyperplasia, or macronodular hyperplasia.

- One more thing to consider is the infamous inferior petrosal sinus sampling. This test is rarely performed or asked about on the boards. It’s invasive, it’s expensive, and it’s dangerous. Just so you know, you only do it if the suppression tests give unclear answers or if you suspect a pituitary tumor and can’t see it on an MRI. Basically, if ACTH is a lot higher in sinus blood than peripheral blood, then that means the pituitary is pumping a lot of it, and you have a pituitary tumor.

Adrenal insufficiency

1. Establish hypocortisolism and measure ACTH

Diagnosing AI is a lot easier than diagnosing CS. You start by ordering morning serum cortisol and ACTH levels. If morning cortisol is > 18 µg/dL, then there is probably no AI. If you have < 3 µg/dL, then there is most probably AI. Anything between 3 and 18 µg/dL, you need to do an ACTH (cosyntropin) stimulation test. This test requires you to give ACTH and then measure cortisol after 30–60 min. If cortisol is low, then you have AI.

2. Find the etiology

Once you know you have AI, just check out your basal ACTH.

- If it’s high: The pituitary is working, and the problem is in the adrenal glands. Get a CT scan of the glands, and measure antibodies for autoimmune adrenalitis.

- If it’s low: The pituitary isn’t working; that’s where your problem is. Do a TSH level to work up hypopituitarism and a head MRI to rule out damage to the pituitary.

3. Some extra tips for your boards:

- “If you hear hooves, think of horses, not zebras.” Just in case that little phrase doesn’t ring a bell, it means you should always think of ordinary things first. Autoimmune is the most common cause of AI.

- Hyperpigmentation and hyperkalemia mean primary AI.

- Remember those toxic medications for AI (I’m looking at you, ketoconazole).

- Think tuberculosis, especially if the patient has risk factors.

- For some reason that I have never been able to decipher, eosinophilia is a sign of AI. The boards know that you don’t know this. So they WILL ask it. And they WILL make it look like a parasitic infection. But it’s not, so don’t take the bait.

- Always check the patient’s calcium. If it’s elevated, or if better yet, the boards mention a high level of vitamin D, remember your infiltrative granulomatous diseases. I’m talking about lymphoma and sarcoidosis.

- If there is AI with high blood sugar, look for hemochromatosis.

- If a patient with AI has hypothyroidism, remember to give steroids before you give thyroid hormones. Otherwise, you might kill your patient, which might not be a great idea.

Step 3: Treat Cushing’s Syndrome and Adrenal Insufficiency

Just some quick pointers on this:

Cushing’s syndrome

- Stop exogenous steroids (gradually).

- Adrenalectomy for adrenal hyperplasia +/- radiotherapy for cancer.

- Metyrapone and ketoconazole before adrenal surgery or if surgery is not available.

- Always give medical therapy to prepare for transsphenoidal surgery for pituitary tumors (cabergoline, mifepristone, or ketoconazole).

- Surgery +/- radiotherapy for ectopic tumors. Always think of small-cell lung cancer. Especially if you have concurrent hyponatremia.

- Remember Nelson syndrome after bilateral adrenalectomy: If there is a pituitary tumor, it will continue to enlarge because it’s still making ACTH and there are no adrenal glands for negative feedback. Think of this if the boards ask about sudden blindness shortly after surgery (apoplexy, this is an absolute emergency).

- Patients with CS have an extremely elevated risk of myocardial infarctions, thromboembolic events, and infections.

Adrenal insufficiency

- Replenish steroids using 2–3 doses daily, mimicking the circadian rhythm.

- Give a “stress dose” of steroids before you subject a patient with AI or chronic steroid use to surgery.

- Increase steroid dose in warm weather due to sodium loss during sweating.

- Monitor BP and electrolytes (especially potassium).

- Remember, women will have libido loss due to a lack of androgens. Replenish DHEA.

- Fludrocortisone to replenish mineralocorticoids for primary AI, but not secondary AI.

If faced with an adrenal crisis → Give that puppy all you’ve got ‘cause time is your enemy. Perform aggressive resuscitation with isotonic fluids, administer bolus hydrocortisone with additional doses every 6 hours, and watch for hypoglycemia.