There are a lot of organs in the abdomen. That’s why abdominal pain is such a common symptom and a very common reason for doctor visits. Many different systems are associated with the abdomen: digestive, urinary, reproductive, endocrine, exocrine, and circulatory. Often, the causes aren’t all that serious, but that doesn’t mean it should be overlooked.

In this article, I’ll talk about the differentials to abdominal pain. In real life, your differentials should already be running through your head as you take the patient’s medical history and physical exam. But don’t worry, we’ll be going through the steps on how to form your differential diagnosis step-by-step!

How to Make a Differential Diagnosis

Many diseases share similar symptoms. A patient coming in with fever and malaise can have a completely different diagnosis from another patient with the same symptoms. So how do you know how to tell which diseases your patient has? Before I get into the differentials for abdominal pain, it’s important to explain how we come up with differentials in the first place. Here are some quick steps in formulating your own:

Step 1: Collect information

History-taking and physical exams are the best way to gain information about a patient’s disease. Before a patient even talks to you, there’s a chance that you may have differentials in mind already. Watch how the patient walks, talks, dresses, or presents themselves. While patients are different in their own way, there are certain symptoms you can watch out for just by looking at the patient.

- Was the patient clutching their stomach in pain or having a hard time just walking? Were they wheeled in? This might indicate very severe pain.

- Is the patient holding a specific part of their stomach? Maybe their pain is coming from a specific location.

- Is the patient pale? Are their lips dry? Are they barely responsive? They might be dehydrated and need to be hooked for IV fluids as soon as possible.

Many students go through medical history like a checklist when they should be looking at the patients and basing their questions off what they observe as well.

Step 2: Focused physical exam

While a full body physical exam is always ideal, some patients need urgent care as soon as possible. As such, a focused PE may be more appropriate for those under time constraints. For the abdominal area, there are specific maneuvers and signs to help narrow down your choices. Murphy’s sign may be found in cases of acute cholecystitis. McBurney’s sign can indicate appendicitis. Pulsatile masses on palpation can mean an aortic aneurysm.

Take note that just because some of these tests elicit a negative response, doesn’t mean the diagnosis is totally ruled out.

Step 3: Review your differentials

Ideally, as you go through steps 1 and 2, you should already be listing differentials off the top of your head. Don’t forget to take notes so that you can review anything that you can’t recall. Basically, these are your list of suspects. You should have them checked from the most likely to least likely, or the most urgent to the least, but I’ll discuss these approaches later.

Step 4: Order tests

While many diseases can be diagnosed clinically (that is, through history-taking and physical exam), you should still run tests to confirm the diagnosis. These tests can include a urinalysis, fecalysis, complete blood counts, blood chemistry, and other diagnostics. Of course, you have to ensure that your patient is stable and all the emergent problems are addressed as much as possible before running tests.

Types of Abdominal Pain

One of the first things you should do is to characterize the pain the patient feels. For most chief complaints, we use the mnemonic OLD CARTS. These letters stand for:

- Onset: How long has the pain been ongoing? Is it acute or chronic?

- Location: Where did the pain start? Did it radiate anywhere else?

- Duration: When the pain happens, how long does it last?

- Character: What type of pain is it? Is it dull, burning, sharp, etc.?

- Aggravating factors: Does the pain worsen with any triggers?

- Relieving factors: Does the pain improve when you do something like take medications or go into a specific position?

- Timing: Is the pain constant or intermittent? Does it occur at certain times of the day or after meals?

- Severity: On a scale of 1 to 10, how would you rate your pain?

After characterizing the pain, you can narrow down possible diagnoses. Some people also use OPQRST, which asks almost the same questions, but for the purposes of this article, we’ll stick with OLD CARTS.

Acute vs chronic abdominal pain

Acute pain means the onset was sudden and usually started shortly before consult. Chronic means the pain may have gone on for weeks, months, and even years. Acute abdominal pain is very broad, but many medical emergencies are associated with acute, severe abdominal pain.

Some acute diseases include, cholecystitis, appendicitis, pancreatitis, etc. Meanwhile, some chronic diseases can include diverticulitis, GERD, irritable bowel syndrome, and many others.

Qualities of pain: cramping, dull, aching, sharp, or burning

Next, let’s talk about the different qualities of pain. Patients may describe their pain as crampy or sharp. Some may say they feel like they’re being punched in the gut or stabbed in a specific area.

For example, a burning sensation would point to a peptic ulcer. Cramping pain in women could be a case of dysmenorrhea. Cramping pain can also be associated with acute gastroenteritis. Since many diagnoses share types of pain, characterizing isn’t enough– you need to complete the OLD CARTS checklist as much as possible.

Constant or intermittent

Constant pain means that the pain is always there while intermittent pain means that the pain comes and goes. If the pain is chronic, it’s usually intermittent. However, there can be cases where the pain is constant like in chronic pancreatitis, malignancies, and somatoform disorders.

For intermittent pain, it’s important to investigate possible patterns as to when the pain comes back. For example gallstones can cause intermittent pain which comes after eating fatty foods.

Approaches to Abdominal Pain

Next, let’s talk about your approach. When you hear “abdominal pain”, you should have a short list of diseases that you want to rule out first. After your history-taking and physical exam, you should have narrowed down your list a bit more. Then, you can run the patient through diagnostic tests.

It is recommended that you incorporate all these approaches because they can narrow down your differentials and you can address life-threatening diseases early. Make sure that the patient gets the right care immediately and minimize their expenses on diagnostic tests, if possible.

Local anatomic approach

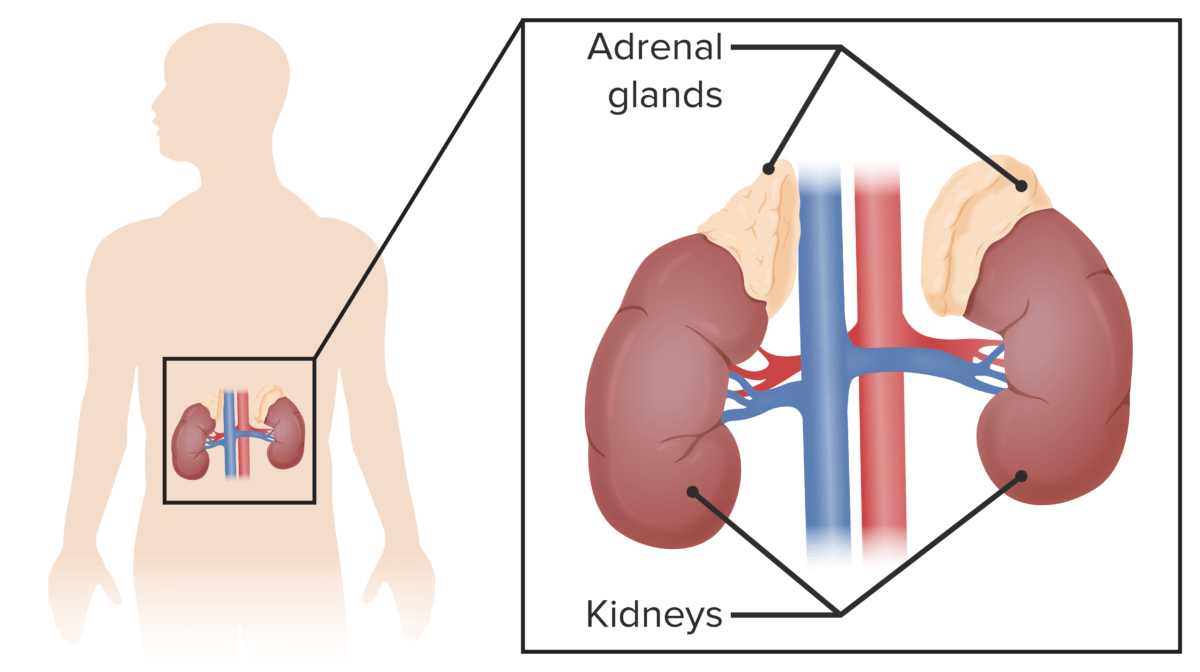

This approach involves using the location of the pain to narrow down your differentials. To do this, you must visualize where the different organs of the abdomen are located. For example, the uterus and bladder are found on the lower/hypogastric part of the abdomen. The spleen is in the upper left abdomen, just under the ribcage. The stomach is in the upper/epigastric portion of the abdomen. As the patient describes where the pain is, start considering possible organs that could be involved.

However, this approach can be faulty because different diseases can cause radiating pain or referred pain. Take note that these are two separate concepts. Radiating pain is when the pain travels from one part of the body to another. Referred pain is when the pain is felt somewhere other than the original site of pain.

For example, pancreatitis can exhibit as epigastric or central pain that radiates to the back. There is also generalized pain, where pain is diffused around the abdomen or the patient can’t pinpoint the exact location of the pain. Here are some examples:

| Location of pain | Possible diagnoses |

| Generalized/diffuse | Aortic aneurysm rupture Ectopic pregnancy Perforation of abdominal organs Aortic dissection |

| Central/periumbilical area | Acute small bowel ischemia Small bowel obstruction |

| Epigastric area | Gastritis Peptic ulcer disease/dyspepsiaIrritable bowel syndrome Esophageal rupture/Boerhaave syndrome Myocardial infarction |

| Right upper quadrant/hypochondrium | Hepatitis Hepatomegaly Cholecystitis Cholelithiasis |

| Left upper quadrant/hypochondrium | Ruptured spleen Acute pyelonephritis Aneurysm of splenic artery Gastric distension Subphrenic abscess |

| Right lower quadrant/iliac fossa | Appendicitis Crohn’s disease Meckel diverticulum Constipation Ectopic pregnancy Pelvic inflammatory disease Seminal vesiculitis Undescended testicle pathology UTI |

| Left lower quadrant/iliac fossa | Diverticulitis Constipation Ectopic pregnancy Pelvic inflammatory disease Seminal vesiculitis Undescended testicle pathology UTI |

| Suprapubic | Urinary retention Cystitis Menstrual cramps/dysmenorrhea |

| Loin | Pyelonephritis Renal colic Renal vein thrombosis Retroperitoneal hemorrhage or infection |

| Groin | Renal stones Testicular torsion Epididymo-orchitis Hip or pelvic fracture/injury |

As you can see, there are some differentials that aren’t related to the gastrointestinal system. It can involve the reproductive, urinary, circulatory, and even cardiac system. Note that while there are specific diseases associated with the left and right areas, don’t forget that there are organs that can present with pain on either side like the kidneys and ovaries.

Most common

For this approach, we have to consider the demographic of the patient. Are they young or old? Are they of reproductive age? Are they male? It’s not enough to know where the pain is from. Consider what would be the most likely cause for your patient, based on their characteristics.

For women of reproductive age, abdominal pain is an indication to test for a possible pregnancy. Abdominal pain is also common in women as it is often caused by regular period cramps but you could also consider endometriosis. For men, seminal vesiculitis or epididymitis can present as abdominal pain. For older patients, especially post-menopausal women, hip fractures are common following a simple injury. For the general population, however, abdominal pain is most commonly caused by gas or infections like acute gastroenteritis.

The acute abdomen and urgent cases

This approach is most appropriate if you work in an emergency room. There are many causes of abdominal pain that need intervention as soon as possible. Because there are so many differentials, you need to do your clinical assessment quickly so that you can rule out some of the most life-threatening ones as soon as possible.

For these cases, we call them an acute abdomen. This means that the condition needs urgent intervention. It is marked by the acute onset of severe abdominal pain. Common cases of these are acute appendicitis, cholecystitis, pancreatitis, and diverticulitis. In newborns, it can be necrotizing enterocolitis. In younger children, it can be volvulus or intussusception. But the most common cause in kids is appendicitis.

Some warning signs that will definitely need intervention as soon as possible are patients presenting with:

- Acute bleeding: The most serious cause of this is an aortic aneurysm, but it can also mean an ectopic pregnancy, bleeding ulcers, or a traumatic injury for those with a recent history of accidents. This can cause patients to go into hypovolemic shock, eventually leading to death if not addressed.

- Perforated viscus: This is usually caused by peptic ulcer disease, bowel obstruction that was untreated, diverticular diseases, and inflammatory bowel disease. Localized perforations can present with more localized pain and patients can still look generally well. Meanwhile, generalized peritonitis can present with more diffuse pain, abdominal rigidity, and patients look extremely unwell.

- Ischemic bowel: Patients with abdominal pain described as “severely out of proportion” should be assumed to have ischemic bowel until proven otherwise. This happens when there is an occlusion of mesenteric vessels, stopping the blood supply to a part of the bowels.

There are also mimickers of abdominal pain. These “mimics” mean that while the patient is experiencing abdominal pain, the urgent cause may not be gastrointestinal in nature. Life-threatening diagnoses include acute coronary syndrome, aortic dissections or aneurysms, pulmonary embolisms, ectopic pregnancy, testicular or ovarian torsion, hyperglycemic emergencies such as diabetic ketoacidosis, and adrenal crisis. So while the patient is experiencing abdominal pain, hooking them up to a heart monitor or testing them for their blood sugar levels is not out of the question.

Mnemonic for acute abdominal cases

Many students use the mnemonic ABDOMINAL for acute cases. This stands for:

- Appendicitis

- Biliary tract disease (such as cholecystitis)

- Diverticulitis

- Ovarian disease

- Malignancy

- Intestinal obstruction

- Nephritis disorders

- Acute pancreatitis

- Liquor (ethanol)